According to recent studies, prehistoric women not only frequently participated in hunting but also had physiological advantages for this activity compared to men.

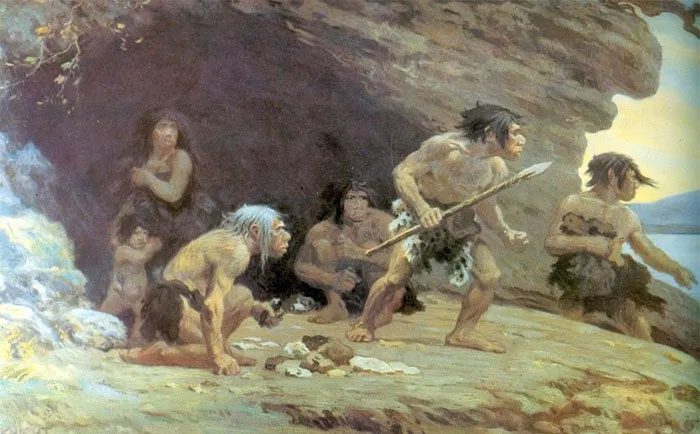

As a child, Cara Ocobock often wondered about the images of prehistoric people depicted on TV, in books, comics, and cartoons: “men hunting” with spears in hand, “women gathering” with a baby strapped to their back and a basket of seeds in hand.

“That’s the image people commonly see, an assumption we all have in our heads, and it’s been presented in natural history museums” – Ocobock shared.

Many years later, Ocobock became an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. While researching human physiology and prehistoric evidence, she discovered that many assumptions about prehistoric men and women are not entirely accurate. To date, the evolutionary perspective that men are biologically superior to women remains accepted; however, this interpretation does not tell the whole story.

Together with her colleague Sarah Lacy, an anthropologist at the University of Delaware, Ocobock published two studies in the American Anthropologist journal in November 2023. Discussing their research, Ocobock stated: “Rather than viewing this as a way to erase or rewrite history, our studies simply aim to amend the historical narrative that has removed women’s roles from it“.

Familiar illustrations of prehistoric times: men hunting and doing dangerous jobs while women handle lighter tasks. (Photo: Internet).

Hormones – The “Unsung Heroes”

In their physiologic-focused research, the two researchers explain that prehistoric women were fully capable of performing physically demanding tasks such as hunting large game and could successfully hunt over extended periods. From a metabolic perspective, Ocobock notes that women’s bodies are suited for endurance activities, “this factor plays a crucial role in prehistoric hunting, as they would need to tire out their prey before actually killing it“.

Two significant factors that enhance metabolic processes are estrogen and adiponectin, which are typically found in higher quantities in female bodies. These hormones are essential for helping women’s bodies regulate glucose and fat – a critical function for athletic activities.

Specifically, estrogen helps regulate fat metabolism by encouraging the body to use stored fat for energy before depleting stored carbohydrates. Ocobock explains: “Since fat contains more calories than carbs, it burns longer and slower, meaning it’s a type of stored energy that can help us perform longer and delay fatigue”.

Estrogen also protects cells in the body from damage caused by high temperatures during physical activity. “For me, estrogen is truly an unsung hero of life” – Ocobock stated – “It’s vital for cardiovascular health, metabolism, brain development, and injury recovery”.

The hormone adiponectin also enhances fat metabolism while simultaneously limiting carbohydrate and/or protein metabolism, allowing the body to maintain activity for longer periods, especially over long distances. In this way, adiponectin can protect muscles from weakening, allowing for sustained activity.

According to Ocobock and Lacy, the very bodily structure of prehistoric women provided inherent advantages in endurance and efficiency for hunting tasks. “Women generally have wider hip structures, allowing them to rotate their hips and extend their strides. The longer the stride, the less metabolic activity occurs, enabling you to travel farther and faster” – Ocobock explains.

“If we look at human physiology this way, we can consider women as marathon runners and men as weightlifters.”

A mosaic depicting the moon goddess and hunting Artemis from Greek mythology. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Archaeology Unveils More About “Female Hunters”

Some archaeological findings show that prehistoric women not only sustained injuries from dangerous close-range hunting (similar to men) but also valued and esteemed this activity.

“We reconstructed the hunting activities of Neanderthals as individual hunting at close range, meaning the hunter often had to sneak up on their prey before killing them” – Ocobock noted, “When examining the fossil records of prehistoric people, we found that both women and men had similar injuries.”

Ocobock describes these injuries as comparable to those experienced by modern rodeo clowns – head and chest injuries from being kicked by animals; limb injuries from bites or fractures. “We found that the types and rates of injuries in women and men were equal”, she said, “Thus, both genders participated in large-scale ambush hunting activities.”

Furthermore, there is evidence of female hunters during the Holocene in Peru, where women were buried with hunting weapons. “Typically, people are not buried with something unless it holds significant meaning to them or was something they used frequently while alive.”

“Moreover, we have no basis to believe that prehistoric women abandoned hunting when they became pregnant, breastfed, or carried children” – Ocobock added, “We also do not see any signs in ancient history indicating the existence of gendered labor division.”

According to Ocobock, in prehistoric societies, survival was a collective effort. “Groups did not have enough individuals to assign separate tasks to each person. Everyone had to possess general skills to survive.”

Through these studies, the authors hope to encourage a shift in long-held beliefs that women are physically weaker than men.

Ocobock believes that the scientific community must be extremely cautious about how contemporary biases can influence our understanding of the past.

“We cannot immediately assume someone’s abilities based solely on the gender we categorize them into after observing them” – Ocobock concluded.