Sixteen years before Alexander Fleming discovered the antibiotic that inhibits bacteria in mold, a French scientist also described a similar finding in his thesis.

In 1897, a young French medical student named Ernest Duchesne submitted a doctoral dissertation titled Contributions to the study of the competitive struggle for existence among microorganisms: The antagonism between mold and bacteria. In this dissertation, Duchesne proposed a revolutionary idea that bacteria and mold are engaged in a constant struggle for survival and that humans can exploit this antagonism to treat diseases, according to Amusing Planet.

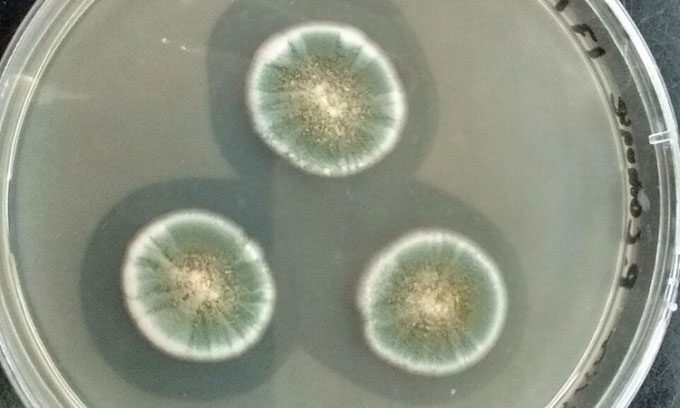

Petri dish of Penicillium glaucum mold. (Photo: Wikipedia).

Although the medicinal properties of fungi and plants in treating infectious diseases have been known since ancient times, Duchesne was the first to experimentally demonstrate that certain molds destroy pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella typhi (causing typhoid fever) and Escherichia coli in laboratory settings when injected into guinea pigs. What Duchesne discovered was the natural antibiotic penicillin, a breakthrough often associated with the Scottish physician Alexander Fleming. Duchesne’s research was nearly forgotten until it was rediscovered more than 50 years later, in 1949, four years after Fleming was awarded the Nobel Prize.

Ernest Duchesne was born in Paris in 1874, the son of a chemical engineer who owned a tannery. After completing high school, he enrolled in the military medical school in Lyon (École du Service de Santé Militaire) in 1894. Two years later, Duchesne began his research under the guidance of Gabriel Roux, a professor of microbiology and director of the provincial health agency in Lyon.

Roux observed an interesting phenomenon. Although mold spores were abundant in the air, they were absent in water flowing from taps and fountains, even though they could grow in distilled water. This led Roux to suspect that some microorganisms in the water might inhibit the growth of mold. He suggested that Duchesne explore this idea as the basis for his dissertation. This observation marked the beginning of Duchesne’s core research on competition with bacteria, ultimately leading to his penicillin discovery.

Duchesne conducted a series of experiments in which he cultured Penicillium glaucum in meat broth and then introduced small amounts of Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli into the mold population. Each time, the mold spores died. He concluded that in the struggle for survival, bacteria held the upper hand. However, Duchesne speculated that before Penicillium died, it could weaken bacteria, thereby reducing their virulence and pathogenic properties.

To test this hypothesis, Duchesne injected guinea pigs with a solution containing equal amounts of Penicillium glaucum and E. coli. Initially, the guinea pigs were severely ill, but they quickly recovered. Two days after the first injection, he administered a similar dose. The experimental animals showed no signs of illness, proving they had developed resistance to E. coli. When he injected a mixture of S. typhi and P. glaucum into the guinea pigs, they also exhibited a similar immune response.

Duchesne found that the mold (Penicillium glaucum), injected into animals simultaneously with certain bacteria like S. typhi and E. coli, could significantly reduce their virulence. Although Duchesne could not identify the antibiotic produced by Penicillium glaucum, he correctly concluded how to use mold to treat diseases.

His dissertation earned him a doctorate, but his ideas did not attract the medical community. By the end of 1898, Duchesne was appointed as a physician in the second cavalry regiment stationed in Senlis. He married in 1901, but his wife died two years later from tuberculosis. He himself fell ill in 1904 and retired in 1907. He spent his later years in various nursing homes in southern France and Switzerland before passing away in 1912 at the age of 37.

In 1928, sixteen years later, Alexander Fleming made a similar discovery when his Staphylococcus aureus culture accidentally contaminated with Penicillium mold. Like Duchesne, Fleming observed that the mold released a compound that inhibited bacterial growth. Despite the significant implications of the discovery, Fleming’s published paper in the British journal Experimental Pathology did not attract much attention, similar to Duchesne’s dissertation many years earlier.

Fleming himself was uncertain about the practical medical applications of his discovery. He focused more on potential applications in isolating bacteria rather than treating infectious diseases. His fellow chemists tried to isolate the active compound penicillin but were unsuccessful, leading Fleming to halt further research.

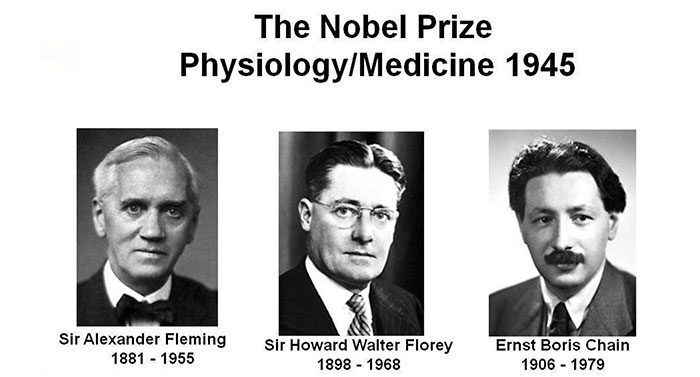

Three scientists awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 for discovering antibiotics.

A decade later, in the late 1930s, British biochemist Ernst Boris Chain rediscovered Fleming’s overlooked 1929 paper. Recognizing its potential, Chain suggested to Australian scientist Howard Florey to explore the antibacterial compounds released by microorganisms. Florey assembled a team of biologists and biochemists at the University of Oxford. Their collaborative efforts ultimately succeeded in isolating and mass-producing penicillin, turning it into a life-saving antibacterial agent. This breakthrough came just in time for widespread use during World War II, transforming medicine.

After the therapeutic properties of penicillin became widely recognized, Alexander Fleming became the center of attention, even overshadowing Howard Florey. In 1945, Fleming, along with Florey and Ernst Boris Chain, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in many infectious diseases.” Although the award was shared equally among the three, Fleming continued to receive public recognition, while the crucial roles of Florey and Chain in developing penicillin into a viable treatment were often downplayed.