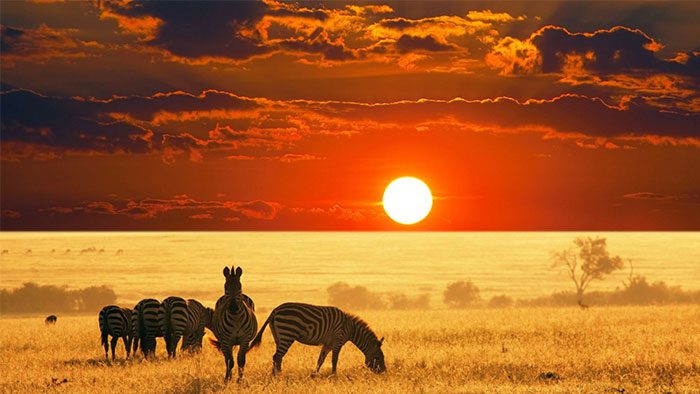

Grasslands are relatively open environments dominated by grasses, and as such, they lack the many hiding spots found in tropical rainforests. However, they serve as habitats for numerous animal species, including both predators and prey.

When an Impala antelope stops at a waterhole to drink, it remains vigilant for nearby predators. Therefore, upon hearing a lion’s roar, they seem to immediately bolt to safety. In contrast, if they hear the sound of a cheetah, they will continue drinking, feeling undisturbed by the potential threat nearby.

Hoofed animals are most likely to flee from lions.

Many hoofed animals in South Africa exhibit varying fear responses depending on the nearby predator species. This is a significant finding from a recent study published in the journal Behavioral Ecology, where researchers indicated that hoofed animals are most likely to flee from lions, followed by African wild dogs, and then cheetahs.

According to Liana Zanette, co-author of the study and a wildlife ecologist at Western University in Canada, “this hierarchy of fear” is crucial because fear influences all aspects of predator behavior and can have cascading effects throughout the ecosystem.

“You can see that if they have different fear responses, it will affect their foraging behavior,” Zanette said. She added that, “this can then affect prey population numbers and impact their food sources deeper in the food chain.”

Prey may fear predators with the highest likelihood of killing them.

To test the fear responses of hoofed animals to different predators, the scientists first collected audio recordings of lions, cheetahs, and African wild dogs, as well as bird calls to use as a control for fear. They employed short-range sounds like growls to simulate a predator nearby.

They then played these sounds to wildlife using a speaker connected to a camera trap. When the camera detected an animal moving nearby, it would start recording video and then activate the speaker to play the predator sounds.

The researchers set up the camera and speaker system at 14 different locations and operated them day and night for several weeks in July 2017.

The scientists proposed three hypotheses regarding how hoofed animals would react to each predator.

- First, they might perceive all predators as equally frightening, in which case they would frequently flee from all three predators.

- Second, they might show the most fear towards the predators that frequently kill their kind.

- Third, prey may fear the predators with the highest likelihood of killing them if they decide to attack, which would be the lions.

After collecting hundreds of videos of startled animals during their experiments, the researchers reviewed them and found the results aligned with the third hypothesis. “It truly is a hierarchy of fear because the animals fear lions the most,” Zanette said, “followed by wild dogs, then cheetahs.”

Upon hearing a lion’s roar, the Impala antelope immediately flees.

The animals most frequently captured on camera were the Impala antelope, clearly indicating this fear hierarchy. However, Zanette explained that lions do not typically pursue Impalas. Instead, Impalas are more likely to be attacked and eaten by wild dogs or cheetahs.

Zanette stated: “Although Impalas are the primary prey for lions, they still fear lions the most; we think this is due to the high success rate of predation. Once lions decide to chase them, the mortality rate for Impalas is quite high,” Zanette said.

Predators with different hunting behaviors can also trigger different responses in their prey.

Elizabeth le Roux, a large mammal ecologist at Aarhus University who was not involved in the study, noted that predators with different hunting behaviors can also elicit different responses in their prey. She stated that the best way to avoid being eaten by lions is to run, while with pack hunters like African wild dogs, stopping and assessing the surroundings might be a wiser move.

Additionally, Kaitlyn Gaynor, a wildlife ecologist at the University of British Columbia who was not involved in the study, mentioned that understanding this complexity in predator behavior can be crucial for their conservation. She explained that humans have altered many ecosystems by removing certain predator species while introducing others, which then act as new predators.

African Wild Dog.

These predators can have significant impacts on the landscape. For example, a 2014 study showed that the predation risk from leopards and wild dogs shapes the habitat preferences of antelopes, thereby altering the distribution of plant species in the Kenyan savanna.

Thus, the loss or re-emergence of a predator can trigger cascading effects throughout the entire ecosystem. Zanette stated: “The reason predators can have such impacts on prey populations and ecosystems is that they not only kill them but also instill fear, and fear has enormous effects that we have not fully assessed.”