A recent study has shown that a small variant in DNA may have helped Homo sapiens compete with our ancient relatives—the Neanderthals.

When Homo sapiens (the ancestors of modern humans) first appeared on Earth around 300,000 years ago, they were not the only human species roaming our planet. Our ancestors were one of about nine early human species that existed at that time and one of at least 21 human species that have ever lived on Earth, although the exact number remains a topic of debate within the scientific community.

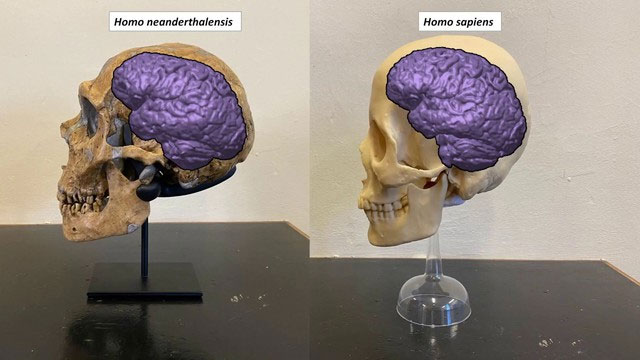

The next question scientists ponder is why only Homo sapiens have survived to this day. After all, our relatives, the Neanderthals, had brains similar to ours but went extinct around 40,000 years ago.

When Homo sapiens arrived in Europe 40,000 years ago, there was already a native group living there—the Neanderthals. It is unclear when the Neanderthal lineage diverged from that of modern humans; studies suggest various timeframes, ranging from around 315,000 years ago to as far back as 800,000 years ago.

“Neanderthals were in Europe long before us, and they certainly adapted to the environment and climate there before our ancestors, including various pathogens. The big question is why we were able to compete with them,” said Laurent Nguyen, a neuroscientist at the University of Liège in Belgium, to Hannah Devlin of The Guardian.

For many years, scientists have suggested and dismissed various answers. Chris Stringer, head of the human origins research department at the Natural History Museum in London, told The Guardian: “Better tools, better weapons, suitable language, art and symbolism, and a better brain were key factors that helped our ancestors win the survival battle.”

Now, a new study published in the journal Science has provided a precise answer: a gene mutation in Homo sapiens allows our ancestors to develop more neurons in the neocortex—a brain area associated with cognitive function.

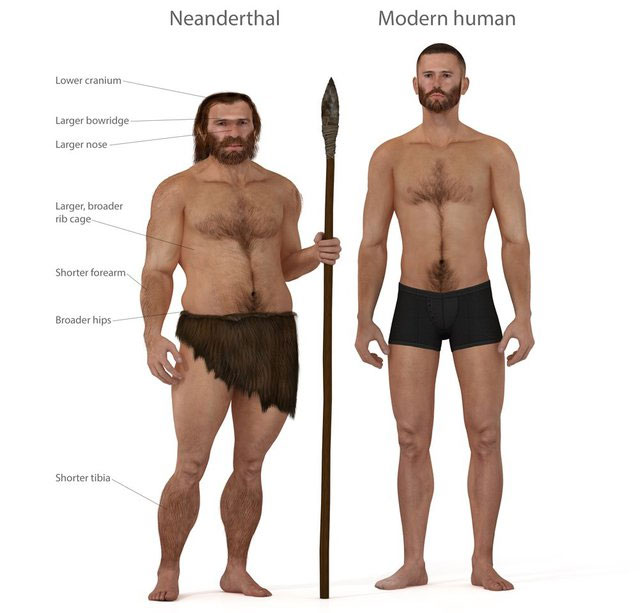

This species stood between 1.6 to 1.7 meters tall, with a large head, broad nose, and heavy brow. A healthy male of this species could overpower our best fighters with just one punch. Essentially, this species is very different from our own.

The modern human gene version—referred to as TKTL1—differs from the Neanderthal version by just one of its amino acid building blocks. This substitution is essentially found in all modern humans, but the extinct ancient humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other primate species lack this mutation.

Co-author Wieland Huttner, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, told Carl Zimmer of The New York Times: “What we found is a gene that certainly contributes to what makes us human.”

In the new study, researchers injected both the Neanderthal version of TKTL1 and the human version into the brains of developing mice and ferrets. The results showed that animals with the Neanderthal gene produced fewer precursor cells that give rise to neurons compared to the others.

Next, the research team removed the TKTL1 gene from human fetal brain tissue. This resulted in the same outcome: fewer precursor cells. In a final experiment, they used brain organoids, or mini brain structures grown in the lab from human stem cells. When they inserted the Neanderthal gene version into these tissues, a similar pattern occurred.

Neanderthals were an ancient human species or subspecies that lived on the Eurasian continent until about 40,000 years ago. While the cause of their extinction remains a “hotly debated” topic, demographic factors such as small population size, inbreeding, and random fluctuations are considered possible causes.

This discovery is “truly a breakthrough,” said Brigitte Malgrange, a developmental neuroscientist at the University of Liège who was not involved in the study, to Rodrigo Pérez Ortega of Science: “A single amino acid change is really significant and can lead to astonishing consequences for the brain.”

Although having a brain with more neurons does not necessarily mean higher intelligence, these findings seem to suggest changes in the neural wiring of the brain, which may have given Homo sapiens a cognitive advantage, according to The Times.

Researchers noted that this single amino acid difference likely does not explain what makes our brains unique. “I don’t think this is the end of the story,” Nguyen told The Times. “I think more work is needed to understand what makes us human in terms of brain development.”