While the city-states of Greece thrived, China was also in a period of intense competition for dominance among its princes.

Among the hundreds of city-states in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta were always the most powerful entities. The naval strength of Athens far surpassed that of other city-states, while Sparta excelled with its formidable army. Despite the immense power of these two city-states, they were unable to unify the Greek peninsula.

Why Didn’t Athens and Sparta Conquer Other States and Unify the Greek Peninsula?

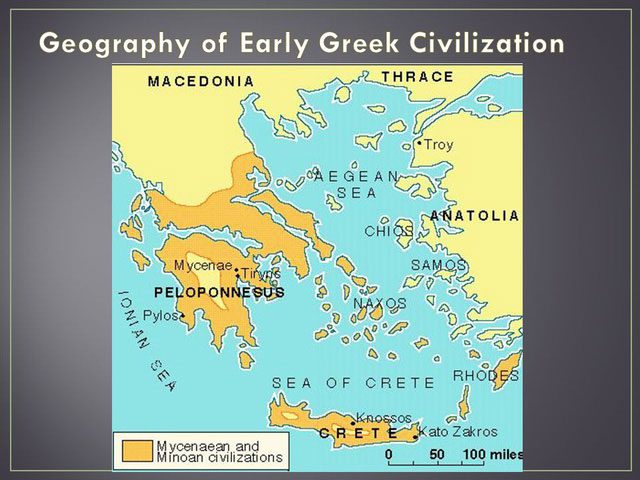

Throughout the development of human civilization, many cultures emerged from large river systems—these are known as river valley civilizations. However, ancient Greek civilization was distinct from these; it belonged to a maritime civilization.

The geography of the Greek Peninsula is incredibly complex, with 80% mountainous terrain and only 20% flat land, which is generally arid and not conducive to agricultural development. Such natural conditions hindered the formation of a cohesive civilization.

However, the Greek Peninsula is bordered by the sea on three sides and contains many islands, facilitating maritime transport. The ancient Greeks, leveraging their advanced maritime technology, considered the Mediterranean Sea their primary operational area. They sailed south across the Mediterranean to ancient Egypt, where one of the earliest human civilizations thrived, and eastward to the sphere of influence of Babylonian civilization.

Through trade and maritime exchange, the ancient Greeks absorbed the achievements of these two great civilizations. Around the 20th century BCE, ancient Greek civilization began on the island of Crete in the Mediterranean.

Numerous mountain ranges and rivers cut through the Greek Peninsula, dividing it into relatively isolated plains. The rugged terrain made transportation across the peninsula very inconvenient, limiting communication among the people, while the myriad islands in the Mediterranean favored the development of overseas trade.

Colonies of ancient Greece.

Influenced by these unique natural conditions, hundreds of large and small city-states emerged on the Greek Peninsula in the 8th century BCE. These city-states typically focused around a central town and were surrounded by rural areas, covering small territories. Most city-states ranged from 50 to 100 square kilometers in size.

The city-states varied in scale and population. Most contained only a few thousand people. Among these small city-states were two giants: Athens and Sparta. Athens covered over 2,000 square kilometers, while Sparta spanned 8,400 square kilometers, both boasting populations in the hundreds of thousands.

Ancient Greek city-states commonly employed iron tools in agriculture, which significantly increased food production. The small-scale, subsistence farming model met the needs of the city-state, described as “small states with few people.”

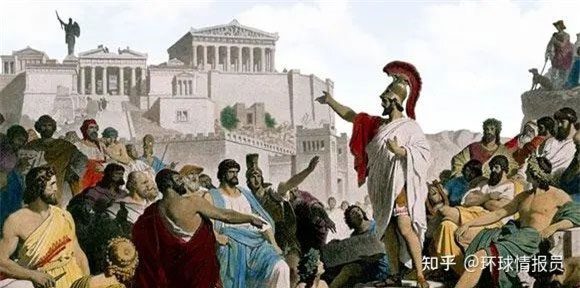

Moreover, through reforms, the city-states granted citizens certain rights, such as voting rights and the right for citizens of Athens to be elected. This recognition of citizenship enhanced individual citizens’ ties to their city-states.

City-states granted citizens some rights.

In the eyes of the ancient Greeks, they placed immense importance on kinship; each Greek city-state had its own patron deity, such as Athena for Athens.

Not only did the states have different beliefs, but their currencies and measurement systems were also inconsistent. Coupled with the fact that many city-states were focused on foreign trade, there was little exchange between them. Although they spoke the same language, they could not reach a consensus among “those of the same ethnicity.”

