According to scholar Hoàng Xuân Hãn, starting from the year 1080, the Vietnamese calendar has diverged significantly from the Chinese calendar due to differences in how the two countries calculate time and round dates.

Vietnam and China in different time zones.

During the Lê Trung Hưng period (1533-1789), Vietnam celebrated the Lunar New Year alongside China on 11 occasions.

By 1967, Vietnam officially adopted the time zone GMT +7, while China followed GMT +8. Furthermore, the beginning of the lunar month is calculated internationally starting from 4 PM onward.

In lunar calendar calculations, Vietnam adds 7 hours, while China adds 8 hours.

Every 23 years, the cumulative hour difference adds up to one day. Therefore, some months in the Vietnamese lunar calendar differ by one day from China’s, creating a cycle where every 23 years, there will be a Lunar New Year celebration that differs between the two countries.

As a result, in 2030 and 2053, Vietnam will celebrate the Lunar New Year earlier than China.

How are Vietnamese and Chinese Lunar New Year Similar and Different?

Although Vietnam’s traditional New Year is not imported from China, during the 1,000 years of Northern domination, our culture was influenced to some extent by this great neighboring country.

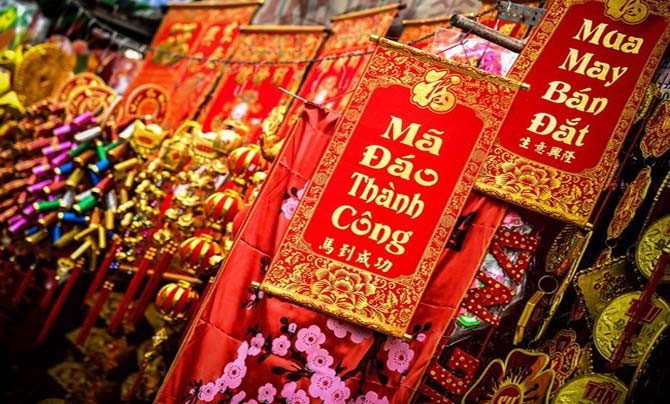

For both the Vietnamese and Chinese people, the Lunar New Year is the most important holiday of the year for families to reunite, gather, and rest after a year of hard work. The predominant color during the New Year celebrations in both countries is red, symbolizing luck and prosperity.

Children are given “lì xì” (lucky money) along with well wishes during the New Year. Especially significant are the meals on New Year’s Eve and the first morning of the New Year, which are sacred moments for both nations.

However, the New Year celebrations in Vietnam and China have many differences due to each country’s unique cultural characteristics. In terms of nomenclature, Vietnam’s Lunar New Year is called Tết Nguyên Đán, whereas the Chinese New Year falls on the first day of the first month of the solar calendar, and their lunar New Year is referred to as Xuân Tiết.

Even though both follow the lunar calendar, the holiday duration differs between the two nations. Vietnam starts the festivities from the 23rd of the last month (Tiễn Ông Công Ông Táo) until the 7th of the first lunar month, while China celebrates from the 8th of the last month to the 15th of the first lunar month.

The Vietnamese Tết is simpler and more genuine, derived from the joy of a bountiful rice harvest after a year of hard work and the anticipation of a new planting season. It is a time for rest and family reunions, where relatives wish each other a prosperous new year.

The Chinese New Year, on the other hand, originates from the legend of fighting against the Nian beast. The Nian beast would come at the beginning of the new year to wreak havoc on livestock, crops, and the people. Therefore, people would place food outside their homes during the New Year so that when the Nian came, it would eat and not attack humans. One time, the Nian was frightened by a child dressed in red, and they realized that the Nian was afraid of the color red. Since then, during the New Year, families hang red lanterns, paste red paper, set off red firecrackers, and wear red clothing to ward off the Nian beast.

Regarding New Year customs, the Chinese have the tradition of hanging the character “Phúc” upside down, as in Chinese it sounds like “Phúc đảo”, which is a homophone for “Phúc đáo”, meaning “Fortune arrives.” They also set off firecrackers and organize lively lion and dragon dances.

In Vietnam, customs are rich and diverse, such as the ceremony to send off the Kitchen Gods on the 23rd of the last month; followed by the bustling days of wrapping bánh chưng and bánh tét, returning home to visit ancestors’ graves, preparing fruit trays, planting Nêu trees to ward off evil spirits, preparing offerings for New Year’s Eve, and on the first day of the New Year, visiting each house to wish for luck, and on the third day, burning offerings…

Traditional food for Vietnamese New Year is bánh chưng (left) while for Chinese New Year it’s sủi cảo (right).

The culinary cultures of Vietnam and China are both exquisite and sophisticated, making the New Year menu very diverse. Vietnam features dishes that are emblematic of Tết such as: xôi gấc, bánh chưng, bánh tét, mứt Tết, nem rán, giò lụa, giò thủ, thịt đông (North), thịt kho hột vịt (South), bò kho mật mía (Central), canh măng, canh khổ qua…

In China, there are various types of Tết sweets, Niên cao cakes, radish cakes, taro cakes, sủi cảo, há cảo, Kung Pao chicken, Peking duck, long noodles, and tea eggs…

Returning to the significance of the traditional Tết for Vietnamese people, it remains a custom, a beautiful tradition passed down through generations, enabling “children of the dragon and fairy” to continue the culturally rich Vietnamese traditions, imbued with the meaning of “drinking water to remember its source.” Along with other festivals, Tết in Vietnam expresses the deep feelings of the ethnic community, connecting generations, bridging the past and present, full of human values and Vietnamese culture.

Regarding the tradition of flower and ornamental tree display during Tết: While Vietnamese people love the trio of “Peach – Apricot – Kumquat” because they believe it brings prosperity and luck to the family, Chinese people favor the combination of “Peach Blossom – Narcissus – Kumquat – Eggplant” for luck, wealth, and health.

Traditionally, Chinese children receive red envelopes as lucky money, which they save and keep under their pillows for about a week before opening them. Vietnamese people can use their lucky money at any time.

New Year cuisine: Vietnam is highlighted by dishes that symbolize Tết such as: bánh chưng, bánh tét, giò, onions, and various other diverse dishes from each region like: pickled onions and dried shrimp, pork braised with eggs, spring rolls, bitter melon soup, etc., in the South; and frozen meat, fried spring rolls, dried bamboo shoot soup, etc., in the North. As for our neighbor from the North, known for its vast culinary heritage, the New Year menu for the Chinese is equally impressive, including: Niên cao cakes, taro cakes, radish cakes, sủi cảo, há cảo, Kung Pao chicken, Peking duck, tea eggs, sweet and sour pork, etc. Some dishes carry symbolic meanings such as fish (the word “fish” is a homophone for abundance), dumplings, Du Giác cakes (New Year dumplings), Chinese noodles (symbolizing longevity) that will be present at the table during the New Year.