While they may appear similar on the surface, the reasons and purposes for laying crushed stone beneath railway tracks are quite distinct.

For those who enjoy traveling by train, whenever they sit by the window and look outside, they will notice a significant amount of stone surrounding the tracks on which the train runs. However, many do not understand the role that this stone plays in relation to railway tracks.

Many of us may wonder why railway tracks are always covered with a layer of crushed stone. As is known, the design of the tracks consists of two parallel rails that are fixed onto sleepers and all of this is laid on a layer of ballast. How important is this layer of ballast, and why is it necessary?

A layer of ballast laid along the railway tracks.

The term “ballast” originates from the use of stones to stabilize sailing ships, and its function on railways is quite similar. When a train passes, the tracks experience significant stress. It is important to note that 99% of the time, the tracks remain stationary without pressure, but during the remaining 1%, they must support an entire train.

For example, the BHP Iron Ore train in Western Australia is 7,353 kilometers long, consists of 682 open wagons, 8 GE AC6000 locomotives, and weighs nearly 100,000 tons with 82,262 tons of ore, making it the longest and heaviest train in the world according to the Guinness World Records. The sleepers beneath help secure the tracks, maintaining the track gauge while also transmitting pressure from the rails to the ground below. To ensure that pressure is distributed evenly below while keeping the tracks stable under the dynamic load of a moving train, the sleepers are placed on a layer of ballast. Additionally, since the tracks are often exposed to the elements, they must withstand weather factors such as thermal expansion, ground movement, seismic activity, rain, and many other natural factors like weeds and wild plants growing from below.

The longest and heaviest train in the world, BHP Iron Ore.

Two hundred years ago, railway engineers began using various materials to address all of the aforementioned issues. In the past, iron slag and coal dust were used as a foundation for the tracks. However, since the 1840s, ballast has become widely used and is now a crucial component of track structure. Ballast consists of crushed stones with a size of less than 40 mm. These are laid beneath and around the sleepers and possess a property known as “internal friction of the stone aggregate.” This internal friction depends on the arrangement, shape, and size of a collection of small stones. Commonly used hard stones include granite, quartz, and trap rock. If these types of stones are unavailable, sandstone or limestone can be used.

How important is this internal friction? To visualize, think of a mound of sand and a pile of stones of equal height. If you push the sand mound, you will find it moves easily. In contrast, if you push the pile of stones, you will feel resistance. It is not easy to move the pile of stones, and it remains unmoved even with considerable effort. Similarly, when you stand on the sand mound, it easily compresses, while standing on the pile of stones does not cause it to yield. This is precisely the concept of internal friction.

With these characteristics, ballast provides a supportive foundation, enhancing the rigidity, durability, and flexibility of the tracks when trains pass over them. Additionally, ballast helps drain rainwater and snow away from the tracks, preventing water accumulation on the surface, inhibiting the growth of grass and weeds on the tracks, and increasing the elasticity of the tracks against thermal effects.

Ballast possesses high durability and flexibility.

During construction, the thickness of the ballast layer depends on the size and distance between the two rails (track gauge), the traffic volume on the line, and various other factors. However, the ballast layer should not be thinner than 150 mm, and high-speed rail tracks may require a ballast thickness of up to half a meter. If the ballast layer is not thick enough, it can overload the underlying soil, resulting in the worst-case scenario where the tracks may sink. The ballast layer typically sits on a sub-ballast layer (as shown above). This sub-ballast layer serves to prevent water infiltration and supports the track structure above. Without a sub-ballast layer, the rails and sleepers could become inundated, damaged, and lead to train accidents.

A system for cleaning, crushing, and maintaining ballast tracks by Balfour Beatty Inc.

The ballast layer plays a very important role and is regularly maintained. If this layer becomes dirty, its drainage effectiveness decreases, causing debris and dirt to be pulled up from the sub-ballast layer, further contaminating the ballast. Therefore, the ballast layer must always be kept clean, compact, or replaced using various treatment methods such as biological methods, manual labor, or specialized machinery.

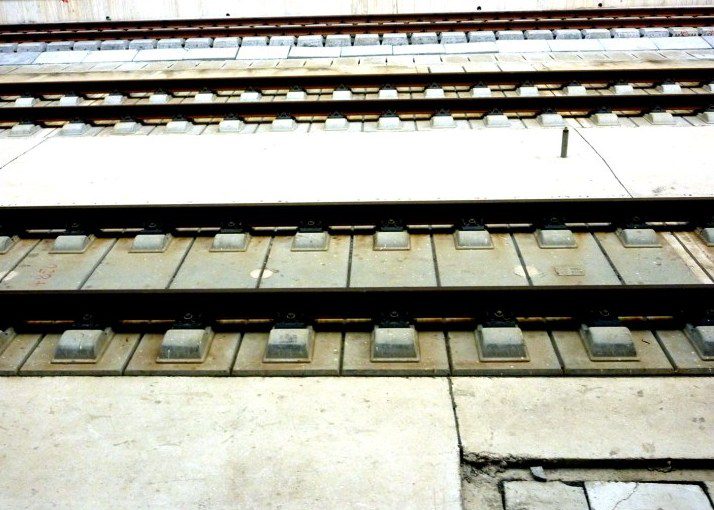

Image of a railway that does not use ballast.

In the face of natural destruction, human activity, and wear from usage, maintaining the ballast layer consumes significant manpower, costs, and time. As a result, the railway industry has also developed and implemented types of railways that do not require ballast (known as ballastless track). Instead of using a supportive ballast layer, continuous concrete slabs are used, with the rails placed directly on top of these slabs. However, due to higher initial costs and the time required for replacement on existing rail lines, ballastless tracks are typically reserved for high-speed or heavy freight rail lines.

Through this article, we have gained some understanding of the role of the ballast layer in railways. In future articles, we will explore more about rail structure, track gauge classification, rail design, and sleeper design.