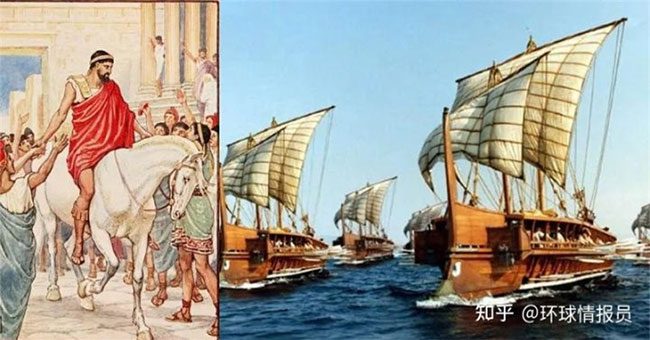

Among the hundreds of city-states in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta held absolute dominance. Despite Athens being mountainous with limited land, its proximity to the Aegean Sea in the south and east was advantageous for maritime trade. To maintain overseas commerce, Athens developed its naval forces robustly, far exceeding those of other city-states.

The growth of commodity economy and foreign trade led to relative prosperity among Athenians. Athens’ democratic system also fostered a spirit of openness and freedom, elements that contributed to the flourishing culture of Athens, making it a cultural center of ancient Greece.

However, naval power could not compensate for the limitations imposed by economic policies. The emphasis on foreign trade severed economic ties with other cities on the peninsula. This flaw significantly hampered Athens’ efforts to unify the city-states. Additionally, the Athenian military was not strong enough to achieve unification of the peninsula.

The Athenian army was not strong enough to unify the peninsula.

The situation in Sparta contrasted sharply with that of Athens. Located at the southern tip of the peninsula and near the sea, Sparta prioritized military training. Spartan boys underwent rigorous military training from a young age, becoming full-fledged soldiers at just 20 years old. With this strict military training, Sparta established a powerful army that dominated southern Greece for many years.

Sparta also formed a military alliance in 546 BCE, although it was somewhat loose. Despite being one of the largest and most populous states among all city-states, it did not harbor ambitions to unify the Greek peninsula.

Within the alliance, while Sparta could convene meetings of all member states and serve as the commander-in-chief of allied forces in war, the states within the alliance maintained their own internal issues and had equal voting rights on matters of peace and war affecting the entire alliance. They adhered to the principle of minority obeying the majority. Due to its long-standing military focus, Sparta’s culture, education, and economy were relatively backward, making it difficult to influence other city-states. The inherent flaws of both Athens and Sparta, along with the disunity among the city-states, rendered the path to unifying ancient Greece exceedingly difficult.

The ancient Greeks revered city-state freedom and opposed imperialist ideology.

The ancient Greeks cherished city-state autonomy and opposed imperialist ideology. In the eyes of citizens from various states, the independence of their city was paramount. The fervor for independence and freedom among the city-states led the people to strongly resent outsiders, even viewing those from outside their city as enemies.

Thus, despite sharing the same ethnicity and language, they could not form a unified nation.

It may be that living in peace led Athens and Sparta to not realize that many city-states were indeed part of the same nation, lacking a sense of unity for Greece; however, when the foreign Persians invaded, they failed to evoke the ancient Greeks’ call for unity.

As the city-state system of Greece flourished, a massive empire—Persia—emerged in the east. The Persians established the Persian dynasty in 550 BCE and launched successive wars of invasion against the Greek city-states. In 490 BCE, Darius I of Persia sent an army to attack the Greek city-states once again.

The Persians established the Persian dynasty in 550 BCE.

The Persian soldiers were divided into two groups, crossing the Turkish strait to conquer Thrace and Macedonia from north to south; another group attacked westward, conquering the Ionian region (now the southwestern coast of Turkey).

The Greek city-states invaded by Persia eventually realized that they shared a common language and ethnicity, recognizing that the Persians were the true foreigners. Therefore, they turned to Athens and Sparta for help.

Map of the Persian invasion route.

Sparta believed that the Persian invasion did not pose a threat to them. Furthermore, Sparta was attempting to find a way to ensure that both Athens and Persia would suffer defeats while reaping benefits for themselves, which is why they chose not to engage in this conflict.

Athens sent troops to support the invaded nations. In 490 BC, the Persian army and Athenian forces clashed at the Marathon Plain, where Athens ultimately defeated 6,400 Persian soldiers at the cost of 192 of their own. After the war, Persia chose to withdraw due to internal instability. This victory significantly enhanced Athens’ prestige and political influence among the city-states.

