Written by Newton in Latin, the three main principles of motion of objects in the universe have been translated, interpreted, and understood not entirely accurately.

In 1687, when Isaac Newton penned the laws of motion that have since become famous, he likely hoped that three centuries later we would be discussing these laws.

In his Latin manuscript, the scholar Newton outlined three universal principles describing how objects move in the universe. These principles have been translated, recorded, discussed, and debated extensively.

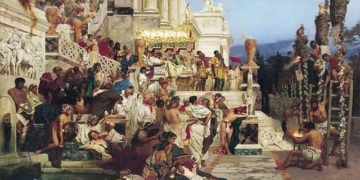

A spinning top is an example Newton used to explain the laws of motion. (Photo: Tetiana Shyshkina/Unsplash).

However, according to a philosopher of language and mathematics, we may have misinterpreted what Newton wrote. Philosopher Daniel Hoek from Virginia Polytechnic Institute discovered a “clumsy mistranslation” in the original English translation of Newton’s book, *Principia*, published in 1729.

According to this translation, countless scholars and teachers have interpreted Newton’s first law of inertia to mean that an object will continue moving in a straight line or remain at rest “unless” acted upon by an external force.

This interpretation has been rigorously applied until you acknowledge that external forces continuously act upon objects, something Newton surely considered when he expressed his ideas.

Upon reviewing archival documents, Hoek found that this popular translation was inaccurate, unnoticed until 1999 when two scholars discovered a misinterpreted Latin word. That word is “quatenus”, meaning “insofar as” rather than “unless.”

For Hoek, this creates a completely different understanding. Instead of describing how an object maintains its momentum without external forces acting on it, he argues that the new interpretation shows Newton intended to say that every change in an object’s motion—every bump, tilt, deviation, and leap—is caused by external forces.

Hoek argues that by restoring the forgotten word “insofar as” to its rightful position, the two scholars have accurately restored the essence of one of the three fundamental laws of physics. However, this crucial adjustment has yet to be made.

Even today, this adjustment faces the weight of the centuries-old replication and dissemination of the old translation. Hoek states that: “Some people believe my reading is too naive, crude, and unusual to be taken seriously, while others think the long-standing translation is so correct that it hardly merits debate.”

Ordinary individuals might agree that the two translations sound similar in meaning, and Hoek also acknowledges that re-translating won’t change physics, but a careful examination of Newton’s writings would lead us to a more accurate understanding of what the scholar thought when he wrote those documents.

Since his student days, Hoek has been puzzled about why so much ink has been spilled dissecting the question of the law of inertia. If we use the common translation that objects move in a straight line until a force compels them to change direction, then the question arises: “Why did Newton write a law about objects not being acted upon by external forces when there are always gravitational and frictional forces in our universe?”

Philosopher George Smith from Tufts University, an expert on Newton’s writings, states that: “The whole purpose of the first law is to infer the existence of forces.”

In fact, Newton provided three specific examples to illustrate the first law of motion, one of which is a spinning top that slows down in a tightening spiral due to air friction.

According to Hoek, by presenting this example, Newton clearly shows how the first law applies to accelerating objects influenced by force, meaning it applies to objects in the real world.

Hoek believes this revised interpretation provides one of Newton’s most revolutionary ideas at the time. That is, planets, stars, and other celestial bodies are governed by the same physical laws as objects on Earth.

“Every change in speed and every tilt in direction, from atoms to spiral galaxies, is governed by Newton’s first law,” he says. And that connects us to the most distant reaches of the vast universe.