Wireless networks are one of the greatest advances in the computer industry. Last year, tens of millions of Wi-Fi devices were sold, and it is forecasted that this year there will be around 100 million users. The development journey of this technology from a narrow scale to a wide range has only just begun about five years ago.

Wireless networks are one of the greatest advances in the computer industry. Last year, tens of millions of Wi-Fi devices were sold, and it is forecasted that this year there will be around 100 million users. The development journey of this technology from a narrow scale to a wide range has only just begun about five years ago.

The Beginning

In 1985, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) decided to “open up” several frequency bands of wireless spectrum, allowing their use without government licensing. This was quite unusual at the time. However, persuaded by technical experts, the FCC agreed to release three bands designated for industrial, scientific, and medical purposes for telecommunications businesses.

These three bands, known as “junk bands” (900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, 5.8 GHz), were allocated for devices used for non-communication purposes, such as microwave ovens that use radio waves to heat food. The FCC allowed these bands to be used for communication on the condition that any device using these frequencies must operate in a way that avoids interference from other devices. This was achieved through technology known as spread spectrum (originally developed for U.S. military use), which can transmit radio signals across a wide range of frequencies, unlike the traditional method of sending signals on a single predetermined frequency.

Merging Standards

A significant milestone for Wi-Fi occurred in 1985 when the process of establishing a common standard was initiated. Prior to this, wireless LAN device providers like Proxim and Symbol in the U.S. developed proprietary products, meaning that devices from one company could not communicate with those from another. Thanks to the success of wired Ethernet networks, some companies began to realize that establishing a common wireless standard was crucial. Consumers would be more willing to adopt new technology if they were not limited to the products and services of a specific company.

In 1988, the NCR Corporation, wanting to use the “junk” band to connect ATMs wirelessly, tasked an engineer named Victor Hayes to explore establishing a common standard. He, along with expert Bruce Tuch from Bell Labs, approached the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), where a subcommittee named 802.3 had established the now-popular Ethernet local area network standard. A new subcommittee called 802.11 was formed, and the process of negotiating the merger of standards began.

The fragmented market at that time meant it took considerable time for different product providers to agree on standard definitions and develop a new criterion with the approval of at least 75% of subcommittee members. Finally, in 1997, this subcommittee approved a basic set of criteria that allowed data transmission rates of 2 Mb/s, using one of two spread spectrum technologies: frequency hopping (which avoids interference by continuously switching between radio frequencies) or direct-sequence transmission (which sends signals across a range of frequencies).

The new standard was officially issued in 1997, and engineers immediately began working on prototype devices compatible with it. Subsequently, two versions of the standard, 802.11b (operating on the 2.4 GHz band) and 802.11a (operating on the 5.8 GHz band), were approved in December 1999 and January 2000, respectively. After the 802.11b standard was established, companies began to develop devices compatible with it. However, this standard was lengthy and complex, spanning 400 pages, and compatibility issues remained prominent. Therefore, in August 1999, six companies including Intersil, 3Com, Nokia, Aironet (later acquired by Cisco), Symbol, and Lucent teamed up to form the Wireless Ethernet Compatibility Alliance (WECA).

Finding an Appropriate Name

The mission of the WECA organization was to certify that products from different suppliers were genuinely compatible with each other. However, terms like “WECA-compatible” or “IEEE 802.11b compliant” still caused confusion within the community. The new technology needed a user-friendly name for consumers. Experts suggested several names like “FlankSpeed” or “DragonFly.” Ultimately, the term “Wi-Fi” was accepted as it sounded like a high-quality technology (hi-fi) and consumers were already familiar with the concept that CD players from one company could be compatible with amplifiers from another. Thus, the name Wi-Fi was born. The explanation that “Wi-Fi means wireless fidelity” was later concocted. Recently, many experts have also written articles asserting that Wi-Fi is simply a name created for convenience without any original meaning.

Becoming Part of Everyday Life

Thus, the technology for wireless local area networks was standardized, with a unified name, and it was time for a champion to promote it in the market. Wi-Fi found its champion in Apple, the computer manufacturer known for its groundbreaking innovations. The “Apple” company announced that if Lucent could produce an adapter for under $100, they could integrate a Wi-Fi slot into every laptop. Lucent met this challenge, and in July 1999, Apple announced the introduction of Wi-Fi as an option on its new iBook line of computers, using the AirPort brand. This completely transformed the wireless networking market. Other computer manufacturers quickly followed suit. Wi-Fi rapidly reached household consumers, especially as spending on technology in businesses was limited in 2001.

Wi-Fi continued to gain momentum due to the strong rise of high-speed broadband Internet connections in households, becoming the easiest way for multiple computers to share a broadband connection. As this technology expanded, fee-based access points known as hotspots began to proliferate in public places such as stores, hotels, and cafes. Meanwhile, the FCC once again modified its regulations to permit a new version of Wi-Fi called 802.11g, using more advanced spread spectrum techniques known as Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing (OFDM), capable of achieving speeds of up to 54 Mb/s on the 2.4 GHz band.

The Road Ahead

The Wi-Fi enthusiasts believe that this technology will overshadow all other wireless connection methods. For example, they argue that hotspots will compete with 3G mobile networks, which promise high-speed data transmission capabilities. However, such reasoning has been exaggerated. Wi-Fi is merely a short-range technology and will never provide the extensive coverage that mobile networks can, especially as these networks continue to grow significantly in scale due to roaming services and international billing agreements.

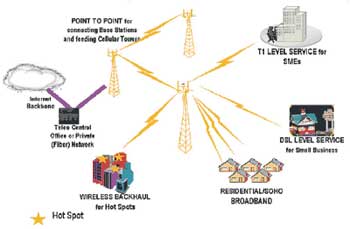

However, in just a few years, the first generation of networks based on the new WiMax technology, also known as 802.16, will emerge and become widespread. As the name suggests, WiMax is the wide-area version of Wi-Fi, with a maximum throughput of up to 70 Mb/s and a range of up to 50 km, compared to Wi-Fi’s current range of 50 m. Additionally, while Wi-Fi allows access only in fixed locations with hotspot devices (similar to public telephone booths), WiMax can cover an entire city or multiple provinces like mobile phone networks.

Currently, Wi-Fi is the dominant networking technology in households in developed countries. TVs, DVD players, recorders, and many Wi-Fi-capable consumer electronics are increasingly becoming commonplace. This allows users to transmit content across devices in the home without wires. Wireless phones using Wi-Fi networks are also present in offices, but in the long run, this wireless access technology seems unlikely to win in the long-term race for these devices. Currently, Wi-Fi consumes considerable energy from handheld devices, and even the 802.11g standard cannot stably support more than one video stream. Therefore, a new standard called 802.15.3, or WiMedia, has been promoted to become the short-range standard for high-speed home networks, primarily serving entertainment devices.

The development of Wi-Fi technology has also demonstrated that unifying to create a common standard can create a new market. This is further affirmed by the determination of companies promoting the WiMax standard. Previously, long-range wireless network technologies were all manipulated by large companies with proprietary standards that were not widely accepted. Thanks to the success of Wi-Fi, these “giants” have now collaborated to develop WiMax, a consumer-friendly standard that companies hope will expand the market and increase revenue. While the future of Wi-Fi is hard to predict, it has undoubtedly paved the way for many other technologies.