For many decades, the Egyptian pyramids have revealed numerous details about the lives of the pharaohs in ancient Egyptian society. However, for a long time, little attention has been given to the lives of those who toiled, shedding sweat, tears, and blood to create these monumental architectural works.

For many decades, the Egyptian pyramids have revealed numerous details about the lives of the pharaohs in ancient Egyptian society. However, for a long time, little attention has been given to the lives of those who toiled, shedding sweat, tears, and blood to create these monumental architectural works.

These were the workers from all over Egypt, participating in construction sites; recently, through archaeological discoveries analyzed with modern technology, we have begun to learn more about their lives.

For a long time, when discussing the Egyptian pyramids, aside from the unresolved mysteries surrounding the pharaohs, researchers have often been haunted by questions related to the individuals who directly built them: What social class were they? Where did they live before and during the construction of the pyramids? What was the daily life of a construction worker and their families like?

The first hypotheses aimed at answering some of these questions were proposed in 1888, during an archaeological investigation by British scientist Flinders Petrie at the pyramid complex of Senwosret II in Ilahun. Here, a walled area revealed images of a town with high foundation houses, walls made of mud bricks, containing manuscripts written on papyrus, pottery, tools, clothing, and children’s toys,  along with all the fragments of daily life that were absent in previous archaeological excavation sites. The first Egyptologists in the history of archaeology did not devote time to studying and understanding the civil architecture of ancient Egypt. Only recently, thanks to extensive excavations by two Egyptologists, Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass, around the Great Pyramid area, has some information about the lives of the pyramid builders there come to light.

along with all the fragments of daily life that were absent in previous archaeological excavation sites. The first Egyptologists in the history of archaeology did not devote time to studying and understanding the civil architecture of ancient Egypt. Only recently, thanks to extensive excavations by two Egyptologists, Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass, around the Great Pyramid area, has some information about the lives of the pyramid builders there come to light.

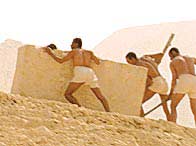

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, the Great Pyramid was built by 100,000 slaves who worked continuously, with groups being replaced every three months. However, current researchers consider this a misunderstanding by Herodotus. Pharaoh Khufu, who ruled Egypt during the Fourth Dynasty — the dynasty responsible for constructing the Great Pyramid — could not have such a massive workforce at his disposal. Moreover, even if he had such a number, it would be impossible for 100,000 people to work on a pyramid simultaneously. Each archaeologist has their own calculations regarding the number of workers involved in this project, but most agree that the Great Pyramid was built by nearly 4,000 skilled workers, such as stone masons, transport workers, and bricklayers, with the assistance of about 16,000 to 20,000 laborers responsible for ramp construction, mixing mortar, providing food, clothing, fuel, etc. Thus, the total number of people participating in building the Great Pyramid is estimated to be around 20,000 to 25,000, working over 20 years or even longer.

Researchers estimate that the workers were divided into two groups: a permanent workforce of about 5,000 people, who lived with their wives and other relatives in a well-organized village, and a temporary workforce of 20,000 people, who worked in shifts of three or four months, living in less organized camps along the pyramid village. Today, a massive limestone wall has been found separating the living area from the “realm of the dead.” The main village of the pyramid builders is located outside this wall, close to the pyramid temple. Unfortunately, most of this village now lies beneath the modern town of Nazlet-es-Samman, making access difficult.

Today, archaeologists have discovered a gently sloping cemetery where men, women, and children from the pyramid village were buried. Their graves are quite diverse, with some shaped like small pyramids, others like stepped pyramids, and some being vaulted tombs, often made from the precious stones “borrowed” from the main pyramid construction materials. Larger limestone graves located at the high point of the cemetery slope were reserved for those responsible for overseeing the construction and supplying materials. In the past, pyramid robbers did not pay attention to such cemeteries, so many skeletons remain intact today, allowing scientists to reconstruct the lives of those who lived, worked, and died at Giza.

Among the 600 skeletons surveyed in the pyramid cemetery, nearly 50% were women, and the number of children and infants accounted for about 23% of the total. This easily leads to the conclusion that during the construction of the pyramids, the main workers lived with their families right under the shadow of the massive tombs dedicated to the pharaohs.

In the tombs of the supervisors, inscriptions describe the organization and supervision of the workforce. These texts provide us with insights into the pyramid construction system. They show that the use of temporary labor was a typical solution for the Egyptians concerning logistics. At the Giza pyramid complex, the workforce was divided into groups of 2,000 people and further subdivided into smaller groups of 1,000, 200, and finally down to groups of 20.

The temporary workers at the pyramid construction site lived in makeshift camps next to the town. Here, they were paid in the form of food rations. The standard under the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BC) for a worker was 10 loaves of bread and a jug of beer per day.

Supervising officials and those with higher status received hundreds of loaves of bread and many jugs of beer each day. These foods could not be stored for long, suggesting that they were sold on the market in exchange for other products or money. In any case, a pyramid town, like any other Egyptian town, would soon develop its own economy.

Supervising officials and those with higher status received hundreds of loaves of bread and many jugs of beer each day. These foods could not be stored for long, suggesting that they were sold on the market in exchange for other products or money. In any case, a pyramid town, like any other Egyptian town, would soon develop its own economy.

Temporary workers who died at the work site were buried with the tools they had acquired. In surveys, archaeologists have noted that their graves were hastily buried and appeared poorer compared to those of permanent workers. To the south of the pyramid town, an industrial area was discovered, divided into multiple blocks or corridors separated by stone-paved roads equipped with drainage systems, and even some houses for workers. Mark Lehner discovered a copper production factory, two bakeries capable of baking hundreds of loaves of bread at once, and a fish processing facility with remnants of thousands of fish. This represents a large amount of food intended for many people, although Lehner has yet to find evidence of any storage facilities or places to store tools and food. Animal bones found in the pyramid town and nearby areas came from species such as ducks, sheep, and pigs. They could have been raised domestically within the workers’ workshops in the pyramid town, but higher-grade livestock like cattle might have been raised in expansive pastures and transported to the town.

After comparing DNA samples extracted from the remains of pyramid construction workers with samples taken from contemporary Egyptian residents, Dr. Mopamia from Cairo University hypothesized that the Khufu pyramid was a national-scale project, with workers coming from all over Egypt. Of course, this female scientist found no traces of aliens or even extraterrestrial beings, as many tales have suggested. In reality, the pyramids served as both a massive training project and a source of “Egyptianization.” Workers left communities of only 50 or 100 people to live and work in a town with 15,000 or more inhabitants. They returned to their hometowns with new skills, a broader perspective, and a renewed sense of nationhood. Paying them, even in the form of food rations, was also a form of national income redistribution.

It can be said that in ancient Egypt, most families were directly or indirectly involved in the construction of the pyramids. However, contrary to Herodotus’s hypothesis that they were oppressed slaves, Lehner and Hawass suggest that they might have been volunteers. Hawass believes that the pyramid symbol possessed enough spiritual strength to inspire volunteers for the national good. Mark Lehner went further, comparing pyramid construction to establishing grain storage for the Amish community in the U.S., based on the spirit of volunteerism. Is this a new discovery related to the labor system of those involved in building the great works of Egypt in particular and humanity in general?