In reality, the United States once had an extremely developed railway system, but at this point, that no longer seems to be true. Occasionally, we still see railway accidents in this country reported in the media. In 2015, a train from Washington, D.C. to New York derailed, resulting in 5 fatalities and 50 injuries. In 2017, another train derailed in Washington state, causing at least 6 deaths and injuring 77 others. Recently, a derailment on the Empire Builder line connecting Seattle, Washington, and Chicago, Illinois, injured at least 50 people, with many trapped.

Today, as the world’s leading power, why does the United States continue to rely on a railway passenger transport system that does not align with its national strength?

American railways once flourished, driving the U.S. economy.

A Prosperous Development History

American railways once thrived, significantly contributing to the growth of the U.S. economy. In 1825, the world’s first railway was established in England, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. Four years later, the first railway in the United States, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, was completed.

From this point, railway construction in the United States entered a peak phase. Over the next 20 years, the total railway mileage in the U.S. increased to 14,000 km. The emergence of American railways coincided with the rise of economic liberalism in Europe and the United States. As a result, the U.S. railway sector developed a tradition of private investment from the very beginning, similar to other economic sectors at that time.

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, illustrated in 1860, with the red section indicating the railway.

Between 1850 and 1910, the United States built over 370,000 km of railway, averaging more than 6,000 km per year. This is equivalent to constructing three Beijing-Guangzhou railways each year.

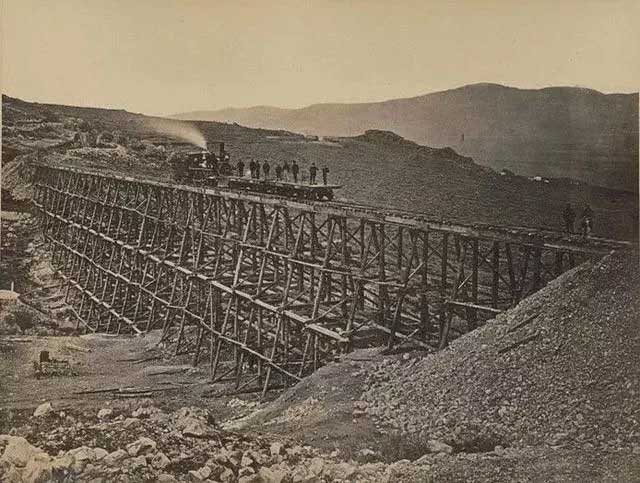

Construction site of the Central Pacific Railroad in 1868.

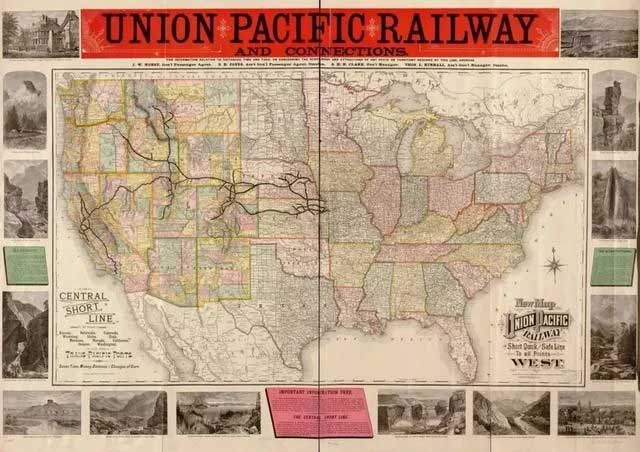

During this period, major rail lines and branches, such as the Santa Fe Railroad, were completed and operational, forming a large-scale railway network crisscrossing the map of the United States.

Map of the Pacific Railroad Union in 1883.

The golden age of American railways coincided with the peak of World War I in Europe. In 1916, total investment in the U.S. railway industry reached $21 billion, nearly double the annual GDP of the United Kingdom before World War I.

