Traces of a mysterious civilization have emerged in the Al-Subiyah desert of Western Asia, taking the form of a peculiar clay head.

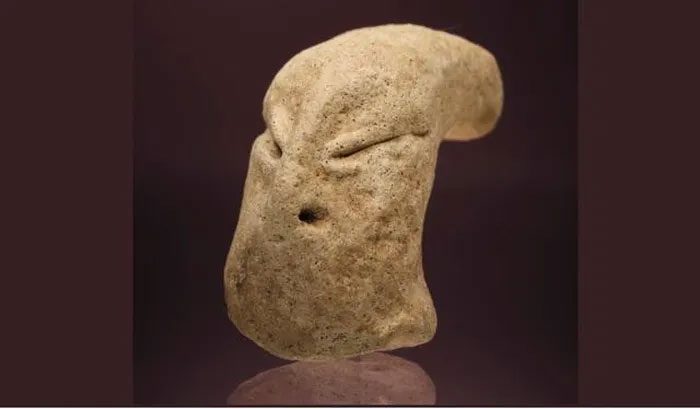

Scientists have dubbed the clay head they discovered as “the snake man,” representing a mysterious prehistoric civilization that thrived in this region from 5500 to 4900 BC.

The “snake man” was found at the Bahra 1 site in the Al-Subiyah desert, located in northern Kuwait, and was analyzed by a research team led by Polish independent archaeologist Piotr Bieliński.

The “snake man” statue from the mysterious Ubaid civilization – (Photo: Adam Oleksiak/CAŚ UW).

The nickname “snake man” was assigned due to the statue’s face, which closely resembles the snake figure in Ubaid culture, characterized by a long skull, flat nose, lack of mouth, and narrow, squinting eyes.

The Ubaid people are considered the first intelligent inhabitants to appear in the Mesopotamian region, yet data about them remains scarce.

Preliminary examination results suggest that the recently unearthed artifact likely belongs to this ancient civilization, providing crucial evidence about the spread of Ubaid customs and beliefs across Western Asia.

The presence of this peculiar face at various Ubaid sites raises intriguing questions about its purpose, symbolic significance, or ritual value to the Ubaid people.

In addition to the snake-faced figures, Ubaid artisans frequently created unusually slender female figures, some with bird or lizard heads.

Long before the Sumerians established one of the earliest and most illustrious civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Ubaid people laid the groundwork with a society characterized by many intriguing features.

The evidence they left behind includes traces of trade networks, irrigation systems, and even astonishing temples scattered across the lands that are now Iraq and Kuwait, along with a unique pottery style that distinguishes them from other cultures.

Their pottery was often made from dry plant materials mixed with clay.

Ubaid pottery – (Photo: Adam Oleksiak/CAŚ UW).

Thus, the discovery of examples of Ubaid pottery and artifacts not only allows researchers to connect this site with a larger narrative about the Ubaid cultural network but also helps to reconstruct the region’s ecosystem over 7,000 years ago.

Botanical archaeologist Roman Hovsepyan from the NAS RA Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (France), a member of the research team, noted that the plants found in the clay used for Ubaid pottery included not only wild plants but also remnants of cultivated plants.

These included barley, wheat, and various other grains, symbolizing an astonishingly developed agricultural system dating back 7,500 years.