Despite the world-famous bust of Nefertiti, there is limited information about this ancient Egyptian queen.

According to DW News (Germany), Nefertiti is considered one of the most powerful women of ancient times—and one of the most beautiful. Although her bust is renowned worldwide, not much is known about this ancient Egyptian queen. Nefertiti seems to gaze into the void, appearing confident and aloof. There is little information available about the woman who lived in Egypt around 3,500 years ago. Her name means “The Beautiful One Has Come.”

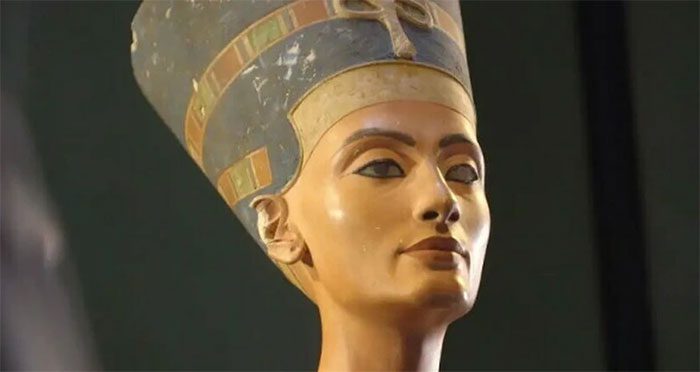

The bust of Nefertiti can be admired in Berlin (Germany). (Photo: DW).

But was Nefertiti tall or short, stern, generous, or haughty? All her personal qualities have faded into history. There are no reports from her contemporaries and no papyrus recounting her life stories. Only a few reliefs and ancient inscriptions provide scant details about the enigmatic Nefertiti.

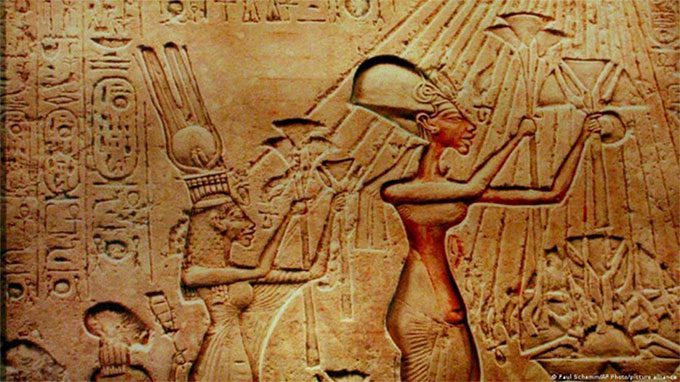

What is known is that at a young age, possibly between 12 and 15, Nefertiti became the wife of Amenhotep IV. He was nicknamed “The Heretic Pharaoh” for abolishing polytheism and subsequently worshipping only Aten—the god of light, depicted as a radiant sun disk.

He also changed his name from Amenhotep to Akhenaten (meaning “Servant of Aten”), while Nefertiti became Neferneferuaten (“Beauty is the Beauty of Aten”).

Olivia Zorn, the deputy director of the Egyptian Museum Berlin at the Neues Museum (Germany), states that Nefertiti held the title “Great Royal Wife” and stood on par with her husband. “They formed a triad, a divine unity, with the god Aten. Aten, Akhenaten, and Nefertiti were almost a governmental unit.”

Ancient relief: Pharaoh Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti worshipping the sun god Aten. (Photo: AP).

A New City for the God Aten

Around 1350 BCE, the royal couple left the capital Thebes (located on the east bank of the Nile River, about 800 km south of the Mediterranean Sea) and briefly established Akhetaten (“Horizon of Aten”), a new royal residence for 50,000 people. The location was the Amarna Plain—a valley protected by steep cliffs (now in Minya Province, Egypt, 312 km south of Cairo).

Akhenaten also built Gem-pa-Aten (“Aten is Found”)—a temple dedicated to his god in record time. However, by proclaiming monotheism, the royal couple created powerful enemies, leaving thousands of priests unemployed.

Akhenaten died during his 17th year of reign. No one knows for sure what happened to Nefertiti afterward. One theory suggests she may have ruled for a time after her husband’s death under the name Smenkhkare. “But it is very likely she died before her husband,” Olivia Zorn states.

“The Most Lifelike Work of Art from Egypt”

Historical records of the subsequent pharaonic dynasty are more detailed, under the legendary Tutankhamun. He and his advisors revived the old gods and destroyed the structures Akhenaten had used to honor Aten, turning them into quarries. The new capital Akhetaten also fell into decline.

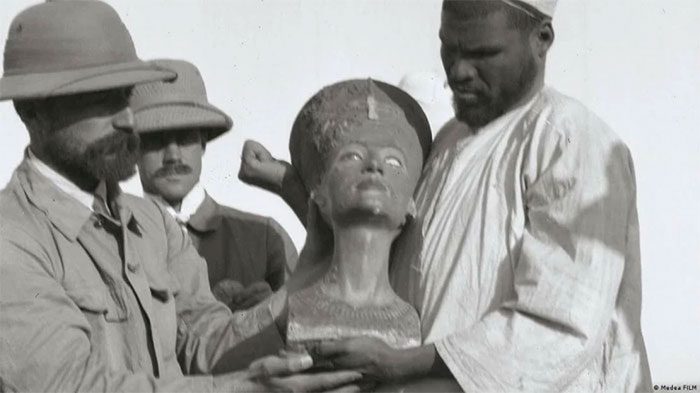

According to DW News, we might never have heard of Nefertiti if the German architect and Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt hadn’t traveled to Egypt in the early 20th century, following the traces of the legendary city of Akhetaten.