In 1916, revenues from U.S. railway companies amounted to $3.35 billion, and the total number of employees in the railway sector was 1.7 million, equivalent to the total number of personnel in the armies and navies of France and Germany before World War I.

At that time, the United States had nearly 600,000 km of railway, accounting for about half of the world’s total railway mileage. In contrast, the total railway mileage of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany was only 150,000 km.

19th-century steam locomotive at the California State Museum.

The government played a crucial role in rapidly elevating the U.S. railway industry to a leading position globally. The federal government did not overly involve itself in railway construction; instead, it focused on creating favorable conditions for development without interfering in the specific operations of railway companies.

To encourage development, the federal government granted a large amount of its land to railway companies for free. Additionally, there were tax reductions and exemptions on raw materials necessary for railway construction, and the federal government provided loans to railway companies based on the mileage of railway constructed.

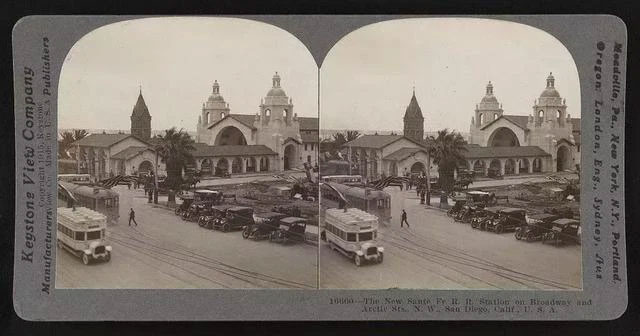

Santa Fe train station in San Diego in the early 20th century.

The railways facilitated smooth transportation for American industry and agriculture, connecting the eastern and western coasts and becoming the golden route for the development of the American West. The enormous capital demand for railway development also directly gave birth to the U.S. capital market, propelling the country towards becoming a financial empire.

The humble yet effective guidance of the government drove the remarkable development of U.S. railways; the railway sector prospered the U.S. economy at that time and helped make the nation great.

Lost in the Competition of Aviation and Highways

Entering the 20th century, the limitations of American railways began to become apparent, such as price discrimination, bureaucratic internal management, and a series of typical symptoms of monopolistic enterprises.

To address these drawbacks, the United States had to implement appropriate intervention measures in railway operations. The railway system remained operated by private companies, but the U.S. adopted legislative measures to freeze fares, reduce investment, limit mergers in the railway sector, and even required railway companies not to abandon “public interest” rail lines and passenger transport even when they were operating at a loss.

The Great Depression dealt an unprecedented blow to the American railway industry. By the time World War II began, over 110,000 km of railway had gone bankrupt. After World War II, the U.S. economy became a driving force for global post-war recovery, yet the American railway industry still had not regained its former glory.

With excessive government intervention, the operation and management of railways became rigid, and in the face of the rapid development of the automobile and aviation industries, railway passenger transport seemed to be losing momentum.

Abandoned railway buildings on the Union Pacific Railroad.

After World War II, U.S. civil aviation led the significant expansion of the global civil aviation industry, with major aircraft manufacturers like Boeing shifting their focus from military to commercial aircraft.

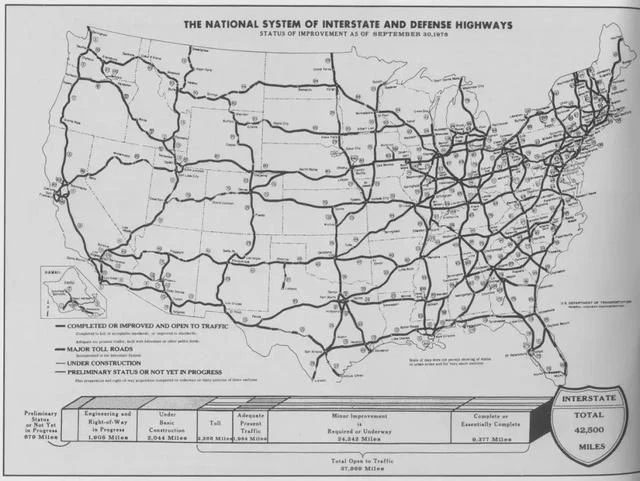

The development of the federal highway system was proposed by Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had commanded on the battlefield during World War II, suggesting the idea of using the federal highway network as a national defense highway system in case of war. During his presidency, he proposed that the U.S. would build 65,600 km of interstate highways over 30 years, with all construction funding covered by federal and state governments.

