The oldest solar observatory in the Americas has been discovered on the coast of Peru. This site is considered a location for rituals that provides evidence of the “Sun God religions” that operated in South America over 2,300 years ago.

Previously, archaeologists uncovered 4,000-year-old pottery fragments in Peru depicting an “authority-holding deity” with rays emanating from its head, possibly resembling the Sun (the oldest religious symbol in the Americas).

Historical records also describe “Sun pillars”, indicating that the Inca civilization of South America observed the Sun—potentially to mark planting times—around 1,500 AD, although these pillars have since been destroyed.

The Chankillo Observatory, built by an ancient civilization. The ruins atop a hill are located about 400 km north of Lima. The stone towers at Chankillo have been known for a long time, but their astronomical significance was not widely recognized and had long been forgotten by scientists. Then, in 2007, a study published in the journal Science proposed the sequence of the towers, which were erected between 200 and 300 BC to “mark the summer and winter solstices,” and Chankillo “is part of the solar observatory.”

The Incas also held public ceremonies to observe the sunrise or sunset at marked positions on the horizon, and ancient Inca leaders claimed their right to rule through “kinship” with the Sun.

Peruvian archaeologist Ivan Ghezzi and co-author Clive Ruggles from the University of Leicester, UK, stated that earlier civilizations in Peru may have also observed the Sun, possibly as early as the fourth century BC.

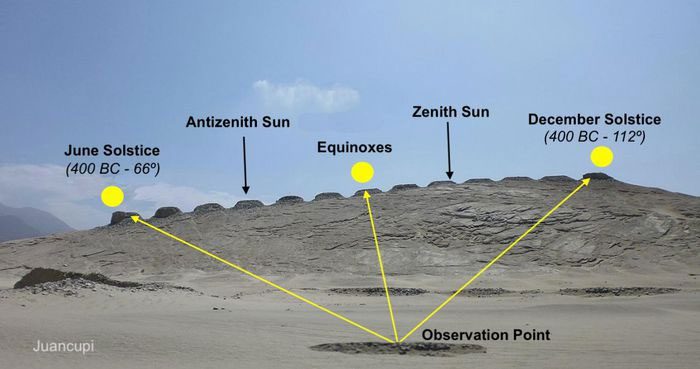

The towers were precisely constructed to mark various solar positions. Their purpose was to time the months, solstices, and equinoxes—marking planting and harvesting seasons as well as religious holidays. Its operational structure resembles a gigantic clock, marking the passage of time over a year.

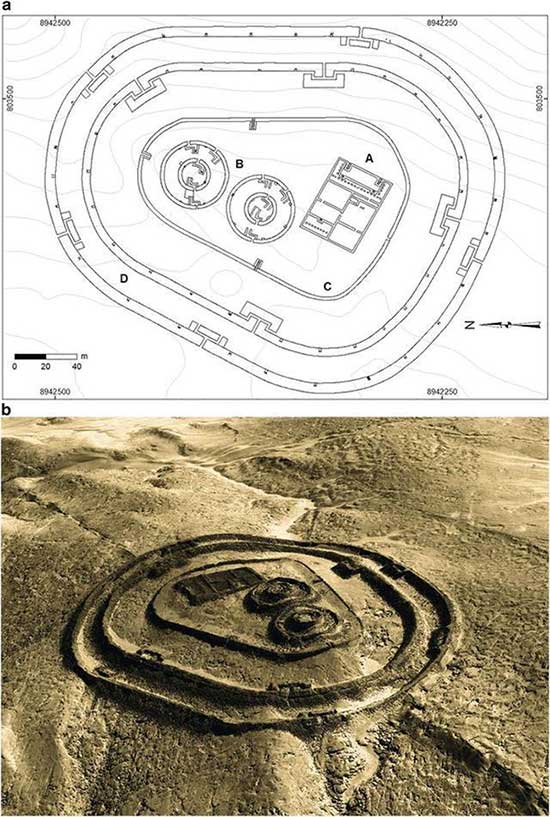

They concluded their findings based on the remains at a coastal site in Peru known as Chankillo. Once thought to be a ceremonial center or fortified temple, researchers now believe the central complex of the ruins may have actually served as a solar observatory.

