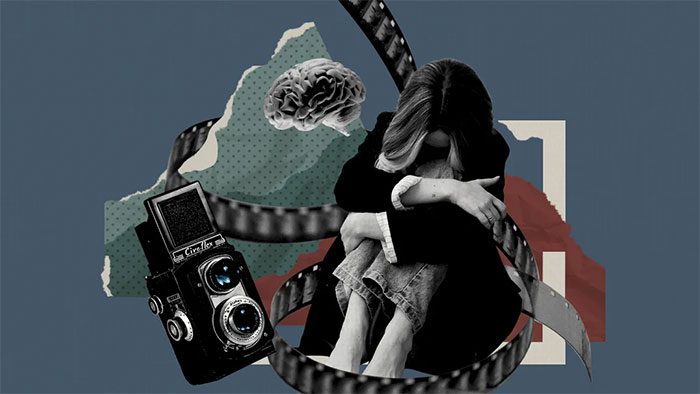

(khoahoc.tv) – When a person experiences a significant loss or a tragic event, why do all the details seem to be etched into memory, while a series of positive experiences fade away?

According to a recent study published in the neuroscience journal by researcher Sabrina Segal from Arizona State University, this phenomenon is much more complex than scientists initially speculated.

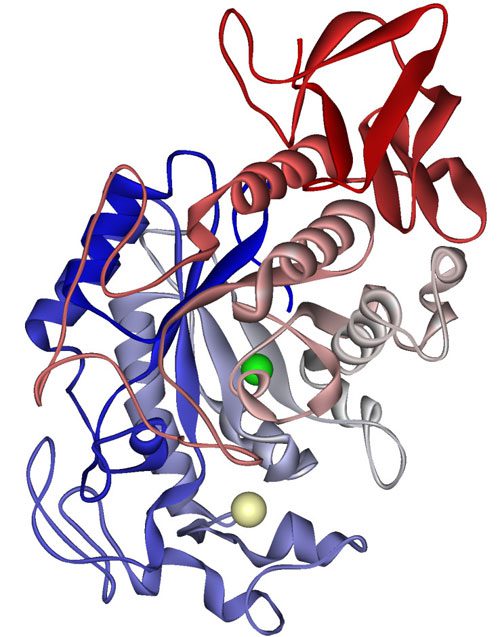

When the brain retains memories about objects, it creates a distinct pattern of activity for each of those objects. Stress alters the traces of memory and separates them from objects belonging to other experiences.

If both happy and stressful memories are emotional, what is the difference in how the brain retains them? The answer lies in the hormones released when the body encounters stress.

When we undergo a painful event, the body releases two main stress hormones: norepinephrine and cortisol. Norepinephrine increases heart rate and controls the fight or flight response, often rising when we feel threatened or experience strong emotional reactions. Chemically, this is similar to the hormone epinephrine – also known as adrenaline.

In the brain, norepinephrine functions as a powerful neurotransmitter or chemical signal that can enhance memory.

Research on cortisol has shown that this hormone can have a strong impact on memory enhancement. However, studies in humans so far have been inconclusive – with cortisol sometimes enhancing memory while at other times having no effect.

An important factor in whether cortisol influences memory enhancement may depend on the activation of the norepinephrine hormone during the learning process, a finding previously observed in studies on mice.

In her study, Segal – an assistant research professor at the Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research Institute (IISBR) at Arizona State University, along with her colleagues at the University of California, Irvine – demonstrated that the memory enhancement functions in humans are similar.

Conducted in Larry Cahill’s laboratory at the University of Irvine, Segal’s study included 39 women who were shown 144 images from a collection known as the International Affective Picture Set. This set of images is a standard collection used by researchers to elicit a range of responses, from neutral to strong emotional reactions, after viewing.

Segal and her colleagues administered a dose of hydrocortisone – to simulate stress – or a placebo to each study participant just before they viewed the image set. Each woman then self-assessed her emotions after viewing the images, and the researchers collected saliva samples before and after viewing the pictures. A week later, a surprise recall test was conducted.

What Segal’s research team found was “that negative experiences are more easily remembered when an event is traumatic enough to release cortisol, and only when norepinephrine is released during or immediately after this event.”

“This study provides important insights into how painful memories can be enhanced in women,” Segal added. “Because it suggests that if we can intervene to reduce norepinephrine levels immediately after a traumatic event, we may be able to prevent this memory enhancement mechanism from occurring, regardless of how much cortisol is released when an individual experiences a painful event.”

Further studies are needed to explore how the relationship between these two stress hormones may depend on gender, particularly since women are at a higher risk of developing stress-related disorders that affect memory, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Another reason stems from the evolutionary history of humankind.

Age also plays an important role in what people choose to remember and forget.

Elizabeth Kensinger, a professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Boston University, explains: “Human instinct is set for survival, protecting them from life-threatening situations. Therefore, it makes sense that the brain’s attention would focus on things that have the potential to threaten.”

Metaphorically, Laura Carstensen, a psychology professor at Stanford University, told The Washington Post in 2018: “For survival, paying attention to the lion lurking in the bushes is more important than noticing the beautiful flower blooming across the street.”

Additionally, age also plays a significant role in what people choose to remember and what to forget.

Professor Carstensen believes that the brain selectively processes and retains images and information that appear in stressful situations to address similar issues in the future.

“When younger, individuals often think they have a long future ahead and need to gather as much information and knowledge to ‘manage’ their lives. As they age, they gradually shift to living in the present and thus focus on memories that are more positive and uplifting,” she explains.