Tanks, self-propelled guns, and armored vehicles manufactured by Germany during World War II are characterized by their distinctive appearance, particularly the raised patterns on their surfaces. This design was not a result of lazy craftsmanship but rather a deliberate choice.

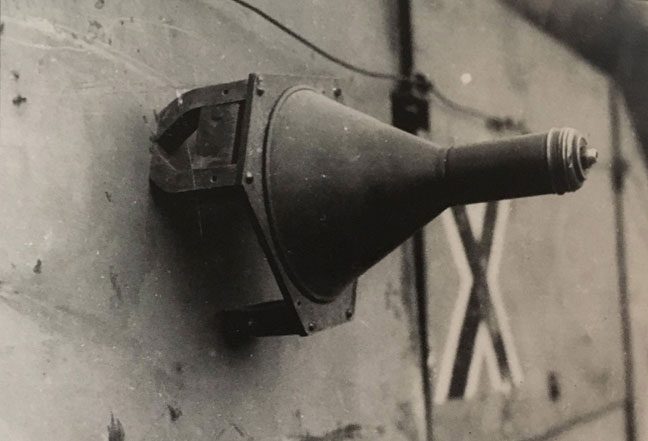

In November 1942, the Nazi German army introduced a type of weapon known as the Hafthohlladung (adhesive hollow charge), also referred to as the Panzerknacker (tank breaker). This is a conical anti-tank mine featuring three magnets at its base, each magnet having a pair of poles that create a very strong magnetic field, allowing it to adhere tightly to the surface of a tank from any angle. This anti-tank weapon was primarily used by Wehrmacht tank destroyer teams. Upon detonation, the Hafthohlladung could penetrate up to 140 mm of homogeneous armor, significantly greater than the thickness of most Allied tank armor.

However, Germany was concerned that the Allies might develop a similar weapon capable of adhering to tanks using magnets. To counter this “sharp nail” threat, the German chemical company Chemische Werke Zimmer & Co devised a solution to make the “orange peel” surface immune to magnets. They developed a magnetic coating, which ultimately became known as Zimmerit.

Zimmerit was introduced in December 1943 and, in essence, did not possess any particularly unique anti-magnetic properties. It was simply a thick paint designed to prevent direct contact between magnets and the metal surface of the vehicle. The composition of Zimmerit included 40% barium sulfate, 25% polyvinyl acetate, 15% pigment powder, 10% zinc sulfide, and 10% sawdust. In addition to its magnetic resistance, Zimmerit was applied to tanks in the form of raised patterns, reducing the adhesive capability of magnets due to the uneven surface and also serving as camouflage.

Zimmerit was applied to vehicles at factories or supplied to operational units for application directly on the battlefield. Two coats were typically applied, with the first coat being painted and allowed to dry for 24 hours before the second coat was added. The second coat was then scraped to create the raised patterns, which, upon drying, formed a rough and hard surface. If painted at the factory, the pattern could resemble square waffle shapes.

The German army utilized Zimmerit on various tank models, anti-tank vehicles, and self-propelled guns, including the Panzer III, Panzer IV, Panther, Tiger, and even early models of the Tiger II. Initially, Zimmerit was required to be applied to the hull of the vehicle, followed by the turret.

However, just one year later, Zimmerit was no longer used on German tanks or armored vehicles. The fear that the Allies might use similar magnetic mines like the Hafthohlladung to attack German tanks did not materialize. Instead, the emergence of high-explosive anti-tank weapons like the Bazooka rendered devices such as magnetic mines obsolete, thereby making the Zimmerit coating ineffective. Additionally, there were unfounded rumors about Zimmerit being flammable when struck, combined with the drawback that the paint required considerable drying time—something the German military was unwilling to waste in the later stages of the war.