Borchardt was commissioned by the last German Emperor Wilhelm II to search for artifacts for the royal museum in Berlin. On December 6, 1912, during excavations, Borchardt and his team accidentally discovered the workshop of a sculptor—who may have served the Egyptian royal family around 1300 BCE.

There were many busts among the ruins, including one adorned with a dark blue crown. The statue’s earlobes were pierced, and its eyes were adorned; aside from the missing left iris, the bust was nearly perfectly preserved.

Borchardt was moved: “We are holding the most lifelike work of art from Egypt.”

German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt brought the bust of Nefertiti to Berlin. (Photo: Medea FILM).

Nefertiti’s crown was a popular headpiece in ancient Egypt, as were the elaborate wigs. The queen’s head was likely shaved—this would make wearing the heavy crowns easier and prevent lice infestations.

“The type of makeup we have today did not exist at that time. But people did adorn their eyes with that lovely eyeliner. It also had antiseptic properties, warding off bacteria that could enter the eyes and cause blindness,” Olivia Zorn, deputy director of the Egyptian Museum Berlin, explains.

Antiquities Exchange

With financial support from the German Oriental Society—an organization that funded Borchardt’s expedition to Egypt—he brought the bust of Nefertiti to Berlin. According to regulations at the time, all artifacts discovered would be evenly divided between Egypt and the nation conducting the excavation (in this case, Germany). Borchardt represented the German Empire.

Gaston Maspero, director of the Egyptian Antiquities Agency under French supervision, authorized his colleague Gustave Lefebvre to arrange the division of the found artifacts. One part included the bust of Nefertiti and others, while the rest was a shrine depicting Pharaoh Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti with their three daughters.

Since the Egyptian Museum in Cairo had never owned a shrine, they decided not to take the bust. Later, Borchardt was accused of storing the bust in less-than-ideal conditions, which led Lefebvre not to recognize its true value.

Nefertiti Meets Modern Beauty Standards

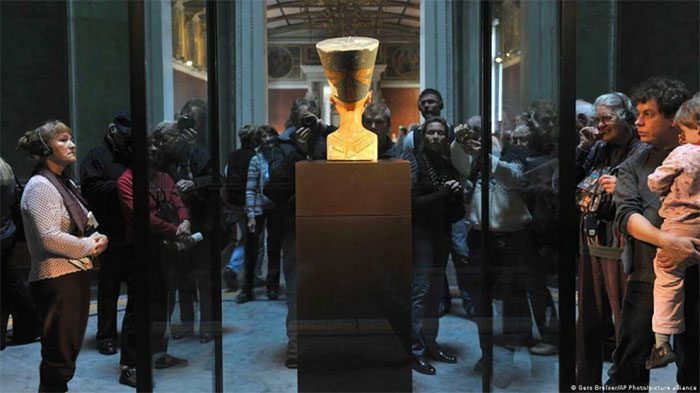

Thus, the “Egyptian Beauty” made her way to Berlin, where she first appeared to the public in 1924, causing a true Nefertiti craze. Images of the bust were featured on magazine covers and used in advertising campaigns for cosmetics, perfumes, and jewelry, as well as beer, coffee, and cigarettes.

Lost in the desert sands for millennia, the bust of Nefertiti became an admired icon.

The film “The Nile Queen” from 1961 with Jeanne Crain as Nefertiti. (Photo: IFTN/United Archives)

“Back in the early 20th century, she [Nefertiti] matched today’s ideal of beauty, with high cheekbones and delicate features,” Zorn notes. However, she adds, “of course, we cannot say for certain whether that was the ideal beauty of 3,500 years ago.”

The Secrets of the Bust of Nefertiti

According to DW News, this colorful bust is not the only image of Nefertiti that has been found. Ancient reliefs depict her hand in hand with Akhenaten in religious ceremonies, or as a devoted mother with her six daughters… and there are other statues as well.

The bust is made from a limestone core, over which the sculptor applied plaster to mimic Nefertiti’s features.

A CT scan conducted in 2006 revealed a wrinkled face carved into the limestone. Zorn explains: “The artist applied a thin layer of plaster over it, similar to how makeup is used with foundation to smooth the skin.”

Nefertiti likely had both eyes, but Zorn has a theory about why the famous bust has only one eye remaining. “It’s simply a model. It was used by the artist as a template for other statues of the queen. That piece of iris was probably used to test with different materials,” she explains.

To recreate Nefertiti’s true face more accurately, her mummy would be needed. “But so far, Nefertiti’s mummy has not been positively identified, despite many attempts,” Zorn notes.

And even if Nefertiti’s mummy is identified one day, there will still be inaccuracies. “Mummies are naturally wrapped. Only bones and skin remain, and the most challenging part to recreate on the face is usually the nose,” Zorn adds.

Today, approximately 3,500 years after Nefertiti’s death, her exact appearance remains uncertain. Yet, thanks to her iconic bust, Nefertiti continues to be a remarkable beauty in the minds of many.

Nefertiti’s bust continues to captivate people around the world. (Photo: AP).

Who Owns the Bust?

According to DW News, Egypt wants to bring back its “famous ambassador”, but Berlin sees no reason to return it.

“There is absolutely no claim for restitution. The legal status is clear. After all, the bust was given to the German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt following an agreement made 100 years ago,” stated Olivia Zorn, Deputy Director of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin.

However, DW News points out that from today’s perspective, the question arises as to whether Egypt had any say in this matter, as the country was under British colonial rule at that time, and the antiquities department was managed by the French.

Zorn quickly rebutted: “The bust is not suitable for relocation for conservation reasons alone. If we were to move it, there would be a risk it would not arrive intact. And I don’t think anyone wants that.”

Therefore, according to DW News, it is likely that the Nefertiti bust will continue to be on trial in Berlin for the foreseeable future.