Far beyond traditional investigative techniques like fingerprinting in the 21st century, the field of forensics has introduced a multitude of fascinating methods for identifying criminals, captivating investigators working in various crime genres. However, many of these methods have not proven to be as effective as anticipated, leading to their decline in current usage.

Throughout the history of criminal investigation, numerous examples exist of investigators striving to uncover new techniques for identifying criminals.

In the 20th century and earlier, various police forces employed psychics to assist in solving crimes. During the Victorian era, scientists, police, and the press seemed to be obsessed with a new scientific process that many believed could forever change the nature of criminal investigations. This was optical investigation—scientists once believed that the last image seen by a deceased person could be extracted from the victim’s eyeball, thereby providing evidence and images of the murderer.

The emergence of optics is understandable when we consider how science evolved in the 1800s and how new discoveries about the nature of life on Earth were integrated into the culture of that time.

As noted by the Museum of Optics, new scientific discoveries and industrial advancements changed how people viewed the natural world. For instance, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, “Frankenstein”, tells the story of a scientist who brings a man to life by assembling parts from deceased bodies. Although this process was never explicitly discussed in the work itself, Shelley later revealed that this resurrection was influenced by Galvani’s theory: the effort to revive dead tissue using electricity, pioneered by Italian scientist Luigi Galvani (according to Public Domain Review). Three years before the invention of the electric motor, Shelley speculated that electrical energy could be the fundamental force behind human life.

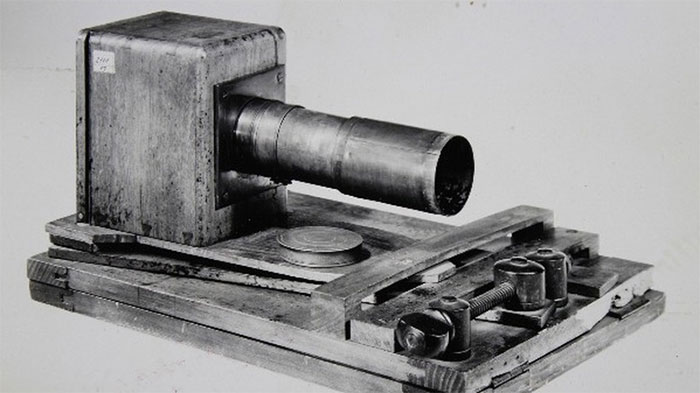

Another remarkable development of the Victorian era was the camera, with the invention of the daguerreotype camera in 1839. Similar to the harnessing of electricity, this new discovery also impacted how Victorians perceived the natural world.

The invention of the camera influenced how Victorians viewed the natural world.

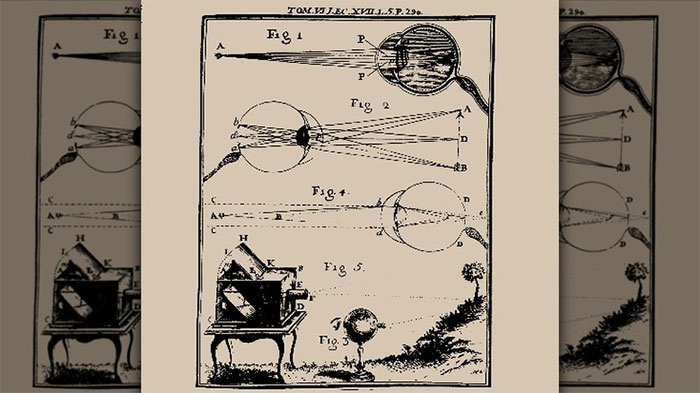

The Museum of Photography notes that after photographic glass plates were introduced in 1851, many urban legends emerged based on this new technique. Similarly, the use of glass plates in photography led people of the time to perceive the camera as a mechanical eye, suggesting that the human eye could function similarly to a camera.

Consequently, intriguing snippets circulated in magazines and newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic, asserting that “the final image formed on the retina of a dying person remains preserved for some time after death.”

Thus, it is no surprise that people wondered whether the retina (or even the entire eyeball) of a murder victim could somehow have recorded an image of the perpetrator.

According to Neuroscientifically Challenged, this speculation is linked to a murder case in Chicago, where investigators reportedly found an image of a man on the victim’s retina, possibly that of his killer. Although this caused quite a stir for a time, the actual content of this claim was never scientifically verified.

Physiologist Franz Christan Boll.

Franz Christan Boll, a German physiologist who died at the age of 30, was the discoverer of rhodopsin, according to the Museum of Photography, a pigment found in rod cells in the eye. This discovery seemed to tacitly confirm that the human eye could also function as a photographic mechanism.

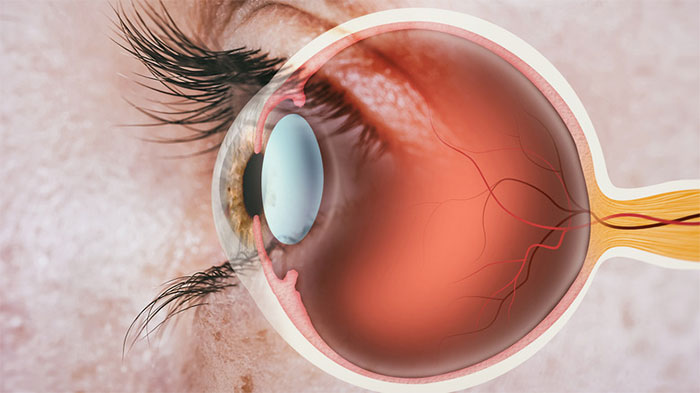

Boll’s experiments on the nature of rhodopsin were later conducted by his colleague. Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne, like Boll, initially experimented on frogs but later switched to rabbits to attempt to extract more detailed visual images from the eyes of deceased specimens. His greatest achievement came from a rabbit’s eye, revealing an astonishingly detailed image of a window that the retina was exposed to at the time of death, according to Neuroscientifically Challenged.

However, Kühne soon identified several challenges in obtaining optograms from the eyes of recently deceased creatures. First, the eyes had to be recovered and processed immediately after death; otherwise, the rhodopsin in the retina would regenerate before visual images could be extracted. Kühne then realized that the eye needed to be held in a fixed position; otherwise, visual images would be obscured multiple times with the same exposure, blurring the image.

Subsequent studies and experiments led Kühne to discover that even at the most opportune moment for extracting images from the retina, the optograms only provided rudimentary images of the light source they were exposed to, suggesting that this method was not viable in science or criminal investigation.

In 1880, he dissected the eye of a man who had been hanged not far from his laboratory in Heidelberg: although bleaching occurred, it was insufficient to provide any identifiable images.

Science may have revealed much of the practical applicability of optics through the pioneering work of Boll and Kühne, but the concept continues to persist in science fiction and detective novels.