In the era of the intersection between science and spiritualism, one of the most famous confrontations between magician Harry Houdini and medium Mina Crandon captured public attention. This event not only revealed the conflict between reality and supernatural belief but also reflected a turbulent period when scientific discoveries coincided with a desire to reach the afterlife.

On a July day in 1924, O.D. Munn, editor of Scientific American, along with six other scientists gathered in a stuffy room in Boston. They were not there to conduct a typical scientific experiment but to examine the supernatural claims of Mina Crandon – also known as “Margery” – a woman with the ability to communicate with the dead, who was stirring public excitement in America at the time. This event, featuring Harry Houdini, a world-renowned magician and skeptic of spiritualism, became one of the most famous confrontations between the worlds of science and superstition.

Spiritualism spread across the Western world throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

This meeting was the result of a wave of interest in spiritualism, a cultural movement that flourished across the Western world during the 19th and early 20th centuries. This movement not only captivated the general public but also attracted the attention of leading scientists such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Believing that science could prove the existence of the afterlife, Doyle even invited Munn to witness Crandon’s abilities in hopes of helping her win a $5,000 prize for anyone who could demonstrate the existence of supernatural phenomena.

The Age of Science and Belief in the Supernatural

The 19th century is often referred to as the “age of science,” when natural laws increasingly shaped humanity’s worldview. It was also a period of impressive scientific and medical discoveries, such as James Prescott Joule’s contributions to the Law of Conservation of Energy and the first use of anesthesia in surgery. However, despite the remarkable advancements in science, spiritualism persisted and thrived, attracting both the public and intellectual circles.

The spiritualist movement began in the 1840s when the Fox sisters in New York claimed to communicate with the dead through knocks and strange sounds. Although they later admitted it was a hoax, at the time, séances attracted a large following. Spiritualism gradually evolved into a cultural branch, spreading throughout Europe, even including the scientific community and famous artists. Such séances became a “laboratory” for exploring spiritual phenomena.

Richard Noakes, a professor at the University of Exeter, remarked that the 19th century was a time when the boundaries between science and spiritualism were not yet clear. Many scientists, in their attempts to understand the afterlife, employed research methods that today might be considered pseudoscientific. Proponents of spiritualism believed that the phenomena of séances were not “supernatural” but simply aspects of nature that science had yet to explore.

The advent of the telegraph set the stage for spiritualism.

The Telegraph and the Desire to Connect Two Worlds

Advancements in communication, particularly the invention of the telegraph, laid the groundwork for spiritualism. Since the telegraph was invented and developed, information could be transmitted over long distances almost instantly, something unprecedented before. For contemporaries, if information could travel at the speed of light across great distances, why couldn’t the living connect with the afterlife in a similar manner?

Accordingly, many spiritualists viewed these inventions as evidence that there might be invisible means of communication that we have yet to fully understand. They believed that if technology could connect continents, it could also bridge two worlds – a “telegraph” of sorts to communicate with the souls of the deceased. Séances became venues to test this theory, where mediums often requested “guests” from the spirit realm to respond by knocking or producing sounds.

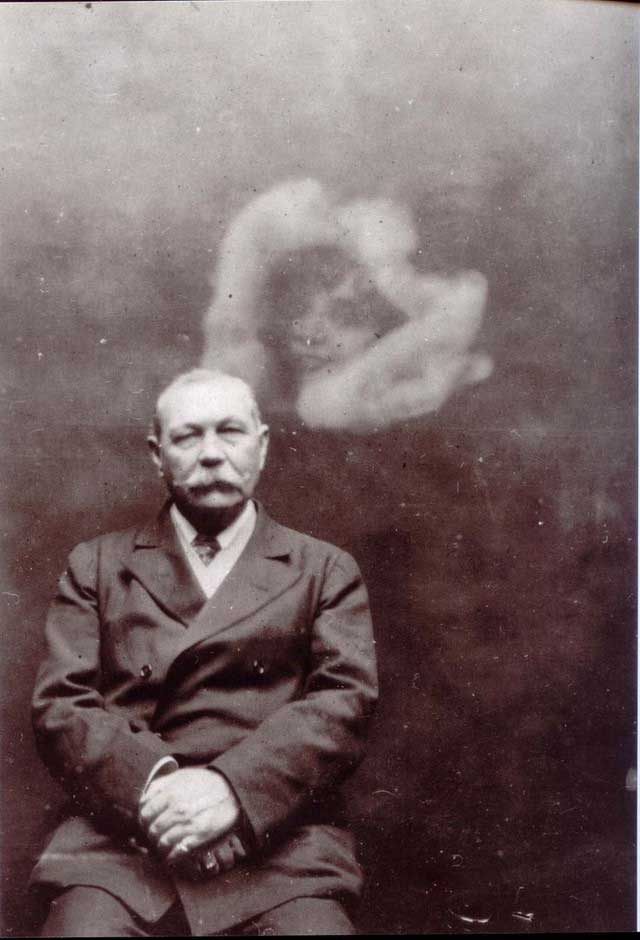

The Influence of Photography and the Quest for Evidence of Souls

As photography technology advanced, it was quickly utilized by spiritualists as a tool to “capture” evidence of souls. It was believed that if photography could document things invisible to the naked eye, it could also capture images of spirits. Many famous “spirit photographs” emerged in the 19th century from this concept, but in reality, photographers used techniques like double exposure and lighting effects to create these apparitions.

William H. Mumler and Frederick Hudson were among the photographers who employed this technique to produce images containing “ghosts.” The appearance of these photographs increased public confidence in photography’s ability to document evidence of the afterlife. However, with technological advancements, the allure of “spirit photographs” gradually diminished as people recognized they could be created through sophisticated means.

The appearance of these photographs increased public confidence in photography’s ability to capture ghosts.

The Decline of the Spiritualist Movement and Modern Science

By the early 20th century, the spiritualist movement began to wane as mediums like Mina Crandon were exposed for fraud. At the Scientific American examination in 1924, Harry Houdini publicly replicated Crandon’s tricks, demonstrating that no supernatural elements were involved. This shattered faith in Crandon and dealt a significant blow to spiritualism, transforming it from a major cultural movement to a subject on the fringe of science.

Although enthusiasm for spiritualism faded, it had, for a time, sparked a wave of interest that connected the most curious minds of the era. Those seeking truth about the afterlife believed that science, rather than mysticism or superstition, would be the path to uncovering reality. Even today, science and spiritualism no longer coexist, the story of scientists pursuing spiritualism is an intriguing part of scientific history. Thus, the ghosts of the past should not be forgotten but understood, allowing us to view the past and the world around us with openness and tolerance.