Recent studies have shown that traces of uranium persist in the shells of turtles decades after World War II.

The impacts of past nuclear activities always leave detectable chemical traces. Isotopic signals from nuclear tests and attacks often leave a mark in the environment both near and far from the explosion sites.

Now, researchers have also found these signals in an unexpected place: the shells of freshwater and marine turtles. This discovery seems to have no adverse effects on the animals but could be useful in tracking radioactive elements in nature.

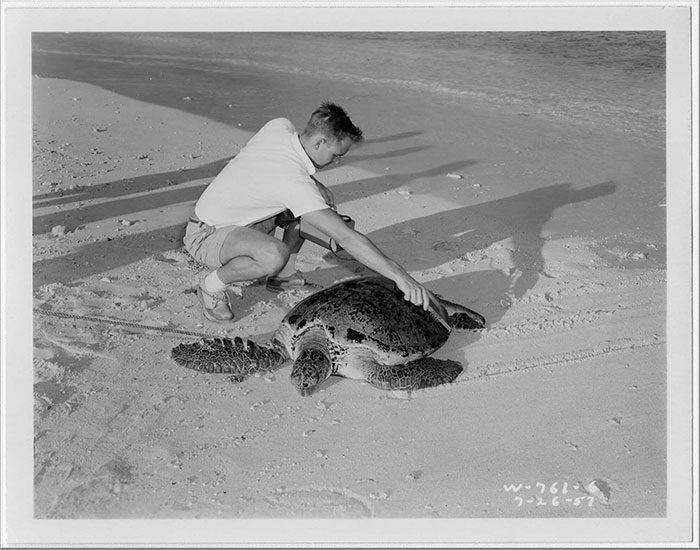

Turtles are long-lived animals capable of accumulating radioactive nuclei generated by humans or from the environment, indicating that turtles can record information about human impacts on the nuclear landscape over extended periods. (Image: ZME).

During the Cold War, the United States developed a large arsenal of nuclear weapons. Although these weapons were never used in warfare, they were tested, resulting in nuclear contamination in the environment.

It is estimated that around 30-80 million cubic meters of soil and 1.8-4.7 million cubic meters of water were contaminated during these nuclear tests. Cyler Conrad from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory wanted to see if this contamination appeared in biological samples. Specifically, Conrad and his team explored turtle shells to search for traces of anthropogenic uranium. They examined the shells from five different specimens at sites related to uranium accumulation.

Remarkably, they discovered that turtle shells can preserve a timeline of exposure to atomic materials.

Radioactive contamination occurs when radioactive substances are present or deposited in the atmosphere or environment, happening randomly and posing an environmental threat due to radioactive decay. The destruction caused by radioactive substances is due to the emission of dangerous radioactive ions such as beta or alpha particles, gamma rays, or neutrons in the environments where they exist. (Image: New Scientist).

Uranium signals were found in a green sea turtle from Enewetak Atoll, located in the Republic of the Marshall Islands deep in the Pacific Ocean. A desert turtle from southwestern Utah near the Nevada National Security Site also showed traces of uranium, as did a river turtle from South Carolina and a box turtle from Tennessee, where nuclear weapon tests were conducted after World War II.

The turtle from Enewetak Atoll was collected in 1978, about 20 years after nuclear testing ended at that site. The most contaminated shell of the box turtle was the layer in which it was born, indicating that the level of contamination on its shell was even higher than that of its mother, which is surprising given that its mother may have been closer to the original nuclear test.

In their study, the researchers used a mass spectrometer – a device that detects the chemical components of materials. The shells were not radioactive, and the health of the animals was unaffected, but traces were clearly detectable.

According to the study, the shells of hatchling turtles are most susceptible to this radioactive contamination, even more so than their mothers. (Image: Zhihu).

The researchers were astonished that they could detect uranium and match the isotopic signals with the nuclear history of the site. Speaking to Scientific American, Conrad expressed hopes that their technique could be used by scientists trying to understand where and when nuclear activities occurred and how nuclear materials moved into animals. Despite the vast legacy of nuclear testing, we still do not know exactly how the natural world has been affected.

Ultimately, the study highlights the persistent existence of nuclear testing footprints on Earth and their connection to the natural world, transcending generations and species. The decay of radioactive elements fuels nuclear weapons. However, the creation and detonation of these weapons will disperse these elements, which will then enter the ecosystem through soil and water.

In the modern world, many forms of energy have been explored. Among them, nuclear energy is considered one of the most potential energy sources. Reports indicate that nuclear energy poses high dangers due to their high levels of radiation. (Image: New Scientist).

Germán Orizaola, a researcher at the University of Oviedo in Spain, who was not involved in the study, told New Scientist that this research could be a breakthrough for ecological radiation studies using zoological collections in museums. Clare Bradshaw from Stockholm University also mentioned to New Scientist that this technique could be applied to living turtles.