Though Persia temporarily withdrew, it did not abandon its plans to conquer Greece. Ten years later, they dispatched an additional 300,000 troops and 1,000 warships to invade. In this campaign, the Persian army was unprecedentedly strong, and the Greek states felt a serious threat.

To maintain the independence and freedom of their city-state, Athens and Sparta united to form an alliance against Persia. The two powers combined their strengths, naval and land forces, becoming the backbone of the resistance against Persia. In the battle at Thermopylae, 300 Spartans sacrificed their lives to inflict nearly 20,000 casualties on the Persians.

The Athenian navy exploited the maneuverability of their warships to deal heavy damage to the Persian navy, resulting in the destruction of most of their vessels. Consequently, Persia was forced to withdraw from the Greek peninsula. The Greek city-states emerged victorious in the Second Greco-Persian War.

The Greco-Persian Wars exemplify the cooperation between Athens and Sparta, marking an unprecedented period of collaboration among the Greek city-states. Although the war made the Greek nations realize their shared ethnicity, the demands for freedom and independence of the city-states overshadowed their understanding of unity.

Therefore, after triumphing over external threats, the city-states adhered to the principle of “city-state above all”. In defense of their independence and sovereignty, they resolutely opposed hegemony and imperialist ideologies, which ultimately led to internal strife.

The power and exploitation of Athens led to dissatisfaction among other cities.

The Greek city-states managed to repel the Persian invasion, but they did not eliminate the Persian threat entirely. To continue the fight against Persia, in 478 BC, over 150 city-states in northern Greece formed the Delian League.

Thanks to its strong influence, Athens compelled the member states of the league to become its vassals. Athens transferred the league’s treasury to its own territory, severely repressing cities that declared their withdrawal from the alliance, and demanded that allied states use Athenian currency, among other measures. The Delian League effectively became Athens’ own possession, marking the initial formation of the “Athenian Empire.”

The power and exploitation of Athens led to discontent among other cities. The conflict between Athens’ imperialist ideology and the city-state ideology led by Sparta eventually escalated into a full-blown war among the Greek city-states.

In 450 BC, a prolonged conflict occurred between the city-states led by Athens and Sparta, known in history as the “Peloponnesian War.” Neither side could decisively defeat the other, leading to a peace negotiation.

However, this period of peace was short-lived, and war erupted again between Athens and Sparta in 431 BC. At the war’s outset, Athens and its allies leveraged their naval superiority to attack Sparta, while Sparta and its allies utilized their land forces to resist. The advantages and challenges for both sides were evident, resulting in a stalemate after years of inconclusive warfare.

In 412 BC, Persia officially intervened in the conflict, actively supporting Sparta in developing its navy. The Spartan navy defeated the Athenian navy in 405 BC at the Hellespont. Of the 170 Athenian warships involved, only 9 remained intact.

Persia actively supported Sparta in developing its navy.

In 404 BC, Athens was defeated and forced to dissolve the Delian League. Athens and its allied city-states accepted Sparta’s leadership, making Sparta the dominant power throughout Greece.

After the war, the Spartans collected tribute from the cities of the Delian League and established a new political regime to replace democracy. Sparta’s policies once again led to continuous wars in Greece, severely weakening the strength of the Greek city-states.

Amid ongoing internal conflicts in Greece and the weakening of its power, Persia, which benefited from these wars, played the role of mediator and arbitrator. In 387 BC, the city-states signed an agreement at Persia’s request. The agreement not only ensured that all Greek cities enjoyed autonomy but also stipulated that if a city-state went to war, Persia could intervene.

All Greek nations accepted Persia’s arbitration. This reconciliation declared that the city-state standard had triumphed over the imperial unification idea, with Athens and Sparta completely withdrawing from the mission of unifying Greece.

Ultimately, the heavy responsibility of unifying Greece fell upon the shoulders of the Macedonians in the north. The Macedonians had long been on the fringes of Greek culture, economically and culturally relatively backward, and were referred to by the Greeks as “barbarians.” Macedonia took advantage of the decline of city-states like Athens and Sparta to adopt the superior Greek culture and began the process of “Hellenization.”

Under the leadership of Alexander the Great, after Macedonia unified Greece in 337 BC, Alexander continued to expand abroad. After 10 years of military campaigns, he established a vast empire spanning three continents: Asia, Europe, and Africa.