Composer Beethoven Continued to Create Masterpieces Even When He Could No Longer Hear Until the End of His Life.

The German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) is considered one of the greatest musicians in history. From a very young age, he displayed his genius and was regarded as the most famous composer since Mozart. However, at the age of 30, Beethoven faced an unimaginable challenge for a musician: he became deaf.

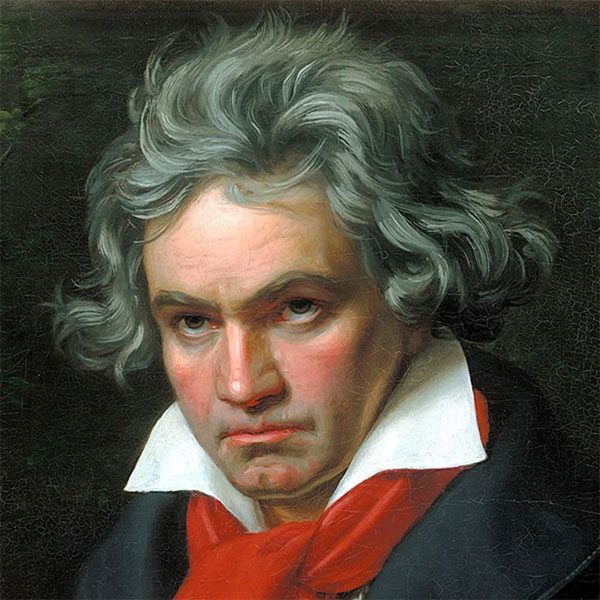

Painting of Beethoven – the great composer with immortal works famous even to this day

What Caused Beethoven’s Deafness?

Around the age of 26, Beethoven began to experience persistent buzzing and ringing in his ears. In 1800, at the age of 30, he wrote a letter from Vienna to a childhood friend, sharing: “For the past three years, my hearing has been gradually weakening. In the theater, I have to get very close to the orchestra to hear the performers. I cannot hear the high notes of the instruments or the singer’s voice.”

As a musician, Beethoven tried to keep his condition a secret from even his closest friends, fearing that his career would be ruined if anyone found out. He avoided social interactions to prevent revealing his illness, and he was also afraid to face it himself.

It is believed that Beethoven could still hear some speech and music until 1812. However, by the age of 44, he was nearly completely deaf.

The exact cause of the talented composer’s hearing loss remains a subject of debate. Many theories suggest it could be a side effect of syphilis or lead poisoning, scarlet fever, or even rumors that his deafness resulted from his habit of soaking his head in cold water to stay alert.

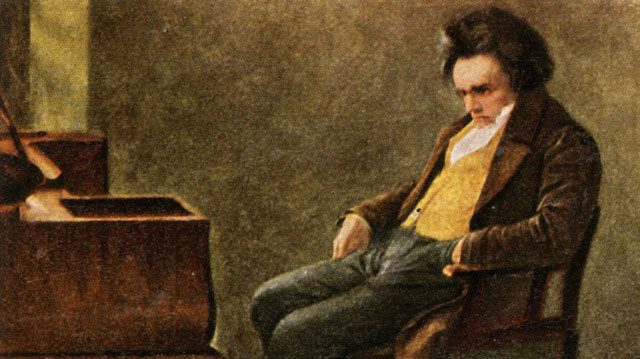

Beethoven himself also suffered, struggled, and did not accept his condition.

Even Beethoven himself never explained the reason for his hearing loss. At one point, he claimed it was a result of a stroke he suffered in 1798, while others suggested it was due to stomach illness.

After the composer’s death, an autopsy was conducted. It was discovered that he had a severely damaged and swollen inner ear.

How Did Beethoven Compose Music When He Could No Longer Hear?

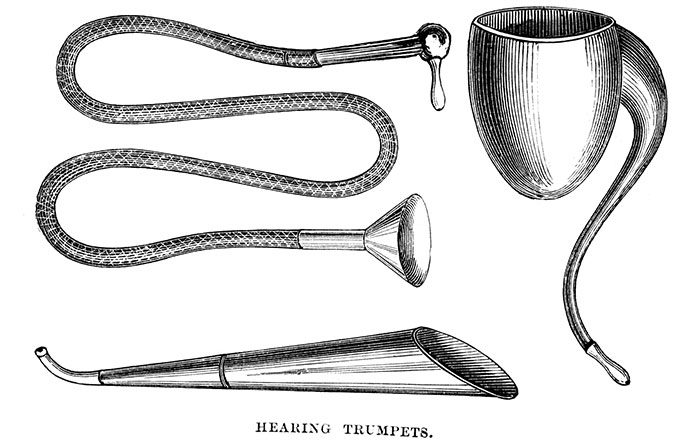

Clearly, for a musician, deafness tormented the German composer for half of his life. It wasn’t until 1822 that he finally abandoned attempts to treat his hearing and accepted the painful truth. Beethoven also used some hearing aids, but at that time, their effectiveness was limited.

Some hearing aid devices and instruments from the 19th century

Despite this, Beethoven continued to compose and even achieved great success; his career was not adversely affected despite his inability to hear. The explanation for this is not difficult to find. Scientists state that Beethoven had heard and played music for the first three decades of his life. More than anyone else, he understood all the rules of instruments and vocals, how music would sound. Additionally, his deafness was a gradual decline in hearing over time, not an abrupt loss. Therefore, the composer could still imagine in his mind what his works would sound like.

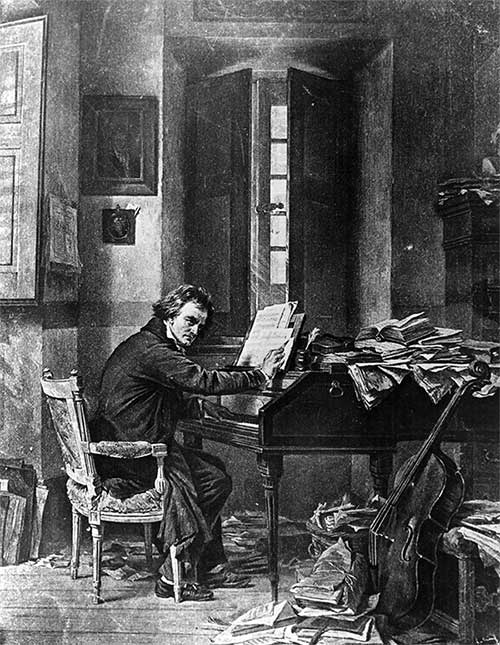

Having a deep understanding of music, Beethoven could compose from imagination

Beethoven’s staff reported that when his hearing significantly declined, he would sit at the piano, place a pencil in his mouth, and touch the other end to the piano’s soundboard to feel the vibrations of each note. Throughout the last 20 years of his life, Beethoven composed music from his memory and imagination, rather than through his ears. Not only did he continue to compose music, but he also performed and conducted orchestras after becoming deaf.

Beethoven’s extraordinary musical talent is undeniable, even when faced with the challenge of deafness. However, despite the quality of his works remaining high, modern experts believe that deafness did have an impact, altering Beethoven’s music.

In his early works, when he could still hear all frequencies, he frequently used high notes. As his hearing declined, Beethoven began to use lower notes more often because those were the notes he could hear clearly. High notes returned in his compositions later in life, indicating that he had “heard” the works taking shape in his imagination masterfully.