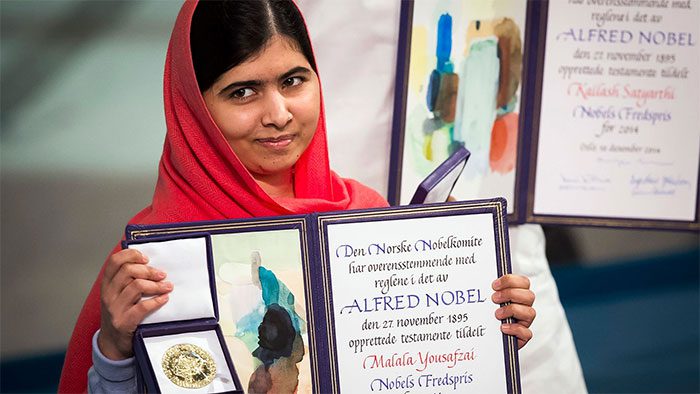

The Nobel Prize is an international award announced annually since 1901 to honor individuals who have achieved significant accomplishments in the fields of Physics, Chemistry, Medicine, Literature, and Peace; the Nobel Peace Prize can be awarded to individuals or organizations.

At around 5:45 PM on October 2, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced in Stockholm that the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine would be awarded to Katalin Karikó of the German biotechnology company BioNTech and Drew Weissman, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States, for their discoveries in developing effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19. This raises the total number of women who have received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to 13.

On the following day, October 3, the fifth woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics emerged. Anne L’Huillier, a female physicist from Lund University in Sweden, along with Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz from Ohio State University in the United States, jointly received the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering and innovative work in the science of ultrafast laser and attosecond physics.

Nobel Medal. (Illustrative image: CNN).

Statistically, the gender imbalance is quite pronounced. Compared to the Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine assessed by the Karolinska Institute, the awards in Physics and Chemistry evaluated by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences are even more of a “domain for male scientists.” Among the 224 previous winners, only 5 were women.

Even in the field of Physiology or Medicine, which has the highest number of female Nobel laureates, the ratio of male to female Nobel winners is still 16.5:1. Why are women so rare among Nobel Prize winners in science?

Male scientists often dominate Nobel Prizes. (Illustrative image: ZME).

The Gender Imbalance in Scientific Careers

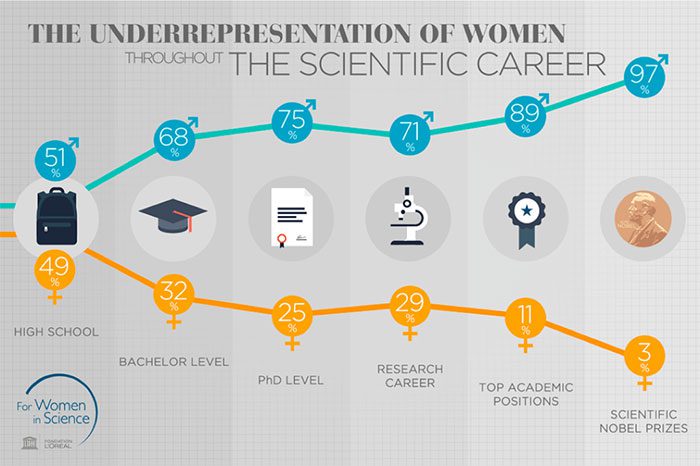

As early as 1975, Zuckerman and J. Cole, in their article “Women in American Science,” studied female scientists in the fields of Physics and Biology in the U.S. and pointed out that the gap between the number of men and women in these two groups would increase significantly as one progresses in rank (undergraduate – graduate – scientific researcher).

They provided explanations for this phenomenon:

- First, it results from the combined actions of social selection and self-selection;

- Second, the existence of limited differences, meaning in a community with limited resources and high competition for rewards. Consequently, a series of external factors affect scientists, where female scientists are more greatly impacted compared to their male counterparts, directly influencing the quantity and quality of scientific research outcomes.

