We have many unofficial names for cosmic landscapes. Occasionally, they are named after the shapes we see, such as the Horsehead Nebula. Sometimes they borrow names from their constellations, like the Andromeda Galaxy. But what about our galaxy, the Milky Way? Why does this band of stars stretching across the night sky of Earth have a name related to a beverage?

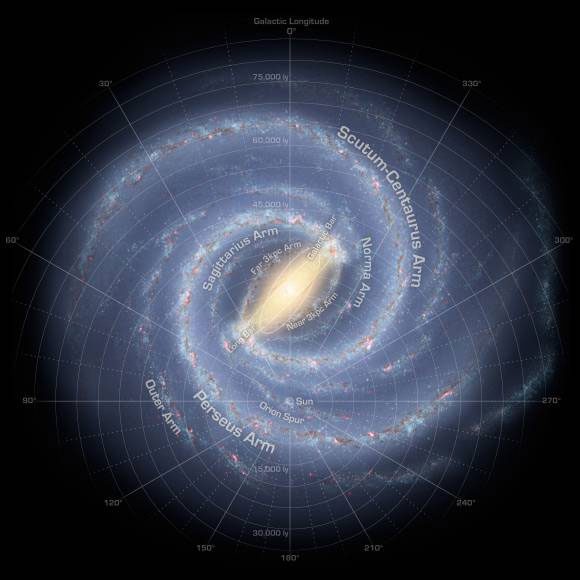

Illustration of the structure of the Milky Way. (Image: NASA)

First, let’s talk a little about the Milky Way. Astronomers believe it is a barred spiral galaxy – a galaxy with a spiral shape that has a straight bar of stars running through its center, as you can see in the image above. If you were to fly through the Milky Way at the speed of light, it would take you about 100,000 years.

The Milky Way is part of a collection of galaxies known as the Local Group. We are on a collision course with the largest and most massive member of that group, the Andromeda Galaxy (also known as M31). The Milky Way is the second-largest galaxy, with the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) being the third-largest. It is known that this group contains about 30 members.

To visualize its immense size, you should be glad to hear that Earth is not located anywhere near the center of the Milky Way and its extremely violent supermassive black hole. NASA states that we are about 165 million trillion miles away from that black hole, which is located in the direction of the Sagittarius constellation.

The magnetic field of the Milky Way created by ESA’s Planck satellite. (Image: ESA)

The name of our galaxy actually comes from its appearance resembling a stream of milk as it stretches across the night sky. While tracing the arms of the galaxy is a challenge when viewed from our light-polluted urban centers, if you venture out into the depths of the countryside, the Milky Way truly begins to dominate the sky. The ancient Romans called our galaxy Via Lactea, literally meaning “The Milky Way.”

According to the Astronomy Picture of the Day website, the Greek root for “galaxy” (galaxy) also originates from “milk.” It is hard to say whether this is merely a coincidence, as the origins of the name Milky Way and the Greek root for galaxy have been lost to history since prehistoric times, although some sources suggest the name derives from the appearance of the Milky Way itself.

It took thousands of years for us to understand the nature of what we are observing. Back in Aristotle’s time, according to the Library of Congress, the Milky Way was believed to be the place “where celestial bodies come into contact with earthly ones.” Without telescopes, it was hard to say much more than that, but things began to change in the early 17th century.

A beautiful view of our galaxy. If there are extraterrestrial civilizations out there, can we find them? (Image: ESO/S. Guisard)

An important early observation, as recorded in texts, was made by the renowned astronomer Galileo Galilei. (He is famous for discovering four of Jupiter’s moons – Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede – which he observed through his telescope.) In his 1610 work Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo stated that his observations showed that the Milky Way was not a uniform band, but had certain regions containing denser star populations.

However, the true nature of the galaxy eluded us for some time longer. Other early observations followed: the stars were part of our Solar System (Thomas Wainwright, 1750 – which was later proven incorrect) and that the stars on one side of the Milky Way were denser than those on the other side (William and John Herschel, late 18th century).

It wasn’t until the 20th century that astronomers realized the Milky Way was just one of many galaxies in the sky. This conclusion came after several developmental steps: observations of distant “spiral nebulae” indicating that their speeds were receding faster than the escape velocity of our galaxy (Vesto Slipher, 1912); observations that a “nova” in the Andromeda Galaxy was dimmer than our galaxy (Herber Curtis, 1917); and most famously, Edwin Hubble’s observations of galaxies showing they were indeed very far from Earth (1920s).

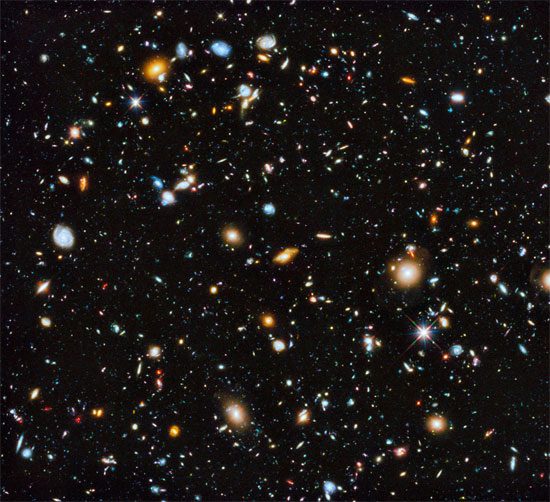

Hubble images in ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light. Image: NASA, ESA, H. Teplitz and M. Rafelski (IPAC/Caltech), A. Koekemoer (STScI), R. Windhorst (University of Arizona), and Z. Levay (STScI)

In fact, the number of galaxies is far greater than we could have imagined a century ago. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have systematically utilized this powerful observatory to survey tiny patches of the sky.

Hubble has provided numerous “deep field” images of galaxies billions of light-years away. It is hard to estimate how many galaxies “are out there,” but estimates suggest there are at least 100 billion galaxies. That number will keep astronomers busy for a long time.