According to ancient beliefs, salt is a valuable item representing the supreme beings. In fact, this idea originates from salt’s ability to preserve and embalm.

Salt has preservative properties. Even in modern times, it remains a primary method for food preservation. The Egyptians used salt for embalming. This preservative effect, which prevents decay, has given salt a metaphorical significance worldwide. Perhaps this is what Freud deemed irrational, as subconsciously we associate a mundane substance like salt with profound meanings such as immortality and eternity.

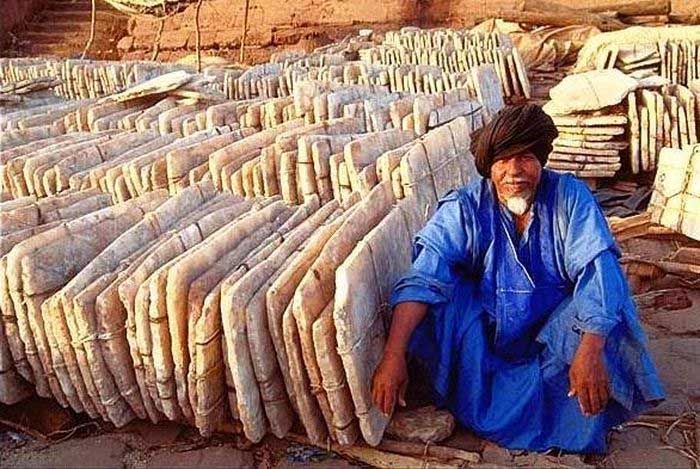

A salt trader in Africa, where salt is still highly valued. (Photo: Finances).

For the ancient Jews, salt was a symbol of the eternal covenant between God and the people of Israel. The Torah, in Numbers, recounts: “It is a covenant of salt forever before the Lord.” Later, Chronicles states that, “The Lord, the God of Israel, has given the kingdom of Israel to David and his descendants forever by a covenant of salt that cannot be broken.”

On Friday evenings, Jews often dip their Sabbath bread into salt. In Judaism, bread symbolizes sustenance and is a gift from God; dipping bread in salt serves to preserve it, which is also synonymous with maintaining the covenant between God and His people.

Faithfulness and friendship are linked to salt due to its enduring nature. Even when dissolved in liquid, brine can evaporate and condense back into square salt crystals. Because of this immutable characteristic, in both Islam and Judaism, salt is used to seal agreements. The Indian army pledged loyalty to the British with salt. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans used salt in sacrifices and offerings, invoking the gods with salt and water.

Not only associated with eternity and permanence, in Christianity, salt is also linked to truth and wisdom. The Catholic Church dispenses both holy water and holy salt, known as Sal Sapientia, “Salt of Wisdom.”

Bread and salt, one representing blessing and the other symbolizing unchanging permanence, are often linked together. Bringing bread and salt into a new home is a Jewish tradition dating back to the Middle Ages. The English do not bring bread but have a custom of bringing salt into a new house for centuries. In 1789, when Robert Burns (the Scottish bard) moved to a new house in Ellisland, he was sent off by relatives with a bowl of salt. The city of Hamburg (Germany) hosts an annual blessing festival, parading through the streets with chocolate-covered bread and almond pastries coated in salt.

According to Welsh tradition, at funerals, a plate of bread and salt is often placed on the coffin, and a local “professional eater of sins” is invited to consume the salt.

Since salt prevents decay, it is believed to protect individuals from harmful influences. In the early Middle Ages, Northern European farmers learned to protect their harvested grains from ergot (a harmful fungus) by soaking the grains in brine. Thus, it is not surprising that Anglo-Saxon farmers added salt to the sacrificial offerings to pray for bountiful harvests.

Both Jews and Muslims believe that salt can protect individuals from the evil eye. The book of Ezekiel mentions that rubbing salt on newborns will protect them from demons. In Europe, the tradition of protecting infants by placing salt on their tongues or soaking them in brine is thought to have originated from the Christian baptism ceremony. In France, soaking infants in salt until they are baptized remained common until 1408 when this practice was abolished.

Salt is a powerful substance that can sometimes be dangerous and must be handled with care. The dining etiquette of medieval Europe particularly emphasized how to scoop salt: it should be scooped with the knife’s tip and never touched with hands. Some ancient Jews believed that if a person used their thumb to serve salt, their children would die; if they used their little finger, they would become poor, and if they used their index finger, they would become a murderer.