South America boasts a long coastline on both the east and west sides, primarily featuring two countries along the western coast bordering the Pacific Ocean: Peru to the north and Chile to the south. The coastal deserts of Peru are also where archaeologists have discovered the Pisco Formation, a geological layer formed approximately 15 million to 2 million years ago. This formation has yielded numerous bizarre fossils, including a particularly strange species of marine mammal.

The fossils of this unique marine mammal were first discovered in the 1990s. According to initial assessments by paleontologists, this creature belongs to the giant ground sloth family – Megatheriidae, with Megatherium being the most famous species. In 1995, paleontologists named this ancient creature Thalassocnus, commonly referred to as the marine sloth.

After the marine sloth was named, paleontologists uncovered many more fossils of this creature in Chile and southern Peru. To date, a total of 5 species of marine sloths have been identified.

Location of marine sloth fossil discovery in South America.

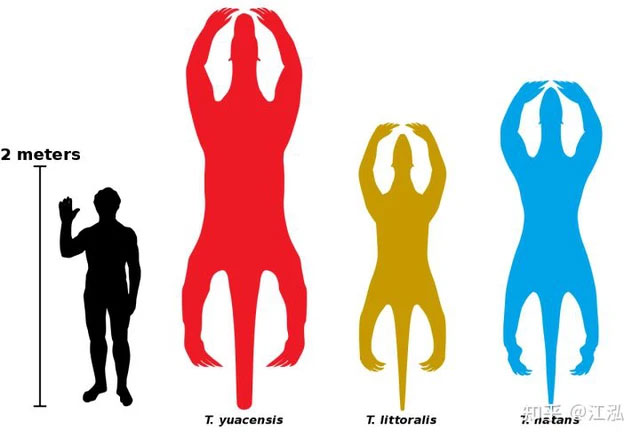

The size of the marine sloth is significantly larger than that of modern sloths, with the smallest species measuring over 2 meters long and the largest reaching up to 3.3 meters.

Size comparison between marine sloths and humans.

The marine sloth has a long head and a flexible upper lip at the front of its upper jaw, enabling it to tear food and bring it to its mouth. Inside the mouth, there are two rows of strong teeth, which indicate that they were solely used for chewing plants, confirming that marine sloths were typical herbivores. In comparison to their heads, the bodies of marine sloths were relatively robust and quite heavy, making them well-suited for diving.

Reconstruction of the marine sloth skull.

The limbs of the marine sloth were long and powerful, equipped with large, curved claws that could serve as defensive weapons. Fossil analyses suggest that this animal moved very slowly on land; however, the story was entirely different underwater, where they were extremely agile.

Thalassocnus is an extinct genus of semi-aquatic ground sloths from the Miocene and Pliocene of the Pacific coast of South America. It is a monotypic genus in the subfamily Thalassocninae.

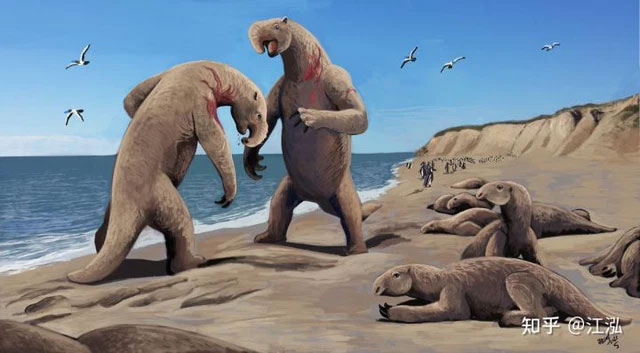

As mentioned earlier, the marine sloth was herbivorous, feeding on seaweed and flowering plants growing on the ocean floor. Marine sloths typically rested on the beach and only ventured into the sea when foraging for food. Compared to their ancestors, marine sloths exhibited a 20% increase in bone weight, which facilitated longer diving durations.

Marine sloth is an herbivorous animal.

They are the only known aquatic sloths. Thalassocninae is a remarkable group because they are classified within both the Megatheriidae and Nothrotheriidae families.

Underwater, marine sloths not only swam using their limbs but also propelled their bodies forward by waving their flat tails. Upon reaching the ocean floor, the powerful limbs of the marine sloth acted as an “anchor.” Despite their ability to cling to the seabed, marine sloths could still be swept away by strong waves and sometimes fell victim to heavy underwater rocks, as evidenced by the numerous fossils found with breakage marks from impacts.

For marine sloths, strong winds and waves are not a real danger.

Thalassocnus evolved several adaptations for life in the sea over 4 million years, such as thick and heavy bones to counter buoyancy, nostrils that migrated further forward to facilitate breathing while fully submerged, broader and longer snouts for better consumption of aquatic plants, and heads angled further downward to assist with bottom feeding. Their long tails were likely used for diving and maintaining balance, similar to modern beavers.

However, for marine sloths, strong winds and waves were not the real danger; instead, terrifying threats lurked in the ocean while they foraged. Numerous fierce predators roamed the prehistoric waters off the western coast of South America, including many ancient shark species and toothed whales, most notably the Acrophyseter sperm whale. Although Acrophyseter was not large, they traveled in packs and possessed two rows of thick teeth, seemingly designed specifically for hunting sloths.

Acrophyseter sperm whale hunting marine sloths.

The extinction of marine sloths did not primarily stem from predators; rather, it began with a significant geological event. Approximately 3 million years ago, the ocean between North and South America closed, linking the two continents. This event caused the warm ocean currents flowing from the Caribbean Sea to the western coast of South America to vanish, leading to a decline in ocean temperatures. Consequently, marine plants could no longer thrive, resulting in a food crisis for the marine sloths. Simultaneously, the sloths lacked a layer of fat on their bodies, making them unable to withstand the dropping temperatures and freezing waters, turning their foraging expeditions into torturous experiences.

It was this crisis caused by the decline in ocean temperatures that ultimately led to the extinction of marine sloths 3 million years ago. Marine sloths first appeared 7 million years ago, and after 4 million years, they completely vanished due to environmental changes.