Genetic studies can unveil many secrets buried over time, from our ancestral origins to historical pandemics. In this case, research has revealed that around 7,000 years ago, men were nearly driven to extinction.

The reason is the “Y-chromosome bottleneck phenomenon.” This phenomenon occurred at a certain point during the Stone Age when genetic diversity suddenly halted, at least among male genetic lines. After approximately 2,000 years of continuous decline, only one man remained for every 17 women.

Around 7,000 years ago, men were nearly driven to extinction.

Previously, scholars believed this could be related to our ancestors exploring and settling in new lands. They referred to it as the “founder effect,” where small groups of individuals continuously moved to explore new territories.

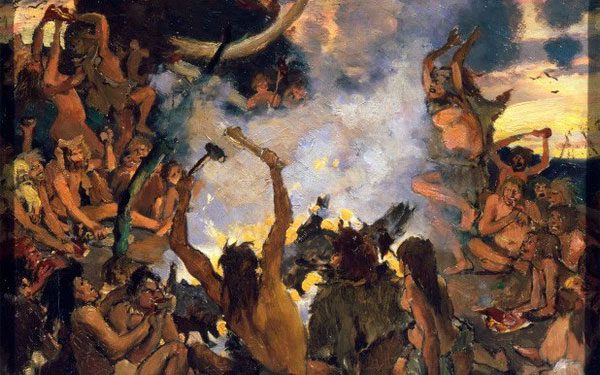

However, a new study published in the scientific journal Nature has uncovered a much harsher reality. Men of that time were killing each other.

The number of men in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East significantly declined due to this phenomenon around 5,000 to 7,000 years ago. The Y-chromosome from fathers passed on to sons is the reason nearly entire families were wiped out on a large scale. At one point, the world’s population was estimated to be only between 5 to 20 million, with over 9.5 million men killed.

But why?

A research team from Stanford University suggests the reason is “competition among kin groups.” The team created 18 computer simulation models, each with different scenarios explaining the decrease in male population, including factors such as Y-chromosome mutations, competition among clans, and mortality rates.

The results indicated that warfare among patrilineal clans led many men to die before they could reproduce, thus diminishing genetic diversity. And since patrilineal clans shared similar Y-chromosomes, if one clan wiped out another, it meant that Y-chromosome could hardly be passed on to future generations.

Warfare among patrilineal clans led many men to die.

Moreover, after these conflicts, the number of women often exceeded that of men. Marcus Feldman – a research author at Stanford University – stated: “Within the same patrilineal clan, women could come from anywhere. They might be from another clan that was defeated in battle or women who previously lived in that area.”

Essentially, victorious clans would eliminate the men of their opponents to ensure ongoing dominance and eliminate potential competition. They would then capture the surviving women. “If you look at the history of colonization, you will see that people often killed all the men and kept the women for themselves.”

Chris Tyler Smith – an evolutionary geneticist at the Sanger Institute (UK) – remarked: “The researchers at Stanford conducted careful computer simulations before reaching their conclusions. The hypothesis that ancient warfare caused the Y-chromosome bottleneck is very plausible, especially during the Neolithic period.”

Humans were still living in small-scale agricultural clans 5,000 to 7,000 years ago. Later, they transitioned to larger social groups and built large cities. During this period, the male population gradually recovered. “It was the transition from stone tools to metal tools in agriculture,” Tyler-Smith said.

The Stanford research team stated: “Our research findings are substantiated by archaeological discoveries alongside anthropological theories.”

Evidence of wars during the Neolithic period can be found in fossilized skeletons across Europe, including England. Many skeletons show signs of being attacked by arrows, clubs, and stone axes – weapons used by humans of that time.

Marta Mirazón Lahr, an anthropologist at the University of Cambridge (UK), noted that: “The fossils indicate these individuals – who lived by hunting and gathering – were massacred in a deliberate attack by raiders from other regions.”