If humans were not to shear sheep, how would they manage their wool? This brings to mind the story of a sheep rescued with an enormous fleece; had it not been rescued in time, it would have died. This led me to further explore whether sheep can shed their wool naturally or if they are dependent on humans for shearing.

In December 2015, in Canberra, Australia, a sheep named Chris went missing, and when discovered by a hiker, its fleece was so large that it covered its eyes. Chris was quickly sheared, and the fleece weighed a staggering 40 kilograms. It took 45 minutes to remove the fleece from Chris, whereas the usual shearing process takes about 30 seconds. So why didn’t Chris shed its wool naturally and instead endured such a massive fleece?

Chris was a Merino sheep, a breed specifically raised for wool, known for its soft fleece. Merino sheep are economically valuable and are widely raised in Europe and Australia.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Spanish shepherds crossbred local sheep with British breeds, resulting in the Merino breed, which is not suited for survival in the wild. This breed cannot shed its wool annually, a vital survival trait for sheep in nature, making Merino sheep entirely dependent on humans. They require shearing, producing between 4.5 to 20 kilograms of wool each year.

Being a Merino sheep, Chris faced severe issues: it had been lost in the wild for five years, and its fleece continued to grow. While this is what farmers desire, it is a disaster for the sheep. An unshorn, thick fleece can lead a Merino sheep like Chris to face serious health risks, including disease or even complications with basic functions like urination.

Cases of Merino sheep lost in the wild are not uncommon; in 2004, a sheep named Shrek was found living alone in a cave in New Zealand for six years, with a fleece weighing 27 kilograms.

So, the sheep we see with their fluffy and amusing coats are actually Merino sheep, a breed specifically developed for wool, a product of human intervention. It’s likely that the silly sheep in “Shaun the Sheep” are also of the Merino breed.

What about other sheep? Can they shed their wool naturally, or do they also require human assistance?

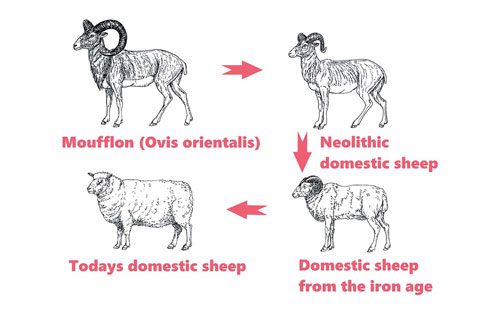

Sheep have been domesticated by humans for about 11,000 to 9,000 years BC, originating from the wild Mouflon sheep in Mesopotamia—a region in Western Asia that includes present-day Iraq, Kuwait, eastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, and areas along the Turkey-Syria and Iran-Iraq borders. Sheep were among the first animals to be domesticated. The Persians raised sheep for meat, milk, and hides, and around 6,000 years ago, they began raising sheep for wool. Humans started harvesting sheep wool for survival, which helped keep them warm through harsh winters. Plant fibers were not warm or water-resistant, and animal skins were neither soft nor particularly insulating. Wool from sheep became an integral part of Persian culture and a distinctive commercial product. From there, sheep wool began to be exported to Africa and Europe, becoming a crucial fiber for humans, as it is natural, reusable, and biodegradable.

Before the advent of modern machinery for shearing wool, earlier methods involved “pulling” wool by hand or collecting wool that naturally shed in the fields. Since then, humans have bred many sheep varieties for various purposes, including wool production, meat, and milk.

Most wool-producing breeds are primarily suited for farm environments, as they have been bred to have fleece that grows year-round—meaning they cannot survive without human intervention. Each sheep breed has different fleece characteristics to produce various types of wool. In addition to Merino, there are many breeds specialized for wool production, such as Romney sheep, Lincoln sheep which have the longest and heaviest fleece for spinning and weaving (as shown above), Teeswater sheep with long fibers of large diameter, long-haired Leicester sheep, and Corriedale sheep, a hybrid between Merino and Lincoln.

Only a few primitive sheep breeds still retain their natural wool-shedding characteristics and are still being raised. Notable examples include semi-wild Scottish breeds like Boreray sheep, primarily raised for meat, which shed naturally, and Soay sheep, known for their distinctive dark fleece that can shed naturally (as shown above).

In addition, many sheep breeds have been bred solely for meat and milk, leading to less wool development compared to Merino sheep. For example, short-haired Katahdin sheep originated in Maine, USA, Dorper sheep from South Africa, Blackbelly sheep related to wild mountain sheep found in the Mediterranean basin, small Croix sheep, and the popular Persian Blackhead sheep found in Africa, along with many other African breeds with short, soft wool adapted to their environments, such as West African Dwarf sheep and Maasai Red sheep.

In summary, sheep have coexisted closely with humans for a long time, and for those sheep raised primarily for wool, please do not wander off! Without human shearing, they might not even be able to relieve themselves. Chris, the sheep with a 40-kilogram fleece, set the world record for “The Heaviest Wool Fleece Shorn from a Sheep.” Sadly, Chris passed away in October last year, just shy of 10 years old. People remember Chris as a resilient sheep who lived alone among kangaroos with a fleece nearly double its body weight for five continuous years.