Even decades later, Zuckerman’s research remains relevant. In 1994, the journal Science presented a set of statistics: “In the United States from 1992 to 1993, the proportion of women among assistant professors, associate professors, and professors was 42.3%, 28.9%, and 14.4%, respectively. Furthermore, a recent report by the Boston Consulting Group commissioned by the L’Oréal Foundation also showed that as one transitions to higher levels, the number of women declines more rapidly than men, indicating that women are more likely to give up and that achieving senior positions becomes increasingly difficult.”

In the United States, 29% of women participate in scientific research, 11% hold senior scientific research positions, and only 3% have won Nobel Prizes in Science. In contrast, 71% of men participate in scientific research, although 89% hold senior scientific research positions, 97% of men have won Nobel Prizes. Women clearly face disadvantages in advancing to senior scientific research positions. (Image: Digital-science).

Women in Society: The Impact of Gender Bias

In reality, society generally perceives that men must be more competitive and better suited for science, etc. These are all gender biases stemming from physiological differences between the sexes and social culture.

Starting from the family as a foundation, both men and women will be bound by gender biases. We know that the influence of family on personal development is mainly reflected in childhood, with personal character and future career choices closely linked to early family education. Analyzing the family circumstances of female Nobel laureates, we also see that most of them come from families with relatively high levels of understanding, decent economic conditions, and relatively open-minded thinking, which certainly has a positive impact on their lives.

However, on a broader scale, most families still unconsciously choose different methods when raising children. Research shows that many parents hope their sons will be active, lively, and eager to learn, while for daughters, they expect them to be gentler and more obedient. This restricts the freedom to explore the world for girls to a certain extent and is not conducive to nurturing curiosity about the world and science.

Female scientist. (Illustrative image: Zhihu).

The toys that children often encounter also have “gender” distinctions. While boys typically have more diverse and high-tech toys, such as toy airplanes, cars, puzzles, etc., girls’ toys are simpler, usually comprising dolls and storybooks. In shopping mall displays, toys for boys and girls are often placed separately, and the colors convey strong psychological meanings: boys’ toys are often bright-colored, while girls’ toys are predominantly pink. As a result, parents may unconsciously think that calm and open colors like blue and green are more suitable for boys. The choices made by parents will influence their children’s choices, and over time, boys and girls will develop similar gender biases as their parents.

The impact of this model continues. After entering school, there will be differences in the mindset regarding the upbringing of boys and girls, even though they seem to study the same subjects. However, in learning and activities, male students tend to gravitate toward the sciences to cultivate interests and practical abilities in Physics, Chemistry, etc. Even in textbooks, descriptions of men and women are biased: men appear to represent the social elite, while women are depicted more as housewives.

Gender bias stems from physiological differences between the sexes and social culture. (Illustrative image: Zhihu).

However, with the development of society, women have proven that they can achieve academic results that are certainly on par with those of men. This view has been supported by substantial data from developed countries in Europe and the United States. Numerous surveys in the U.S. have indicated that girls generally perform better than boys in school, and in recent years, the number of women obtaining science degrees has been steadily increasing, gradually reaching parity with men. As this trend becomes increasingly apparent, biases within families and schools are gradually changing, but their effects have yet to be completely eradicated.

Gender bias has created relatively common expectations for women’s roles. (Illustrative image: CNN).

The ratio of male to female Nobel Prize winners in Science varies greatly among their respective groups, which cannot be solely explained by the existence of gender discrimination in the scientific community but in fact has deeper causes.

From a societal perspective, gender bias has created relatively common expectations for women’s roles, which do not align with the preferences of the scientific community, thereby limiting women’s development within the scientific community. Childbearing also has a significant impact on women, leading them to often lower their expectations for scientific research, and at times even interrupt their scientific careers, causing many women to gradually drift away from the Nobel Prize.