Have you ever wondered: what is the roundest object? Check out the video below to find out!

The silicon spheres used to define the kilogram are so smooth that if they were scaled up to the size of Earth, the highest and lowest points would be only a few meters apart.

Scattered across facilities far apart in Australia, the United States, Germany, Japan, and more, is a collection of 7 meticulously polished and strictly protected spheres. These are the silicon spheres of the International Avogadro Project. They were crafted at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia with extreme precision and are considered the roundest objects in the world.

![]()

A silicon sphere similar to those used in measuring Avogadro’s constant. (Photo: NIST).

The surfaces of these spheres are so smooth that if enlarged to the size of Earth, the distance between the highest mountain and the deepest ocean would only be 3 – 5 meters, according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), one of the organizations involved in the International Avogadro Project. Optical interferometers have enabled researchers to measure the width of the spheres with accuracy down to the nanometer. Each sphere costs about $3.2 million, handcrafted by skilled lens makers.

So, what is the purpose of creating these spheres? The International Avogadro Project aims to use these perfect silicon spheres to accurately determine the value of Avogadro’s constant (a fundamental physical constant), as stated by the Powerhouse Museum, which has preserved a prototype sphere since 2016. Specifically, the goal is to redefine the kilogram based on Avogadro’s constant.

Going back to the 18th century, when the metric system was established, the first definitions were based on the natural world. A meter is defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator, measured along a straight line through Paris. A liter is the volume of 1/1,000 m3 of water, measured at the melting point of ice. A kilogram is the mass of that amount of water in a vacuum.

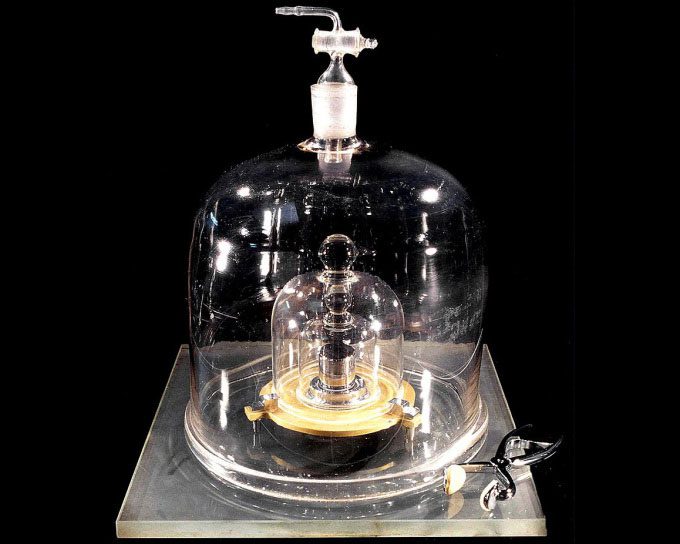

After these definitions were proposed, the French Academy of Sciences began to formalize them. In 1799, they used physical objects to illustrate the measurement units, including a cylinder weighing one kilogram known as Le Grand K or Big K.

The Le Grand K mass is preserved in Paris. (Photo: BIPM)

Over time, these measurements became widely accepted globally. However, a serious issue arose as they were entirely based on physical objects. The circumference of the Earth seemed like a constant to those who established this system, but in reality, it continuously changes. In fact, the system was flawed from the start because the scientists responsible for calculating lengths miscalculated by 0.2 mm, and no one corrected the final figure.

Due to this and other reasons, in the 20th century, there was a push to redefine units based on more accurate natural constants. Among them, the mole – the unit used to measure the amount of substance – was established as the amount of substance containing 6.02214076 x 1023 elementary entities, known as Avogadro’s constant.

In 2005, at the 94th meeting of the International Committee for Weights and Measures, experts recommended that the kilogram should be redefined based on a universal constant. The committee decided that the best choice was to use Planck’s constant.

However, some scientists had a different idea. Since the current definition of Avogadro’s constant depends on the mass of a substance, they suggested that this relationship could be exploited in reverse. But first, they needed to define this constant with higher accuracy – with a relative error of only 20 parts per billion – so that the new kilogram definition based on Avogadro’s constant could compete in precision and reliability with the current standard.

The basic plan was to create an object from a precisely measured amount of a well-known substance and then define the kilogram accordingly. This object is precisely the silicon spheres, which offer many advantages over Big K. Even if the silicon spheres are lost or damaged, it would not affect the definition of the kilogram, since the kilogram is defined not by a physical object but by a concept.

When the definition of an international standard base unit depends on counting the number of atoms in an object, the calculations must be extremely precise. That is why the spheres must be so round. “The sphere was chosen as the ideal shape because it has no edges or corners (avoiding chipping or wear), and if a sphere is made perfectly, its volume can be calculated from a single parameter (diameter),” explains the Powerhouse Museum.

Meanwhile, silicon was selected because there are established processes for producing and manipulating silicon of extremely high purity. Silicon also offers many advantages for scientists: they know the mass of the silicon-28 isotope and the spatial parameters of the crystal lattice have been standardized, facilitating calculations of the number of atoms within the sphere.

Although the International Committee for Weights and Measures has chosen Planck’s constant as the basis for redefining the kilogram, other natural constants could also be used, at least to help verify the accuracy of the definition based on Planck’s constant, according to NIST.