For thousands of years, the character “x” has been used to denote an unknown variable in mathematical functions. But where does this character come from, and when did it start being used?

We encounter the letter X in many areas of life. X is defaulted as the letter used to designate an unknown variable in mathematics or to refer to something mysterious, similar to X-files, X-award, X-issues, etc.

So why is it that “X” is the default character instead of any other letter or symbol?

One widely accepted hypothesis among scholars is that the character “x” originated from language differences during the translation of original Arabic mathematical documents. This principle was later popularized by the mathematician Descartes, becoming the standard we know today. What is the truth behind this story? Let’s explore.

The language differences during the translation of original Arabic mathematical documents gave rise to the character “x”

Hypothesis: No Corresponding Sound

Algebra emerged in the Middle East during the golden age of Islamic civilization (from 750 to 1258 AD), with the first mathematical works compiled in the 9th century. During this flourishing period, Islamic laws and civilization spread to the Iberian Peninsula (now territories of Portugal, Spain, etc.). Here, Muslims began teaching various scientific subjects, including Mathematics.

An Arabic mathematical document from Islamic civilization

So how does this relate to the letter “x” in mathematics? According to some researchers, the character “x” came about because Spanish scholars could not translate certain sounds from Arabic. The Arabic term for “unknown” is “al-shalan.” This term was frequently used in early mathematical texts. Since there is no corresponding sound for “sh” in Spanish, the Spaniards replaced it with “sk.” This sound is from ancient Greek and is represented by the letter X (the character “chi.”)

Scientists hypothesize that later, the character X was translated into Latin and became the more commonly used letter x. This is similar to the origin of the term Xmas, where scholars used the letter X (chi) from Greek as an abbreviation for “Christ.”

However, these explanations are merely based on hypotheses and speculations without concrete evidence. Moreover, translators of mathematical works often do not focus on pronunciation but rather on conveying the meaning of the words. Therefore, whether or not there is an “sh” sound is irrelevant to the letter “x.” Nonetheless, many scholars, including mathematicians, still accept this argument.

In the 1909-1916 edition of the Webster Dictionary and other dictionaries, a similar hypothesis is used to explain the origin of the letter “x” in mathematics. Although in Arabic, the word for “thing,” “shei” in singular form, was translated into Latin as “xei” and later shortened to “x.”

Some opinions also suggest that in Greek, the word for unknown is “xenos,” starting with the letter x, so the abbreviation might have originated from there. However, this is also an unsupported argument.

In addition, experts also believe that the letter “X” was designated by the famous mathematician Descartes.

The Random Choice of Mathematician Descartes?

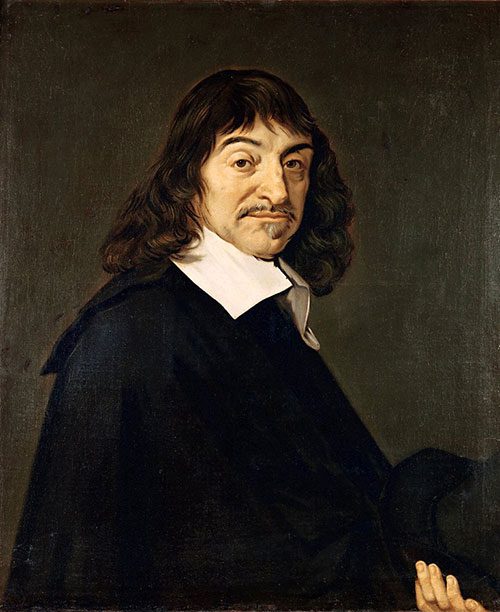

René Descartes (1596-1650), author of the famous mathematical work La Géométrie, used the letter x for unknowns, which has been widely applied ever since

In the subsequent era, the character “x” continued to receive indirect support from the renowned philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596-1650). Although Descartes did not directly dictate this, in his works, most notably La Géométrie (published in 1637), he used letters from the beginning of the alphabet (like a, b, c,…) to denote known values and letters from the end of the alphabet (like x, y, z,…) for unknown values (variables).

A copy of Descartes’ La Géométrie

At this point, you might wonder why y and z are not as popular as the variable “x.” No one knows for sure. One story suggests that it was because the printer of Descartes’ La Géométrie proposed that the character “x” was the least used, and it was also the letter he had the most copies of. This story remains unverified, but in handwritten documents before La Géométrie was published, Descartes had already used “x” as a variable. Moreover, Descartes was not too rigid; he also used all three characters x, y, z to represent both unknowns and known values. This further raises doubts about the accuracy of the hypothesis regarding “no corresponding sound in translation from Arabic.”

Thus, it is possible that Descartes simply chose the letters at his convenience. Either way, one thing is certain: after the publication of La Géométrie, the use of letters a, b, c to denote known quantities and x, y, z for unknowns became a standard practice accepted to this day.

References: Gizmodo, Muslimheritage, Exzuberant, Wiki