We all know that boys and girls are typically born at nearly equal ratios. However, how is this 1:1 ratio maintained over thousands of generations? This is a question that scientists have been striving to answer for decades.

Why is the Sex Ratio Balanced?

In earlier times, scientists believed that the 1:1 sex ratio was due to the “arrangement” of a supreme being, aimed at ensuring the survival and continuation of humanity. However, with advancements in science, we now understand that the sex chromosomes are the key factors determining gender formation.

In humans, female gender is determined by two X chromosomes, while male gender is defined by one X and one Y chromosome. The Y chromosome carries a special gene called SRY, which initiates the development of testes, thereby leading to the formation of a boy.

Thanks to the balance between the number of X and Y sperm, the sex ratio at birth is typically close to 1:1.

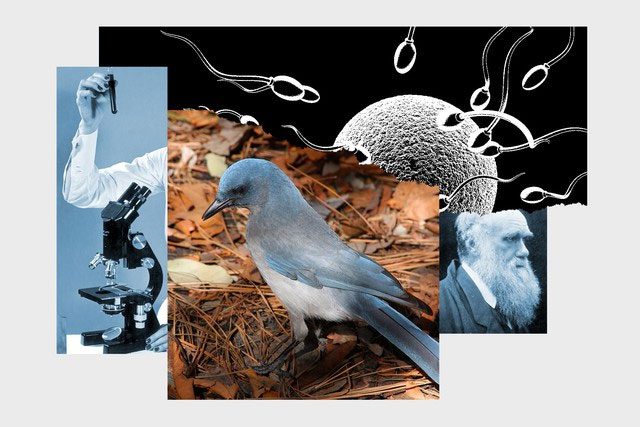

The nearly 1:1 sex ratio is the result of the distribution process of X and Y chromosomes in sperm and eggs. When a cell divides to form sperm and eggs, they only contain a single set of chromosomes. All sperm carry either an X or a Y chromosome, while the mother’s egg always contains an X chromosome. When a sperm fertilizes an egg, if the sperm carries an X chromosome, the result will be a girl (XX); if it carries a Y chromosome, it will be a boy (XY). Thanks to the balance between the number of X and Y sperm, the sex ratio at birth is typically close to 1:1.

Variations in Sex Ratio in Nature

While the 1:1 ratio is quite common, many animal species exhibit significant discrepancies in sex ratios. This is often due to genetic mutations that disrupt the process of chromosomal separation or other biological factors such as the elimination of embryos of a particular sex.

In some species, an unbalanced sex ratio is normal. For example, the small marsupial Antechinus stuartii produces only about 32% males. The kookaburra bird has an interesting trait: the second chick in a nest is usually female because they have a higher survival rate than males in a harsh competitive environment.

Some species even have atypical sex chromosome systems. For instance, polar mammals and some rodent species possess unique gene variations that allow females with XY chromosomes to reproduce normally. In fact, in certain species of cicadas, the sex ratio can reach 15 females for every male, while many fruit fly species have up to 95% of sperm carrying the X chromosome, resulting in a majority of their offspring being female.

In some species, an unbalanced sex ratio is normal.

Fisher’s Principle and the 1:1 Sex Ratio in Humans

So why is the 1:1 sex ratio prevalent in humans? The renowned statistician Ronald Fisher proposed that this ratio is self-regulating and tends to revert to a 1:1 balance unless strongly influenced by evolutionary factors.

Fisher’s argument is quite simple: if there is a deficit in one sex, parents producing offspring of the rarer sex will have more grandchildren because their children have a reproductive advantage. Therefore, genes that increase the likelihood of producing offspring of the rarer sex will be favored in the population, leading to a self-balancing sex ratio. For example, if males become rarer, families with more sons will have an advantage, resulting in an increase in the male ratio until it returns to equilibrium.

But is there any evidence that strong evolutionary forces are at work to maintain the sex ratio in humans? According to a recent study by Siliang Song and Jianzhi Zhang from the University of Michigan, the answer appears to be no. The two researchers analyzed vast genetic data from the United Kingdom and discovered two genetic variants affecting the sex ratio, but these variants were not significantly passed down through generations.

The sex chromosomes are the key factors determining gender formation.

Understanding the Adherence to the 1:1 Rule

So why does the sex ratio in humans still adhere to the 1:1 rule? One possibility is that families tend to have relatively few children, so any significant differences in sex ratio within a single family will be mitigated when looking at the overall population. Additionally, humans may face unique evolutionary constraints, such as monogamous marriage systems, creating pressure to maintain gender balance according to Fisher’s principles, which may not necessarily apply to other animal species.

The study by Song and Zhang raises many intriguing questions about the equality of the sex ratio in humans. Although the genes influencing the sex ratio have not shown clear evidence of transmission across generations, the question of why the 1:1 ratio is sustained remains an interesting mystery, warranting further in-depth research in the future.