With their massive size, the carcass of a whale washing ashore always attracts attention. But do you know what happens when a whale dies and sinks to the ocean floor?

Whales are known to be one of the largest marine creatures and hold a high position in the food chain. With their enormous weight of hundreds of tons, the death of a whale raises many questions. The sight of a whale dying in the wild is a rare event, thus scientists have very few opportunities to study dead whales that naturally sink in the ocean.

Dr. Adrian Glover, a marine biologist at the Natural History Museum in the UK, has shed light on the afterlife of whales. Even in death, they provide life to hundreds of marine animals for up to 50 years. Thus, whales play an incredibly vital role in the life cycle of the Earth’s oceans.

It is estimated that annually, during each migration, about 70,000 whales die. However, their flesh, fat, and bones become a source of life for many other species. One could say that the carcass of each whale is a mini-ecosystem in the deep sea.

What happens to a whale carcass.

Marine scientists have been studying this issue since 1987. To date, they have gained a fairly comprehensive understanding of what happens to a whale carcass.

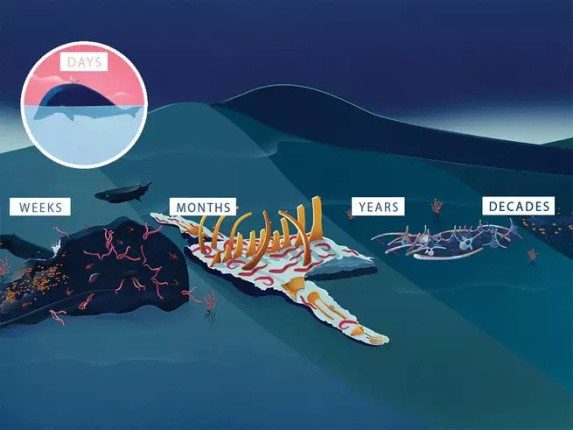

A Few Days Later: The Carcass Swells and Sinks

In the initial stage of decomposition, a whale carcass typically swells and floats.

In the early stage, the whale carcass swells and floats.

However, carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases within the carcass will eventually dissipate. This change causes the whale to sink deep into the water, often hundreds or even thousands of meters.

A Few Weeks Later: A Feast for Sharks, Crabs, and More

The first “guests” to arrive to feed on the whale carcass are crustaceans such as squat lobsters, certain species of sharp-toothed sharks, and this peculiar hagfish.

Squat lobsters and hagfish.

Hagfish resemble eels but are actually a type of fish, measuring between 30 – 90 cm. They have a skull but lack a backbone, specializing in consuming decaying carcasses.

They can feed for several months, with a “menu” that includes organs, skin, and muscle tissues. Notably, even after gorging themselves, they still “save” significant nutrients for later arrivals.

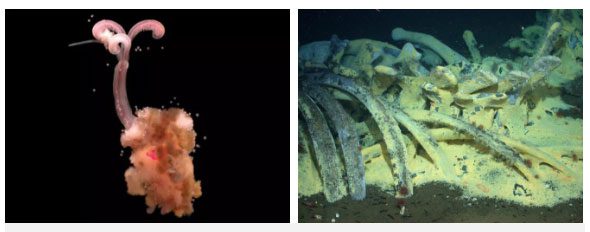

A Few Months Later: The Slimy Feast of Worms and Snails…

By this time, little flesh remains on the whale carcass. However, it will be covered by a rich layer of slimy microorganisms. This is also a food source for snails and various species of segmented worms.

Bristle worms.

For instance, bristle worms have survived five mass extinctions by finding food sources on animal carcasses.

A Few Years Later: A Feast of Bones for Microorganisms

When only the skeleton remains of a whale carcass, it still serves as a food source for microorganisms. There are some specific types of microorganisms that scientists have only found on whale carcasses.

Therefore, occasionally, scientists “sink” the carcasses of whales that have washed ashore to the ocean floor, so they can later collect microorganisms for research.

Zombie worms feeding on whale bones.

Additionally, the zombie worm (Osedax roseus)—a type of mollusk—specializes in consuming lipids from whale bones.

Decades Later: A Lifeline for Clams, Oysters, and More…

While the whale carcass is immense, over decades it transforms into thousands of small grains. However, these grains are rich in nutrients for bacteria at the ocean floor.

These bacteria cling to the shells of clams and oysters…

These bacteria attach themselves to the shells of clams and oysters… They help convert sulfur on the shells into sugars, providing sustenance for the mollusks inside.

Thus, indirectly, whale carcasses have nourished clams, oysters, and other shellfish on the ocean floor for decades!

What Happens If a Whale Dies Stranded?

However, not all whales sink to the depths of the ocean upon death.

Instead, some get stranded on beaches around the world. Although humans often attempt to rescue them, without water to maintain buoyancy, the weight of the whale’s own body will soon begin to crush its internal organs.

100 tons of decaying flesh from a beached whale is a “gold mine for science”—a fantastic opportunity for scientists to study a creature that is usually out of reach.