Imagine you are walking barefoot in your home and accidentally stub your little toe against the dining table leg. What is the first word that comes to your mind?

For an English speaker, it would be “Ouch!”, pronounced similarly to “ao” or “ái chùi” in Vietnamese. For a Mandarin speaker, it would be “哎哟” (āi yō), which sounds quite similar to our “Ái dồi ôi” .

In a recent study published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, scientists examined how people express pain in 131 different languages around the world. They found that the majority of these exclamations tend to sound quite alike.

Most pain exclamations are often quite similar.

The differences usually arise from the way sounds are transcribed or the writing systems used by different languages to describe these exclamations. But this raises a question: In contrast to the vast linguistic diversity on the planet, why do the pain cries of 8 billion people sound so similar?

Neglected Exclamations

“We all know the words we might shout when we stub our toes or touch something hot. But what kinds of words denoting pain (or exclamations) do speakers of different languages use to express pain?” asked Maïa Ponsonnet, a linguistics researcher at the University of Western Australia.

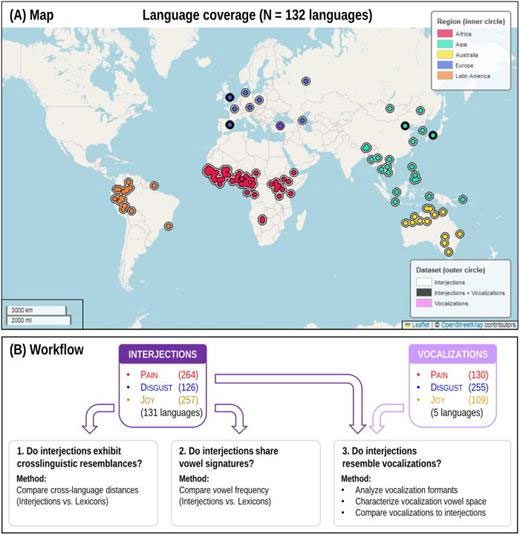

Together with Christophe DM Coupe, an associate professor of linguistics from the University of Hong Kong, and Kasia Pisanski, a linguistic researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), the trio measured the frequency of vowels (a, e, i, o, u) and diphthongs (ai, ao, au…) found in exclamatory words denoting pain across 131 languages globally.

They compared these results with the frequency of similar vowels found in words expressing other emotions such as joy, disgust, and other sound-related words like moans and screams.

“The goal was to determine whether these exclamations sound similar across languages, which we expected if they are a universal reflex,” Ponsonnet stated.

Exclamations are typically used individually, such as “Ái”, “Ối”, “Ouch”, “Wow”…

Exclamations are defined as standalone words used individually, like “Ái”, “Ối”, “Ouch”, “Wow”… They do not grammatically combine with any other words in a sentence to convey meaning. Although sometimes, this phenomenon can be informally created by youth, with phrases like: “You look oh my gosh!“

Because linguists primarily study grammatical combinations and meaningful constructions, they have long neglected exclamatory sentences and exclamations. This is why some fundamental questions about them remain unanswered – even though exclamations occur quite frequently in communication, especially in spoken language, and are a foundational aspect of language.

In the new study, researchers attempted to discover whether exclamations share similar vowels across languages based on the emotions or feelings they aim to express. If so, can these commonalities be explained by the sound forms of non-verbal sounds like crying and moaning?

How the Research Was Conducted

“To test our hypothesis, we collected exclamatory words denoting pain, disgust, and joy from dictionaries spanning various languages in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe. Over 500 exclamatory words in 131 languages were identified,” Ponsonnet explained.

The next step was to compare the exclamatory words with non-exclamatory words. She and her colleagues utilized large databases containing comprehensive lists of words for the sampled languages. This allowed them to run statistical tests to compare the distribution of vowels in exclamatory words with those found in other normal words.

These tests showed that on average, exclamatory words expressing pain contain more “a” vowels and more diphthongs, such as “ai” (as in “ay!” in Spanish) or “au” (as in “ouch!” in English). This was consistent across all languages in all regions of the world.

Exclamatory words denoting pain have more “a” vowels and diphthongs.

“To be clear, this result does not mean that all exclamatory words denoting pain contain the sounds “a”, “ai”, or “au”. But if you randomly choose an exclamatory word denoting pain, it is more likely to have these sounds compared to randomly choosing an exclamatory word describing disgust or joy, or any other word,” Ponsonnet clarified.

Among the three types of emotions the research team examined, pain was the only one with such characteristics. In contrast, the vowels in exclamatory words describing disgust and joy did not significantly differ from those in normal words.

This indicates that the vowels in exclamations denoting pain do not occur randomly. So, where do they come from?

Pain Exclamations as a “Molded” Reflex in Language

“To explore this question, we examined the non-verbal sounds people make to express pain, as well as disgust and joy,” Ponsonnet mentioned.

“We recorded a significant amount of conversations from speakers of English, Japanese, Mandarin, Spanish, and Turkish, using everyday speech – without formal wording – to express these emotional experiences. Then, we counted the vowels in those recordings.”

The results showed that each emotional experience has its own vowel configuration for articulation: the word “pain” has more “a” vowels, the word “bored” has more “neutral” vowels (like the second vowel in “dragon”), and the word “joy” has more “i” vowels.

In other words, both exclamations and non-verbal utterances for pain contain more “a” vowels than expected. However, exclamations denoting boredom and joy do not share the same vowels with the utterances expressing those emotions.

So what conclusion does this lead us to?

Exclamatory words denoting pain may originate from the non-verbal sounds people emit when in pain.

“Our research indicates that while exclamations are common and language-specific, their vowels are not entirely random. Exclamations denoting pain have significantly more “a”, “ai” or “au” sounds than expected. And for “a”, they resemble sounds rather than words,” Ponsonnet said.

“This suggests that exclamatory words denoting pain may stem from the non-verbal sounds emitted by people in pain, although this does not seem to hold true for other emotions.

The findings shed light on significant questions about the origins of language forms. We often think of words as arbitrary combinations of sounds. However, some words seem to share more commonalities than others.

In this context, pain, as a central aspect of human experience, is associated with strong physiological and emotional responses, to the extent that these spontaneous reactions may shape the words people use to describe that pain across all languages, in all dialects and writings.

Ponsonnet noted that the research team still faces many mysteries to unravel: “In this study, we focused on vowels. But this raises the question: what about consonants (“p”, “t”, “s”, etc.)? And what about other emotions beyond pain, disgust, and joy?

Such investigations will further illuminate how human language is expressed and how it evolved in our ancestors, in the early days, at the dawn of speech and writing.”