Modern humans (Homo sapiens) have overcome numerous challenges throughout evolutionary history, possibly due to their social and behavioral advantages.

300,000 years ago, a relatively short time in evolutionary history, at least nine human species roamed the Earth. However, from about 40,000 years ago to the present, only modern humans, or Homo sapiens, remain. This raises one of the biggest questions in human evolutionary history: What happened to the other human species? There are many theories surrounding the disappearance of modern humans’ relatives, and recent studies are providing intriguing clues, as reported by the Guardian on November 20.

Illustration of Homo sapiens or modern humans. (Photo: Science Picture Co/Alamy).

Around 300,000 years ago, the first populations of H. sapiens appeared in Africa. They did not look exactly like modern humans today, but they resembled us more than other species. They also had chins, a feature that no other human species possesses (though experts are unclear why only H. sapiens developed this protruding trait).

The timing of when modern humans migrated out of Africa is also debated. Genetic evidence suggests a major migration from the continent occurred roughly 80,000 to 60,000 years ago. However, that was not the first journey. Scientists found a H. sapiens skull in Apidima, Greece, dated to at least 210,000 years ago.

A significant advantage of H. sapiens appears to be their population size. From the genomes of Neanderthals and Denisovans, researchers infer that these species lived in small groups and frequently interbred.

“Neanderthals and Denisovans had small population sizes, so interbreeding occurred more often, and genetic evidence reflects this,” said Professor Eleanor Scerri at the Max Planck Institute for Human History (Germany). The lack of genetic diversity made these populations more susceptible to diseases, leading to poorer survival rates.

In contrast, H. sapiens had larger groups and higher genetic diversity. “In H. sapiens, we see larger social networks that span wider areas. A vast network provides a form of ‘insurance’ because if you have connections with people far away, during environmental crises like food or water shortages, you can move to their surroundings. They are not enemies but your relatives,” explained Chris Stringer, a professor at the Natural History Museum in London.

He further noted that social networks also facilitated the exchange of ideas, techniques, and new tools among modern humans. This social resilience may have helped them survive climatic changes that led to the extinction of less adaptable individuals and species.

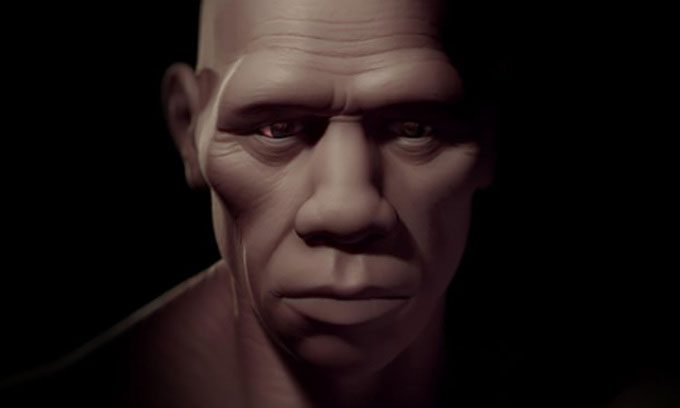

Reconstructed face of a Neanderthal man. (Photo: Cícero Moraes)

Stringer believes that many advantages helped H. sapiens outpace their relatives, such as the ability to weave or sew. “Once you know how to weave, you can make baskets or nets. A needle helps you seal materials better, leading to better insulated tents that can keep infants warm,” he noted. The large social networks also enabled H. sapiens to widely share these techniques.

Another possibility is that H. sapiens assimilated their relatives into their gene pool. Scientists have found genetic evidence for this, though whether this caused the extinction of other species remains debated. For instance, some modern humans living in Eurasia carry about 2% Neanderthal DNA, while some groups in Oceania have about 2% to 4% Denisovan DNA.

It is likely that the survival of modern humans to this day is largely due to behavior and luck. This remains crucial in addressing the challenges ahead. “Social networks are very important, and the ability to adapt to change is also vital. This is certainly something we will all face with climate change. Humanity will confront the need to cooperate in the face of these crises or compete. And what we see from Neanderthals and H. sapiens is that the group that cooperates better will prevail,” Stringer concluded.