By 1975, the total number of airports in the United States reached 13,200 (in 2013, the number of airports in China was only 507), and air travel distance reached 600,000 km—doubling the figure from 1946.

Of course, the market share of civil aviation in the 1960s and 1970s was not high, around 5.4%, and the role of replacing railways at that time was still limited. What truly replaced railways during that period were the federal highways; today, there are over 77,000 km of federal highways in the United States.

The highway network built by the U.S. during the early Cold War.

The sudden emergence of road transport put American railways in a deadlock. In 1965, railway passenger traffic in the United States was 85% lower than in 1929.

During this period, not only did American railways fail to increase speed, but they also had to reduce maintenance and safety costs by decreasing speed. The mileage of railways in the United States not only did not increase but also significantly decreased, with many rail lines being dismantled.

In addition to the large-scale construction of federal highways, in 1970, the United States directly intervened in railroad operations through government legislation. In that year, the U.S. enacted the “Rail Passenger Service Act” and established the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, commonly known as Amtrak, which became one of the few federally owned enterprises in the United States.

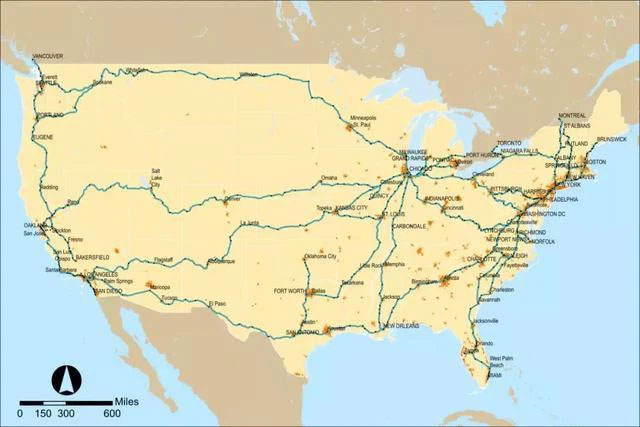

Map of the U.S. railroad system since the establishment of Amtrak.

Challenges and Solutions

Starting in the 1980s, the U.S. government recognized that excessive intervention would not only fail to revive the railroad industry but also put the government in a difficult position. Consequently, the government began to loosen its control over the railroads, allowing railroad companies more freedom in pricing, route selection, and asset restructuring.

As a result, railroad companies continued to increase investments, renovate, and upgrade their lines, particularly reviving freight rail operations. This was no easy task in a country like the United States, which has the most developed road and air transport networks in the world.

In fact, the main issue here is that rail passenger transport is still more expensive than flying and slower than driving. Therefore, restoring the prosperity of the rail passenger transport industry seems nearly impossible.

At this point, high-speed rail appeared to be the answer to this challenging problem. However, the enormous investment required, land acquisition, resettlement, inconsistent planning among states, and protectionist trade policies that high-speed rail construction faces are significant challenges in the U.S. today.

It wasn’t until November of last year (November 2021) that the United States officially had its first high-speed rail line, which is expected to operate on the Northeast Corridor (passing through New York City, Washington D.C., etc.) in the coming months.

Acela is America’s first high-speed train. The Acela can reach a maximum speed of 166.8 miles per hour (equivalent to 268 km/h) and is equipped with features to ensure safety and comfort for passengers, such as an additional 25% seating capacity (a total of 386 seats per train), Wi-Fi, and facilities for disabled passengers…