The bubble curtain, a technology that helps keep the fjords in Norway from freezing in winter, could potentially prevent strong storms in the Gulf of Mexico in the future.

Imagine the summer weather in Louisiana, USA, very hot and humid around the mid-2020s. Weather experts are monitoring a low-pressure system forming in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Puerto Rico. Previously, the weather had only been characterized by light winds and rain, but the sea temperature is warmer than 27 degrees Celsius near Cuba, right along the projected path of the storm. Warm eddies are appearing throughout the Gulf of Mexico. Computer models warn that the storm could develop into a Category 4 hurricane when it makes landfall in New Orleans.

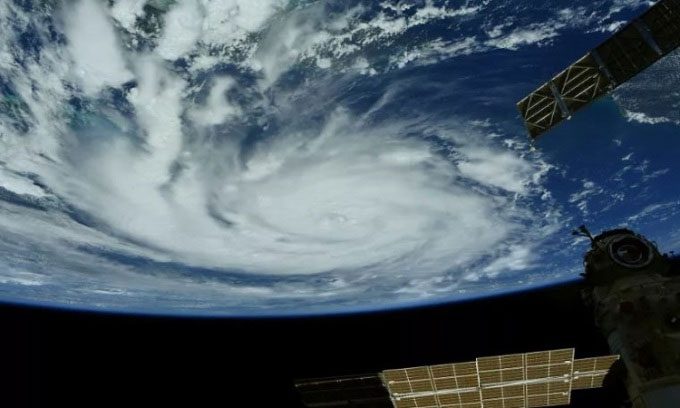

Astronaut Thomas Pesquet captures Hurricane Ida from the ISS. (Photo: ESA)

A liquid cargo train equipped with powerful compressors and a complex multi-pipe system heads towards Cuba to test an invention that Norwegians have used for decades to prevent the fjords from freezing in winter. Some residents are skeptical about the effectiveness of the technology and believe that authorities should invest in reinforcing drainage systems. However, computer simulations and small-scale tests yield positive results.

This scenario is hypothetical, presented by OceanTherm and their CEO, computer engineer and former Norwegian Navy submariner Olav Hollingsaeter. The technology under consideration is the bubble curtain. The purpose of this technology is to mix cold water from a depth of 150 meters with warmer surface water. The water temperature only drops a few degrees Celsius but is sufficient to deprive tropical storms of their energy supply and prevent them from intensifying.

A recent study by the independent research institute SINTEF in Norway shows that a 30-kilometer long, 100-meter deep bubble curtain would reduce the surface sea temperature from 28.9 degrees Celsius to 26.1 degrees Celsius. The study is based on computer modeling, using ocean data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the World Ocean Atlas, combined with climate and atmospheric datasets from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

The bubble curtain technology simply involves releasing air from an underground pipe. As the bubbles rise, they carry cold water from the deep and mix it with the warmer water at the surface. Natural currents then spread the cooler water throughout the wider ocean area. The research indicates that after 48 hours of bubble generation, the effects can be measured over an area of 30 by 90 kilometers. “We were very surprised that the evidence from the computer simulations confirmed OceanTherm’s hypothesis,” said Paal Skjetne, a research scientist at SINTEF.

This result is a significant encouragement for Hollingsaeter, who has been exploring the idea of using bubble curtains to prevent storms since 2005. He stated that the next step is to conduct a small-scale test with a 1.5-kilometer wide bubble curtain in the Gulf of Mexico to demonstrate the effectiveness observed in the models.

Setting the surface temperature at 28.9 degrees Celsius in the experiment is not coincidental. This is the temperature at which storms develop. Most of the devastating storms over the past decade, including Katrina in 2005, Harvey in 2017, and Ida in 2021, intensified as they passed over hotspots and warm eddies in the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico.

“Hurricane Harvey was just a tropical depression before it passed over very warm waters, and then it quickly developed into a Category 4 hurricane,” Hollingsaeter noted. “Hurricane Katrina was similar. Therefore, we believe that if we target hotspots and warm eddies before a storm passes through, we can prevent them from intensifying into a devastating hurricane.”

Hollingsaeter estimates that operating a patrol for warm eddies would cost about $350 million each hurricane season. The damage from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was approximately $180 billion, and Hurricane Ida in August was $65 billion, according to NOAA. “We have no other way to prevent a Category 4 hurricane. We need to do it while the storm is still small and relatively weak.”