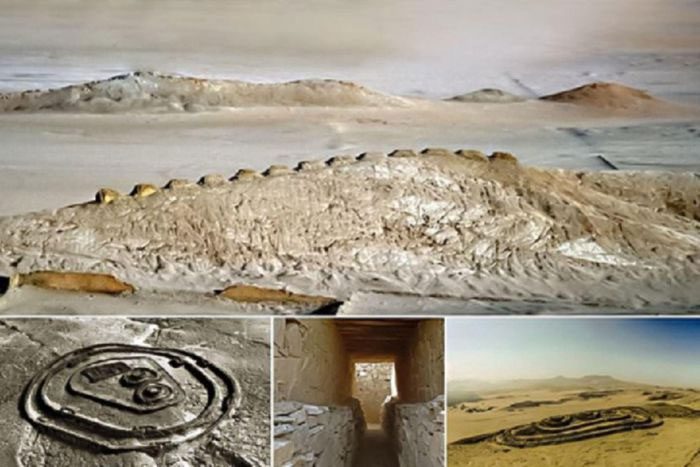

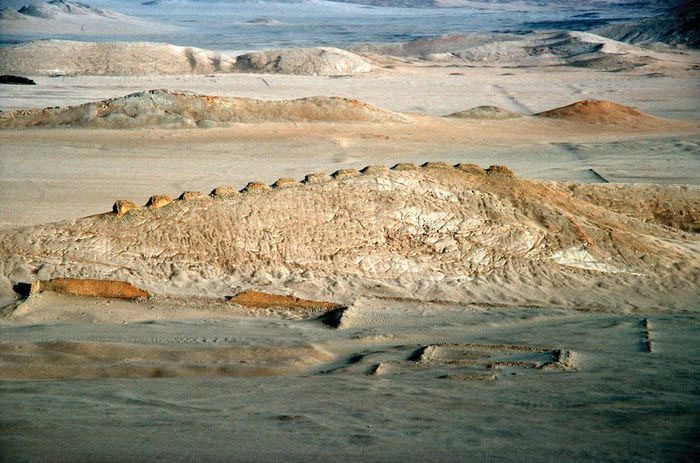

At Chankillo, 13 rectangular towers are evenly spaced along a 300-meter slope, resembling a spine, creating an artificial horizon. According to measurement data, the 13 stone towers at Chankillo are spaced between 4.7m and 5.1m apart. At the time of construction, the tops of the towers were completely flat. Each tower varies in shape and size, with widths ranging from 70 to 130m and heights reaching up to 6m. They are aligned along the positions of the Sun’s rise and set, gradually shifting north and south along the horizon throughout the year.

On either side of the slope are the remains of observatories (with two observatories located to the east and west)—scientists believe these were used to observe the Sun rising or setting between the towers. On the summer solstice, the Sun rises between Tower 1 and a nearby mountain, while on the winter solstice, it rises around Tower 13. This site may have been a venue for public ceremonies and festivals related to the seasons and the Sun. Excavations have uncovered pottery, shells, and other artifacts near an opening at the western observation point.

The Sun only appears for one or two days in each gap between the towers and takes six months to traverse from one end to the other of the structure. Thus, different towers may have been used to divide the year into regular intervals.

“Chankillo is a masterpiece of ancient Peru. A masterpiece of architecture, a masterpiece of technology and astronomy. It is the cradle of astronomy in the Americas,” Ghezzi said. It may also have served as a place of worship for the Sun. Locations to the east and west of the towers contain remnants of objects used for sacrificial rituals. The observatory and its ceremonial components are protected by fortress walls made of stone, mud, and tree trunks. Ghezzi noted that the complex spans approximately 5,000 hectares, but only about one percent of it has been studied.

“This is the only observatory in the ancient world that we know of that could be used to calculate a complete solar calendar over a year. A total of 13 towers are positioned to align with the Sun’s movement through the seasons from two different observation points. There is no equivalent to this anywhere in the Americas or the world,” Ghezzi stated. Chankillo is among the sites that have been “invaded”; not by thieves, but by nearby farmers who have long sought to expand their land and have exploited the lack of control to plant crops within the site’s boundaries.

Chankillo is the third site in Peru to be designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site this century. Previously, this honor was awarded to Qhapaq Ñan—a vast Inca road system—in 2014 and to Caral—the oldest city in the Americas—in 2009.