In recent years, in-flight internet service through Wi-Fi connections has become increasingly popular. Have you ever wondered how Wi-Fi works on an airplane?

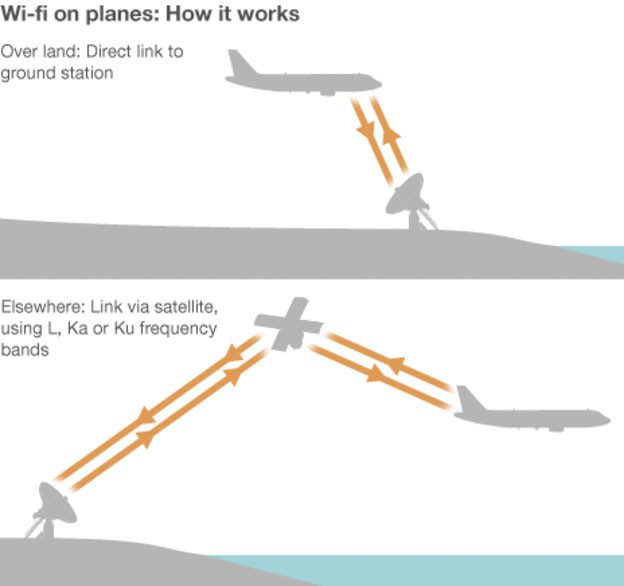

According to a former employee of a solution provider on Quora, there are two main methods to provide internet on airplanes: satellite signals and ground signals.

There are two ways for airplanes to connect to the internet: using ground signals (above) and satellite signals.

Ground signals are direct connections between the airplane and antennas on the ground. Numerous ground stations function similarly to mobile service BTS stations, but they are much larger. The antennas that receive signals are placed on the underside of the aircraft, and as the plane flies over different areas, it switches connections (handoff) between ground stations, just like a mobile phone. Users will not experience any noticeable delay during this handoff.

The downside of this technology is its relatively slow speed.

Setting up ground stations using this method is significantly cheaper than using satellites, but it has limitations regarding speed and geography. The current maximum speed, such as Gogo’s ATG4 service, is only 9.8 Mb/s shared among all passengers. At this speed, users can check emails or browse lightly, but streaming videos is difficult. Additionally, as ground stations are located on the ground, this method cannot be used for transcontinental flights. Ground signal internet is primarily applied to domestic flights within the United States, currently equipped on about 1,000 aircraft.

Satellite signals use orbiting satellites to provide internet service to airplanes. The satellites orbit approximately 16,000 km above the Earth, and signals are received through antennas located on the aircraft’s fuselage. Currently, the best solutions offer speeds of about 20 – 40 Mb/s per plane, depending on the number of aircraft using the satellite’s coverage. In the near future, Ka-band satellite signals may provide even higher speeds.

A technician is installing the satellite connection unit on a Boeing 747.

In addition to high speed, satellite signals are the only way to provide internet for flights over oceans. When flying, the antenna on the aircraft will automatically adjust its direction to connect to the satellite, and when the aircraft flies too far, it can switch to signals from another satellite.

However, the satellite signal method has two drawbacks. The first is higher latency due to the signal having to travel through a satellite at an altitude of over 10,000 km, and the process of connecting to another satellite will also affect the connection, unlike the seamless handoff between ground stations. The second drawback is the significantly higher cost, due to the high rental prices for satellites. This results in very high prices for in-flight internet.

On the aircraft, Wi-Fi access points (WAP) broadcast signals to users’ devices such as phones and laptops. The number of WAPs depends on the aircraft’s size, with larger planes potentially having up to 6 WAPs. Previously, when Wi-Fi was not common, some planes even had Ethernet ports for plugging in computers, but now Wi-Fi is sufficient for most users.

Despite significant advancements, there is still a considerable gap between in-flight Wi-Fi and ground-based Wi-Fi.

“The biggest difference for in-flight Wi-Fi is the complexity due to mobility factors. Airplanes typically travel at high speeds and over vast geographical areas, which require consistent coverage for a high-quality in-flight connection experience,” said Don Buchman, Vice President and General Manager of Commercial Aviation at Viasat, in an interview with CNN.

There is still a considerable gap between in-flight Wi-Fi and ground-based Wi-Fi. (Photo: Singapore Airlines).

Moreover, while satellite signals address some limitations faced by mobile phone towers, expanding the satellite network to keep pace with the growing demand is not always straightforward.

“In reality, deploying new mobile towers is much faster and cheaper than launching satellites on rockets,” disclosed Jeff Sare.

According to data from CNN, representatives from Delta and United airlines stated that they provide over 1.5 million in-flight Wi-Fi sessions each month, while JetBlue reported that their service is used by “millions of customers” annually.

However, with a market currently estimated at around $5 billion and projected to grow to over $12 billion by 2030, according to research firm Verified Market Research, there is still much potential for exploitation.

In a survey conducted by Intelsat last year involving airlines, service providers, and equipment manufacturers, 65% of respondents indicated that they expect the number of passengers desiring connectivity while flying to increase.

The two biggest barriers to increasing in-flight Wi-Fi usage, the survey indicated, are high service costs and “poor internet connectivity.”

To address these issues, service providers like Viasat, Intelsat, and Starlink plan to continue expanding their deployment capabilities by launching more satellites each year.

|

What is Wi-Fi? Simply put, Wi-Fi is a wireless internet connection network, which stands for Wireless Fidelity, using radio waves to transmit signals. This type of radio wave is similar to those used in mobile phones, television, and radio. Most electronic devices today, such as computers, laptops, smartphones, and tablets, can connect to Wi-Fi. How Wi-Fi Networks Work To establish a Wi-Fi connection, a Router (transceiver) is necessary. This Router obtains information from the internet through a wired connection and converts it into a wireless signal to be transmitted. The wireless signal adapter on mobile devices receives this signal and decodes it into necessary data. This process can work in reverse as well, where the Router receives wireless signals from the Adapter, decodes them, and sends them through the internet. |