The “Ten-Sided Lingbi” Painting by Ming Dynasty Artist Guo Bian Sells for $78.2 Million.

Ten-Sided Lingbi is the most expensive ancient artwork in China, fetching a staggering 512 million yuan ($78.2 million) at a special auction commemorating the 15th anniversary of Poly Beijing in October 2020.

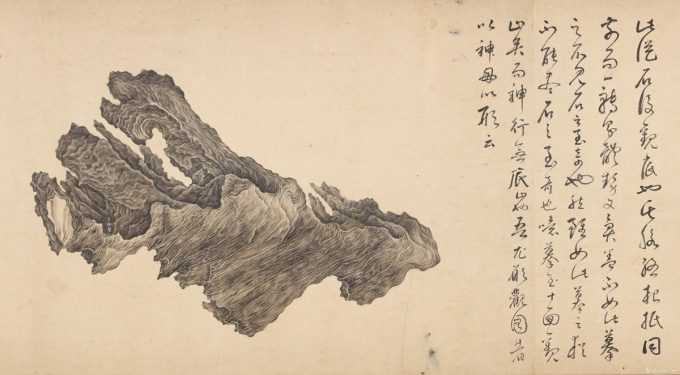

The painting of the rock “Ten-Sided Lingbi”. (Video: YouTube Grand View Garden)

The artwork originated from the love of stones by Mei Wanchong – a scholar and calligrapher of the late Ming Dynasty, known as the recluse Shiyan An. In 1608, during a visit to Lingbi County in Anhui Province, Mei Wanchong purchased a stone resembling a majestic mountain, which brought him immense joy and sleepless nights. He declared it the best stone in his collection, naming it Fei Fei Stone, implying “a stone but not just any stone”. The text Mei Shi Qi Shi Ji describes it as: “Strange shape, elongated like a mountain, with branches alternating. Below is a small, thin square base. Dark color with dense patterns, thin like water cascading.”

He then invited his close friend Guo Bian – a court painter – to admire and paint it. The work spans 11.5 meters, depicting ten sides of the stone in order: front, back, left, right, four diagonal corners, and two perspectives of the base, all to scale. According to Sanlian Life Week, the decision to paint the stone from ten angles was spontaneous. During the creative process, different facets of the object captivated the artist’s vision, leading him to depict two, then four, then eight, and finally all ten angles. In addition to traditional brush and ink, the artist incorporated geometric principles, rhythms, and the theory of the five elements. “His painting concepts and techniques are hard for later generations to surpass,” the magazine noted.

The artist illustrated the stone with thin and dense lines interwoven like strands of hair. The painting was created continuously over nearly two years, from 1608 to 1610. Experts believe that the artist spent at least a month on average for each side.

The Science and Technology Department of the Palace Museum previously reconstructed a 3D model of the stone based on the ten angles depicted in the painting. The conclusion showed that Guo Bian realistically painted every peak and fold of the stone. “More than 400 years ago, without photographic technology, how did the artist paint the stone at a 1:1 scale? This is very difficult as it is not flat but 3D. One can imagine that Guo Bian painted from many angles yet connected them almost seamlessly. The original shape of the stone was represented very accurately. This is hard to fathom,” they stated.

After the completion of the work, Mei Wanchong traveled thousands of miles inviting renowned literati of the time such as Dong Qichang, Chen Jiexiao, Li Yuzheng, and Ye Xianggao to write commentaries on the painting, marking a significant cultural event.

According to historical records, one day in early 1615, the calligrapher and painter Dong Qichang, then 60 years old and residing in Jiangnan, received the artwork sent by Mei Wanchong from Beijing. As he slowly unwrapped it, what appeared before him was not a traditional landscape or familiar figure painting, but an image of strange and rugged stones, accompanied by ten descriptive passages. He composed a lengthy inscription on the painting, expressing his admiration, including the line: “I see the winding water, the sharpness of metal, the beauty of trees, the depth of the earth, and even fire through the stone. These elements can be called the five elements.”

The final side of the painting. (Photo: Culture and Art Network)

During the reign of Emperor Daoguang of the Qing Dynasty, Ten-Sided Lingbi belonged to General Zha Yeng A of the Manchu ethnicity. He inscribed a note on the painting to describe the collection process. The artwork was later passed to his son-in-law, the governor of Shandong – Ai Shan. For a long time, the whereabouts of the painting remained unknown.

In December 1989 at Sotheby’s in New York, Ten-Sided Lingbi made its auction debut, capturing the public’s attention. Most attendees were Western collectors. The artwork was subsequently purchased by American collector William Bernard Ziff for $1.21 million – a record for the auction of Chinese paintings and calligraphy at the time. He was an art enthusiast, especially fond of the stones in his mother’s jewelry. After Ziff’s death in 2006, the piece was kept by his family and sold in 2020.

According to Sanlian Life Week, the stone was once displayed in one of Mei Wanchong’s three residences in Beijing. After his death in 1628 and the ensuing turmoil of the Ming dynasty, the residence changed owners, and the stone’s fate became unclear from that point onward.

Guo Bian (1550-1643) was a famous landscape painter during the Ming dynasty, under the reign of Emperor Wanli. Many of his works are currently housed in the Palace Museum.