Marie Curie was a Polish-born French physicist and chemist. She is regarded as a pioneer in the study of radioactivity.

Born in Poland in 1867 and later acquiring French citizenship, Marie Curie (born Maria Salomea Skłodowska) has become a household name today. However, long before she became a revered scientist, Marie Curie was a curious child with an excellent memory and a passionate love for learning—perhaps partly due to the influence of her father, a mathematics and physics teacher (according to Britannica).

However, the path to becoming a scientist was not easy for her. Women at that time were not allowed to attend universities in Russia or Poland, so there were periods when she had to seek knowledge through tutors (according to Atomic Archive). It wasn’t until she moved to Paris that Marie Curie was allowed to attend a university—the prestigious Sorbonne—where she pursued her passion for research in chemistry and physics. Eventually, she became the first female lecturer at this university.

At the age of 26, she worked in a research laboratory, and a year later, she met Pierre Curie, who would not only become her husband but also her research partner. After scientist Henri Becquerel discovered the phenomenon of radioactivity in 1896, the Curies focused their research on this issue and soon discovered the elements polonium and radium (both of which earned Nobel Prizes). Even then, the path to recognition in the scientific community was challenging for the couple. Most of Marie Curie’s laboratory work was conducted while she was writing her doctoral thesis, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

The Curie family.

Building on the work of Becquerel and Wilhelm Röntgen (who discovered X-rays in 1895), Marie Curie dedicated the following years of her life to researching uranium and understanding the spontaneous radiation it emitted. Ultimately, the Curies successfully isolated polonium and radium, with Marie Curie referring to these elements as “radioactive substances”—a term that remains in use today, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine.

Marie Curie spent many years working in a laboratory with poor facilities, lacking proper ventilation and access to the materials and tools necessary to isolate and study the new radioactive elements she had discovered. Smithsonian Magazine points out that her ability to continue her work under these circumstances—despite becoming increasingly ill due to radiation exposure—was a significant achievement.

Finally, when she presented her thesis on radiation at the Sorbonne in 1903, she became the first woman in France to receive a PhD in physics. That same year, her husband and Henri Becquerel were nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics for their research on spontaneous radiation, but Marie Curie’s name was overlooked because she was a woman. It took considerable effort from within the nomination committee for Marie Curie to be added to the list. Consequently, Marie Curie also became the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize (according to the American Institute of Physics).

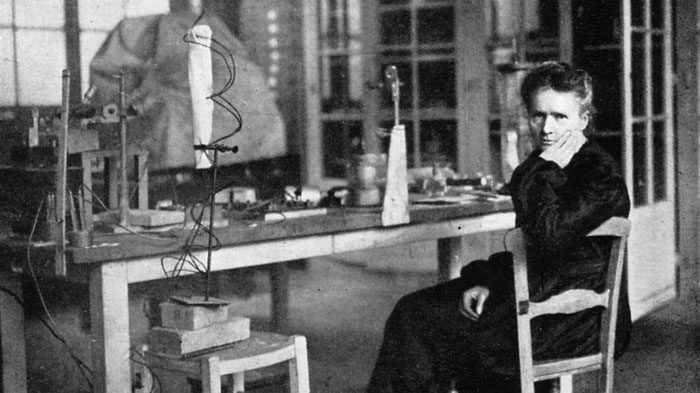

Marie Curie in her office.

This Nobel Prize had a significant impact on Marie Curie’s work. The prize money helped improve the laboratory, and the couple could hire an assistant, although it also made them famous and temporarily reduced their productivity (according to the American Institute of Physics).

Unfortunately, Pierre Curie passed away after being struck by a horse-drawn carriage in 1906, and Marie Curie had to suppress her grief and continue her work while raising their two daughters. Inspired by her work and talent, the Sorbonne invited Marie to take over the class her husband had taught for many years, and a few months after his death, she did just that, becoming the first female professor at Sorbonne.

However, Marie Curie did not give up her research work; she continued to focus on isolating radioactive elements, ultimately isolating pure radium and proving it to be an element on the periodic table.

She succeeded, and in 1911, Marie Curie was awarded her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her work in discovering polonium and radium, according to Smithsonian Magazine. This discovery was not only impressive scientifically but also opened many doors in medicine. When World War I broke out in 1914, Marie Curie, along with her daughter Irène, established the first military X-ray centers, saving countless soldiers by helping doctors locate bullets or broken bones. To this day, Marie Curie remains the only woman in history to have been awarded two Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields.