Before you read this article, try closing your eyes and pay close attention: What is the first thing you “see”? Surely, it’s not just a pitch-black darkness, right?

Most people, when they close their eyes, see patches of color and flickering lights – a phenomenon known as phosphene. This occurs because our visual system does not completely shut off immediately after the light disappears.

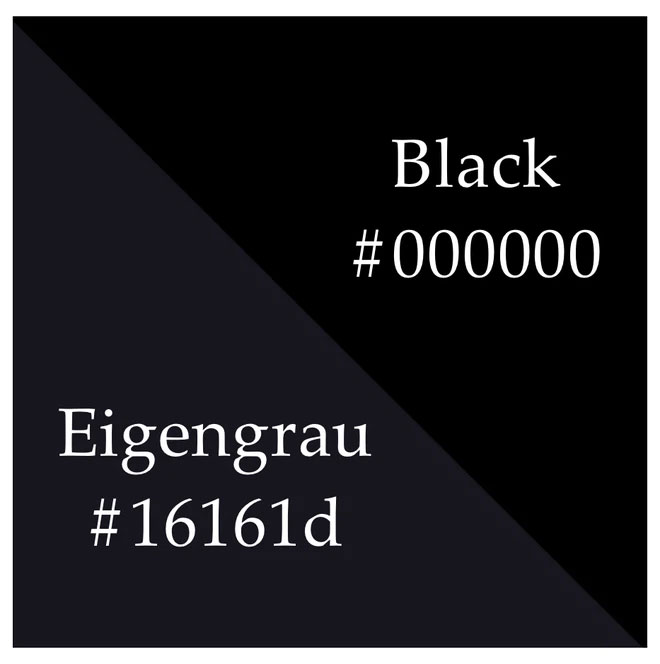

In fact, the darkness you perceive when your eyes are closed is not pure black. Scientists refer to it as “eigengrau” – which in German means “intrinsic gray.”

Intrinsic gray.

Intrinsic gray is what your visual system, including your eyes and brain, perceives in low light conditions. It is not a completely pitch-black color; to experience pure black, you need strong contrasting light.

For example, black ink on white paper appears much darker than the intrinsic gray you perceive when your eyes are closed. This is because the white paper provides the contrast that helps your eyes “understand” the depth of the black color.

When you close your eyes, there is no light and no contrast, and the black you see is essentially eigengrau or intrinsic gray. However, eigengrau is not a static color. The shades of this gray can change while your eyes are closed. As mentioned, there will also be the appearance of phosphene here.

Phosphene is a compound word derived from the Greek roots “phos” meaning light and “phainein” meaning to show. It refers to the phenomenon of seeing light when no actual light is entering the eyes.

When you close your eyes or are in a completely dark room, your eyes can still pick up light signals and create patterns that seem to illuminate against the intrinsic gray background. After a while, these bright patches may diffuse and disappear. But you can also reactivate them by rubbing your eyes with your hand.

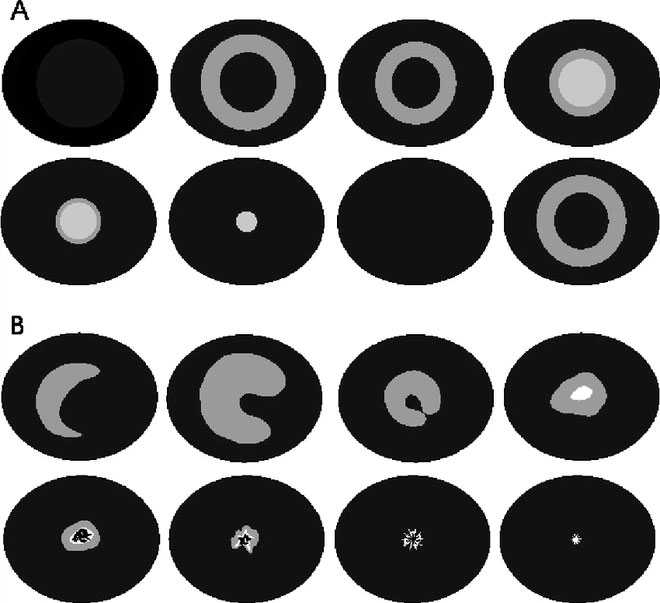

When you close your eyes, you may see one of these 15 common phosphene patterns.

The appearance of phosphene is due to the pressure of your eyelids closing affecting the eyeball and the light-sensitive cells beneath your retina. This stimulates them to send signals to the brain, which interprets these random signals as phosphene.

Since the brain cannot distinguish whether stimuli from the retinal cells are due to pressure or actual light, it will not realize that phosphene is merely an illusion.

In addition to the pressure from closing your eyes, phosphene can also occur in many situations, such as when you rub your eyes, hit your head, or experience external force to your face. A sneeze or blowing your nose can also cause you to “see stars.”

The phenomenon of low blood pressure when you stand up too quickly after sitting can also create phosphene. And although it is less common, phosphene can sometimes be a result of retinal diseases and nerve disorders, such as multiple sclerosis.

Phosphene can also have color, due to the actual bioluminescent light emitted by your eyes.

However, not every phosphene occurs as an illusion. Scientists believe that in some cases, the tissues in your eyes can also emit bioluminescent light that creates photons striking the retina to form images.

Bioluminescent light or biophotonic is light emitted from a living organism’s body, such as fireflies or deep-sea fish. Now, researchers suspect that certain parts of the human eye may sometimes also produce biophotons.

They have been able to replicate this process through stimulation experiments using magnetic fields and electric currents to create colored phosphene without applying pressure to the eyes.

“Different atoms and molecules emit photons with different wavelengths, which is why we see phosphene in various colors,” science journalist Hanneke Weitering explains in Science Line.

Furthermore, the common shapes of phosphene originate from the arrangement of light-sensitive cells on our retina, Weitering adds.

Long before scientists considered the possibility of bioluminescence in the human eye, a study in the 1950s identified and established a chart of 15 phosphene patterns as common variants, as you have seen above.

Not every phosphene occurs as an illusion.

In summary, both intrinsic gray and phosphene are phenomena that occur when our visual system operates like a camera with its lens covered while still recording. That camera continues to operate, capturing and storing every minute and hour of data. The only difference is that this data is not particularly interesting.

Similarly, our retina continues to function fully even when we close our eyes. It continuously records stimuli and transmits impulses through the optic nerve to the brain, translating them into visual images.

Phosphene can then occur in two mechanisms:

One is when the camera is vibrating and its sensors send noisy data back to the processor.

Two is when someone has smeared reflective paint on the lens, and in this case, phosphene is real light and not just an illusion.