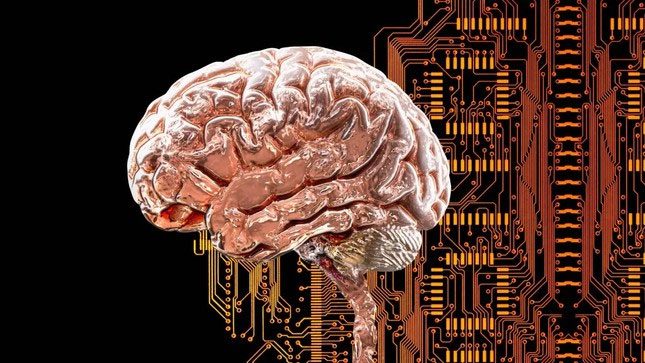

Researchers have discovered that six mental disorders appear to be linked to the same basic neural circuitry in the brain. This is a mysterious network of brain connections associated with several mental disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

“Half of the individuals we treat meet the criteria for multiple disorders,” said Dr. Joseph Taylor, clinical director at the Brain Therapy Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and the lead author of a study describing this finding.

All atrophied regions are connected to a common brain network.

The study identified six disorders—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety—that share this underlying circuitry. Taylor, who is also a collaborating psychiatrist at Brigham and Women’s and an instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, stated: “We suspect that other mental disorders may also be linked to the same network.”

The newly discovered circuitry is not one that scientists have previously identified or named. Taylor noted that previously, some “nodes” in the circuitry were associated with mental disorders, while others were not and were instead linked to key aspects of cognitive function, such as selective attention and sensory processing. Clarifying how this circuitry operates could shed light on how deficits in these functions may lead to various mental illnesses and potentially cause them to occur together.

To map out this complex network, researchers first gathered data from over 190 studies on gray matter differences between individuals with mental disorders and those without.

Gray matter, named for its color, consists of the cell bodies of brain cells or neurons, and the non-insulated wiring extending from those cells. (In contrast, white matter is covered by a layer of insulating fat that coats its nerve fibers). Gray matter is found on the wrinkled outer surface of the brain, the cortex, as well as in several structures beneath the cortex.

The research team precisely identified the brain regions where gray matter has atrophied or shrunk in the context of mental disorders. The team found that two structures in the cortex—the anterior cingulate and insular lobes—frequently appeared in these analyses; however, overall, the pattern of atrophy was inconsistent across the six disorders studied.

Notably, these disorders still share a commonality: a tangled network of wiring runs between all the atrophied pockets in the brain. The research team discovered this by mapping all the regions of atrophied gray matter onto the brain’s wiring system, known as the “connectome”. Another research group had previously constructed this connectome using brain scans of 1,000 individuals without mental disorders.

All atrophied regions are connected to a common brain network.

The question arises: do all six disorders relate to similar functional changes in the circuitry compared to those without mental disorders?

The current connectome offers some clues regarding how the different nodes in the circuitry relate to one another.

Taylor suggested that once scientists gain a better understanding of the circuitry’s role in various disorders, doctors may be able to treat mental symptoms by modulating activity in one part of the network. For example, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)—a non-invasive procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate neurons in the brain and has been approved as a treatment for depression, OCD, and smoking cessation—could be utilized for this purpose.

While the application of TMS for multiple disorders remains theoretical, both Taylor and Barch noted that such treatments could become feasible in the future.