In a sophisticated mechanism of evolution, this virus strain has taken control of the host’s brain, leading it to engage in life-threatening behavior.

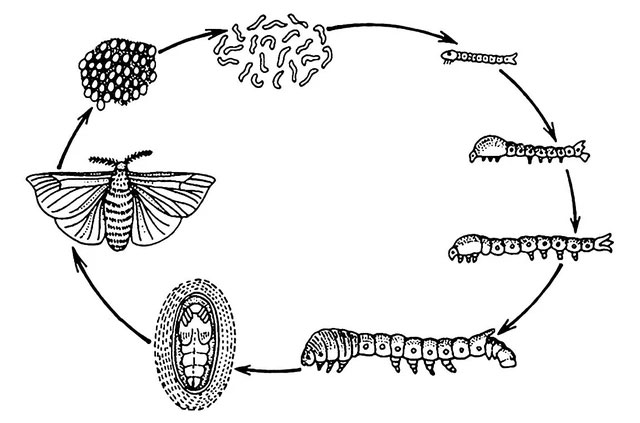

This is the profile of the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera), the main character in our story today. Like many other moth species, the cotton bollworm undergoes a life cycle to mature, starting from an egg, developing into a larva, then a pupa, and finally becoming a moth.

Cotton bollworm.

The cotton bollworm must undergo a life cycle to mature.

The cotton bollworm is in its larval stage during this time. Its task is to focus on eating as many leaves as possible, filling its belly to prepare for burrowing into the ground, where it will sleep and wait to transform into a pupa. However, scientists have observed a rather strange phenomenon:

Some cotton bollworms refuse to eat, and when the time comes to burrow into the ground to pupate, they do not crawl down. Instead, the cotton bollworm climbs high into the treetops and writhes there as if it were “high“.

This is an extremely risky behavior for the cotton bollworm. While they are not easily knocked down, “dancing” at the top of the tree means the cotton bollworm is inviting birds in the sky, creatures that consider them a delicious meal.

So why do these cotton bollworms behave this way?

Instead of crawling down to pupate, this cotton bollworm climbs to the top of the tree and writhes.

Do not think poorly of them; these worms were not just playing “high” last night. According to a new study published in the journal Molecular Ecology, scientists have finally uncovered the mystery.

And it is truly horrifying from the perspective of the cotton bollworm: They have been infected by a zombifying virus. This virus strain has taken control of their brain and caused the cotton bollworm to behave in such a life-threatening manner.

Zombifying Virus

It sounds like something out of a horror movie, but this occurs quite frequently in the insect world.

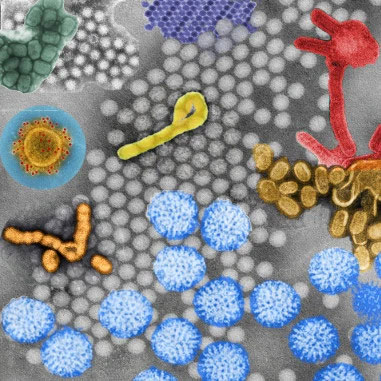

Researchers from the China Agricultural University tested these worms and found that they were infected with a strain of virus known as nucleopolyhedrovirus (HearNPV).

HearNPV Virus.

Once infected, the HearNPV virus quickly takes control of the cotton bollworm’s brain, driving them to climb to the top of the tree. Scientists believe this behavior has a history of millions of years in the evolutionary process.

The HearNPV virus does this so that when the infected worms die high up, they can spread the virus through the wind to infect other hosts. Alternatively, when birds eat them, the HearNPV virus can also transfer from the cotton bollworm to the birds.

At this point, the worms serve as buses transporting the virus to the airport, preparing for takeoff.

How Does the Virus Hack the Cotton Bollworm’s Brain?

Although the HearNPV virus has a long history of hacking the cotton bollworm’s brain for millions of years, the mechanism behind this had only recently been clarified.

“While many researchers have been interested in how parasites and pathogens manipulate the behavior of their hosts, there has been very little in-depth research to accurately determine their characteristics“, said researchers at China Agricultural University.

“Here, we illustrate how HearNPV induces phototropic enhancement in H. armigera larvae by hijacking the host’s visual perception and triggering climbing behavior, causing infected larvae to die at high altitudes.”

A cotton bollworm dead at the treetop.

It turns out that light, rather than altitude or changes in gravity, is what the HearNPV virus uses to control the cotton bollworm’s brain. Chinese researchers conducted several experiments to confirm this.

In the first experiment, they set up a system of nets with LED lights and glass tubes, then introduced infected cotton bollworms into it. The higher the LED lights were placed, the higher the infected worms climbed. Conversely, when the LED lights were placed low, the HearNPV-infected worms crawled down.

The second experiment involved cotton bollworms that had been blinded. The results showed that when the hosts could not perceive light, the HearNPV virus could no longer control the cotton bollworms.

The Chinese scientists named this process phototaxis, or the way organisms orient themselves towards sunlight.

“Since sunlight shines on plants from above, phototaxis is a reliable mechanism [that the virus can hijack its host], ensuring that infected larvae will climb up and die at extreme heights“, the research states.

Cotton bollworm attracted to light after being infected with HearNPV virus.

Not stopping there, the Chinese researchers delved deeper by comparing the genetic differences between infected and uninfected cotton bollworms. They found 6 genes related to light response expressed differently in individuals infected with the HearNPV virus. Ultimately, 3 genes related to phototaxis were discovered.

These three genes are HaBL (a gene that detects short-wavelength light), HaLW (detects long-wavelength light), and TRPL (a gene that converts light into electrical signals). When these genes were knocked out in infected cotton bollworms, they were less likely to be attracted to localized light sources and no longer climbed to the top of the light source.

In summary, the story of the zombified cotton bollworms shows us a peculiar host manipulation mechanism by parasitic species. This is a sophisticated survival strategy that viruses have accumulated over millions of years of evolution.

And if viruses that infect moths can do this, who knows, there may be a strain of virus that infects humans capable of doing the same, which scientists may one day discover.