The mother duck swims in front while the ducklings swim behind, forming a straight and orderly line. This is not random; it is the coordinated formation that ducks adopt while swimming.

Professor Frank Fish, true to his name, is passionate about fish and the ocean. Moreover, he is enamored with the sight of ducks swimming on the water.

As a biology professor, his research primarily focuses on the dynamics of animal movement. In 1994, Professor Frank published a paper on the swimming behavior of ducks, studying how energy is expended when they swim in groups.

Professor Frank Fish.

However, research on duck swimming behavior did not stop there. In 2021, a research team led by Chinese professor Yuan Zhiming published a new paper on duck swimming. Both studies won the Ig Nobel Prize in Physics.

The Ig Nobel Prize is a parody of the Nobel Prize, awarded annually in early autumn—close to the time when the official Nobel Prizes are announced—for ten achievements that “first make people laugh, and then make them think.” The main purpose of the prize is to create a fun atmosphere that encourages research.

Professor Yuan Zhiming at the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony.

What is it about swimming ducks that captivates so many researchers?

Ducks Swimming as if They are “Surfing on Waves”

Anyone who has observed ducks swimming has likely seen the mother duck leading the way while the ducklings follow in a straight line. This formation is not coincidental; it is a coordinated swimming pattern of ducks.

The reasons why ducks prefer to swim in formation are still under investigation. However, the benefits of this formation are gradually being uncovered. It primarily helps in energy conservation.

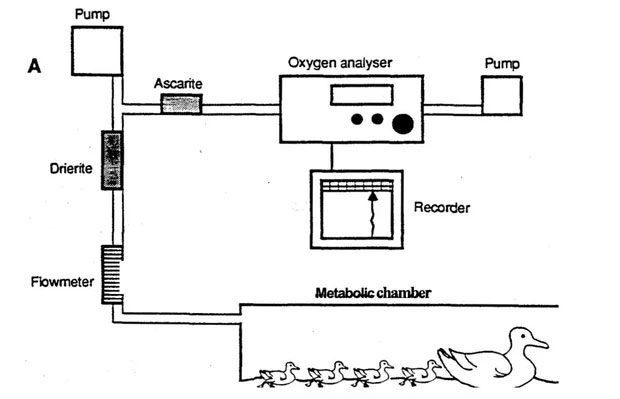

In one experiment, researchers calculated the metabolic rate by measuring the oxygen consumption of the group of ducks.

During the research, Frank trained several one-day-old ducklings to swim in line behind a female duck. Subsequently, the research team conducted experiments on the growth of the ducklings on day three, day seven, and day fourteen.

The results of measuring the metabolic rates of the ducks showed that while the frequency of activity increased, the energy expenditure of each duckling decreased. This experiment validated the hypothesis regarding the metabolic benefits of swimming in formation.

The underlying reason for this “energy conservation” is due to the waves.

The research team led by Professor Yuan Zhiming focused on observing the swimming behavior of ducks over seven years and established a mathematical model, uncovering the secrets of wave oscillation when ducks swim.

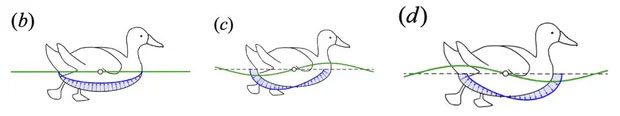

Force diagram of ducks on calm water, with the same wavelength but different phases. (The green line represents the water’s surface, the blue curve indicates the pressure directed at the duck’s body, and the arrows show the direction of the force).

In the “single-file formation,” when the ducklings are in the optimal position behind the mother duck, the wave resistance becomes “positive”—the direction of the resistance aligns with the swimming direction of the ducklings. At this moment, the phase of the waves is shown in figure (d).

In other words, the resistance now becomes a forward thrust, allowing the ducklings to “surf on waves,” enabling them to swim effortlessly. More intricately, this situation can be maintained by the ducklings in formation. The first and second ducklings behind the mother are pushed forward with less energy expenditure. From the third duckling onward, the force acting on each individual gradually approaches zero, achieving a state of dynamic balance.

Thus, it can be seen that the leading ducks help the flock behind them expend less energy. The mechanism of “wave-riding and wave-passing” allows smaller ducks to follow the larger ones without exhaustion or obstruction.

This swimming mechanism helps smaller ducks follow larger ones without exhaustion or obstruction.

Ducks Save Energy, Boats Save Fuel

Not only do ducks swim, but boats also “float” on water. Since ducks are intelligent in their movement patterns, humans cannot lag behind.

A research team from Wuhan University of Technology analyzed different ship configurations and found that the total drag coefficient of boats following a “string formation” is significantly reduced. This means that this movement pattern helps boats conserve energy.

Thinking a bit further, could this principle be applied to all maritime vessels in the future? Professor Yuan Zhiming’s team is exploring related concepts, hoping to bring significant advancements to the maritime transport sector.