Biodiversity is uneven, manifested in many equally evolved sister branches, some having many species while others have very few.

It is often believed that during the evolutionary process of biodiversity, many large evolutionary branches have emerged through rapid evolution and they have higher biodiversity; while smaller branches that undergo slower evolution tend to have lower biodiversity.

High evolutionary rates are hard to sustain long-term

However, in the 1940s, the famous paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson presented a contrary viewpoint in his classic book The Rhythm and Pattern of Evolution.

Simpson believed that rapid evolution can lead to instability and extinction, while slow evolution can lead to higher biodiversity. Because high evolutionary rates are difficult to sustain long-term, they can render evolutionary branches unstable to the point of extinction or lead them to transition to slower evolutionary rates. By studying basic evolutionary mechanisms within the framework of Darwin’s theory of evolution, he found that many rapidly evolving species actually belong to unstable groups, and these groups may adapt to rapidly changing environments.

This is a challenging perspective. Now, a new study published in the journal Paleontology has found evidence to support Simpson’s claims by investigating lizards and some of their close relatives. Simply put, their research results show that the faster they evolve, the quicker they face extinction.

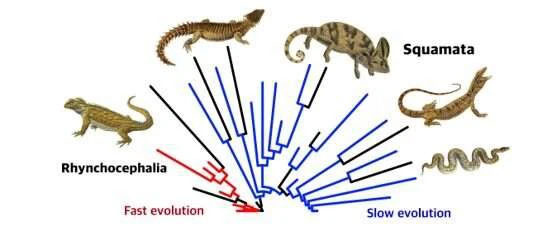

In this new study, researchers analyzed a group of animals known as Lepidoptera, which includes lizards, snakes, and some of their close relatives. The subclass Lepidodendron originated in the early Mesozoic era about 250 million years ago and can be divided into two main types: Squamata (scaled reptiles) and Rhynchocephalia (tuatara). Among them, Squamata has developed into more than 10,000 species of animals like modern lizards and snakes; and Rhynchocephalia now consists of only one species – the tuatara (also known as the New Zealand lizard).

The Lepidoptera animal group.

Prior to this study, researchers expected to find traces of slow evolution in tuataras and signs of rapid evolution in scaled reptiles. However, what they observed was completely contrary to their expectations. They discovered that during the first two-thirds of the evolutionary history of the Squamata order, there was a slow evolutionary rate; and its sister evolutionary branch, Rhynchocephalia, although currently consisting of only one species, showed rapid evolution in the past.

The researchers investigated the rate of body shape change in these early reptiles and found that while some scaled reptiles (especially those with specialized lifestyles) evolved very quickly during the Mesozoic, the rate of evolution in tuataras was significantly faster than the average evolutionary rate of scaled reptiles – about twice the baseline evolutionary rate. This discovery exceeded the researchers’ expectations.

By the end of the Mesozoic, all modern lizard and snake species had emerged and began to diversify. They coexisted with dinosaurs but may not have interacted with them ecologically. Most of these early lizards were small, feeding on insects, worms, and plants.

By the end of the Mesozoic, all modern lizard and snake species had emerged and began to diversify.

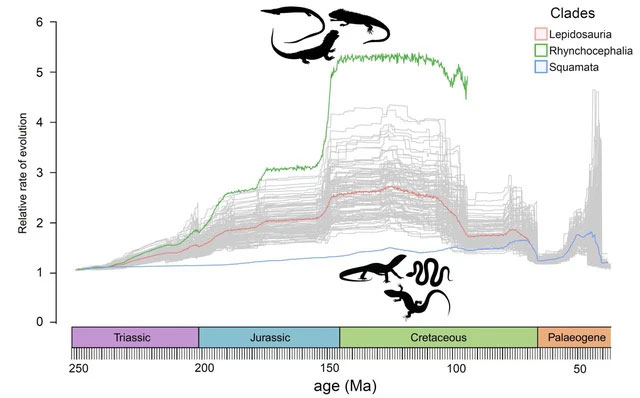

For about 200 million years, the evolutionary rate of lizards and snakes (scaled) was much lower than that of tuataras, and this only reversed in the last 50 million years. The red line represents the average evolutionary rate of all Lepidoptera subclasses throughout geological periods.

About 66 million years ago, after the extinction of the dinosaurs, tuataras and scaled reptiles were heavily impacted. However, the number of scaled species later recovered; and for most of the Mesozoic era, tuataras began to evolve at an extremely fast rate, before their evolutionary rate slowed down again at the end of the Mesozoic.

We have all heard the story of The Tortoise and the Hare in Aesop’s Fables, where the fast-running hare loses to the slow but steady tortoise. The message of this story is that only persistent effort can lead to victory in the race. In reality, since Darwin’s time, biologists have debated whether the evolutionary process resembles that of the hare or the tortoise in The Tortoise and the Hare. Are many species-rich groups the result of rapid evolution over a short time or the result of slow evolution over a long time?

Judging from the results of the latest research, the slow and steady survival strategy has allowed scaled reptiles to win the race; while the rapidly evolving and thriving tuataras of the past have been outpaced, leaving only one surviving species. For rapidly evolving groups, they may sometimes stabilize and survive well, but in many cases, their extinction rate will be very fast, as quick as the emergence of new species, ending like a sleeping hare in the race.

Additionally, according to Simpson’s predictions, slow-evolving species can also face gradual extinction, and may ultimately be more successful than rapidly evolving species over a longer period, much like the tortoise that moves slowly but steadily in the fable. Going forward, researchers hope to explore more groups of organisms, thereby demonstrating that rapid evolutionary processes may lead to high diversification in the short term, but ultimately result in lower biodiversity in the long term.