You may not know that the Kiwi is the only bird in the world with external nostrils at the end of its beak.

The wingless characteristic and extraordinary sense of smell of New Zealand’s national bird, the Kiwi, are results of adapting to their specific ecological niches, enabling them to survive and reproduce effectively.

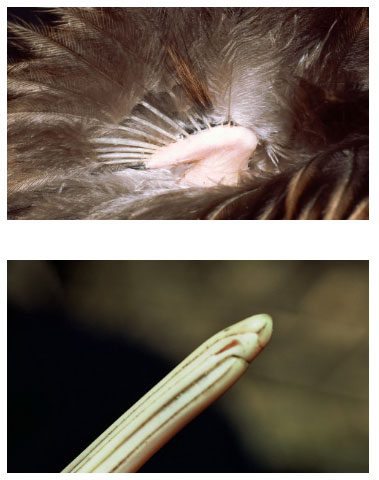

Kiwi is also the only bird in the world with external nostrils at the end of its beak. Its nostrils and keen sense of smell help the Kiwi locate food in the leaf litter, but this adaptation comes with drawbacks. Having nostrils too close to the food source means that dirt can easily enter their ‘nose’ while hunting. The snorting and snuffling sounds that Kiwis make are noises they produce when trying to clear the dust from their nostrils.

Firstly, Kiwis live in relatively isolated environments; New Zealand’s island ecosystem lacks large terrestrial predators. In such an environment, flying is not a necessary survival trait, leading to the gradual loss of flight capability in the ancestors of Kiwis through evolution. This adaptation allows Kiwis to “invest” energy in other beneficial abilities for survival in their habitat, such as enhancing their olfactory and auditory senses while improving reproductive success.

The beak of the Kiwi is not just a very sharp version of a nose. It also serves as a vibration detector. Kiwis have sensory pits at the tip of their beaks, allowing them to feel prey moving underground. For a hungry Kiwi, sensing vibrations from prey may be more critical than smelling. At this time, the sense of smell can mainly be used to explore the surrounding environment. Kiwis can even perform the act of planting their heads down with their beaks.

The superior sense of smell of Kiwis is part of their survival strategy. Since they are primarily nocturnal and have poor eyesight, they rely on their sense of smell to find food and navigate their environment. Kiwis’ diet includes insects, snails, spiders, worms, crustaceans, fruits, and berries on the ground, foods that are often hidden beneath the surface or within vegetation, making their keen sense of smell essential for foraging.

Moreover, the olfactory abilities of Kiwis also help them navigate complex forest environments, find mates, and avoid potential predators. This enhancement of senses is a result of Kiwis adapting to their habitat and is a product of natural selection and evolution.

In summary, the wingless trait and keen sense of smell of Kiwis are the results of their adaptation to a specific ecological environment, enabling them to survive and reproduce successfully in New Zealand.

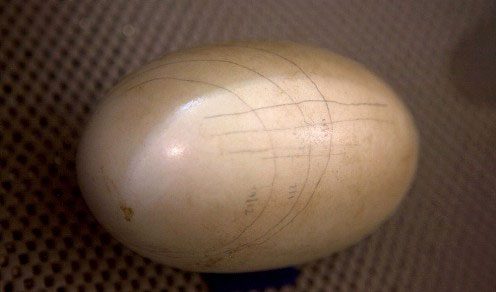

Kiwis also lay large eggs—equal to 20% of the female’s body weight—making their eggs larger compared to those of most other birds of similar size. In fact, Kiwi eggs are six times larger than what would be expected for a bird of that size. While ostriches lay the largest eggs in the world, their eggs are the smallest compared to the mother ostrich’s weight—only 2% of her body weight.

Scientists once believed that the Moa and Kiwi of New Zealand evolved from a common ancestor when New Zealand separated from Gondwana, and later thought that Kiwis were a branch of the lineage of emus—after all, they are both flightless birds. However, DNA tells a different story. The little Kiwi turns out to be a relative of the giant elephant bird.

Most bird eggs have 35-40% yolk, but Kiwi eggs contain 65% yolk. The nutritious yolk produces large newly hatched Kiwis that can sustain themselves, and Kiwi parents rarely need to feed their young.

After studying the DNA of the extinct giant elephant bird from Madagascar (Mullerornis agilis), scientists now believe that it is the closest relative of the Kiwi. Similarly, DNA studies show that Moa is “older” than Kiwi in evolutionary terms—their ancestors diverged from the lineage of running birds long before the common ancestor of Kiwis and ostriches.

DNA also reveals that the closest relatives of Moa are Tinamou, a large group of small, weak-flying birds found in Central and South America. Thus, Kiwis are related to a large flightless bird in Africa, while Moa are related to several small, nearly flightless birds in the Americas.

Kiwis not only do not resemble any other bird species but also, in some ways, resemble nocturnal mammals, using their sense of smell to forage at night. They build burrows like badgers, where they sleep standing. Their body temperature is lower than that of most birds, ranging from 39°C to 42°C, while Kiwis maintain a temperature of 37°C to 38°C.