Today, all around the world, if people see news images in newspapers, magazines, textbooks filled with specific photographic evidence, if doctors can examine patients through X-ray films, and if people enjoy entertainment thanks to movie theaters, then all these inventions have developed thanks to the dedication of a remarkable genius in the field of photography, George Eastman.

Today, all around the world, if people see news images in newspapers, magazines, textbooks filled with specific photographic evidence, if doctors can examine patients through X-ray films, and if people enjoy entertainment thanks to movie theaters, then all these inventions have developed thanks to the dedication of a remarkable genius in the field of photography, George Eastman.

Thanks to Eastman’s creative genius, the previously complicated and challenging process of taking photographs has become easy, requiring only a simple action of pressing a button on a handheld camera, which operates in a fraction of a second, allowing for highly realistic images.

George Eastman’s invention revolutionized photography, simplifying the task of capturing the current world’s images to pass on to future generations. His invention also contributed to scientific research, from studying tiny entities like microbes and atoms to observing massive celestial bodies such as enormous nebulae. Photography has also found applications in medicine, industry, science, education, art, and even entertainment.

1. Early Years.

George Eastman was born to George Washington Eastman and Maria Kilbourn on July 12, 1854, in Waterville, New York. His father was a nurseryman who sold the family business when George was six years old, moving the family to Rochester to open a commercial school. Two years later, George’s father passed away, leaving behind a wife and three children, including two daughters and a son, all living in poverty. During this challenging time, Mrs. Eastman had to cook for boarders to support her children’s education.

At that time, young George was a diligent student but did not excel in any particular subject. He was a decent baseball player and created intricate toys from leftover wooden sticks. Many classmates asked for toys, but he refused to give them away for free, telling them: “If you like it, why not buy it? It only costs ten cents!” And George successfully sold his “products.” He recorded his earnings in a notebook, indicating his inclination towards commerce, and throughout his life, George focused on financial matters.

When George turned 14, the Eastman family fell into dire poverty. Understanding his mother’s struggles, he decided to drop out of school to help support the family. He sought a clerk position at an insurance office, earning $3 a week. He worked diligently and responsibly. After finishing at the office, he walked several miles to help with household chores for another 6 or 7 hours. This clerical job lasted for a year until George secured a position at another insurance company’s office. Thanks to his creativity, he was assigned more important tasks, and his salary increased to $5 a week.

|

|

Edison and George Eastman |

In 1874, after five years of working at the insurance company, George Eastman was hired as a secretary at Rochester Savings Bank with an annual salary of $800. As life became more comfortable, George thought about leisure activities. He learned German and French, joined sports clubs, and occasionally rented a horse-drawn carriage to invite some girls for outings.

At the age of 24, after a period of hard work, George decided to take a summer vacation to recharge. After reading articles about Santo Domingo, he planned to visit this place. Since it was his first vacation, George carefully discussed the trip with his colleagues. When he mentioned the places he would visit, a friend expressed his desire: “I wish I could go with you! But even if I can’t, just seeing the pictures you take would be enough to bring me joy.” This unexpected comment led George Eastman into the field of photography. Although he hadn’t planned to take a camera on the trip, he considered his friend’s suggestion a good idea. Therefore, he spent $94.36 to buy a complete camera set.

At that time, photography was very complex. Photographers needed to use glass plates coated with chemicals, which had to be exposed while still wet and developed immediately afterward. Hence, when cameras were sold, they also included bottles of chemicals, trays, funnels, scales, and even a tent used as a darkroom. Reflecting on those early memories, George Eastman remarked: “An amateur photographer not only needs a camera but also an entire kit, of which the camera is just a small part. I believe being a photographer requires both strength and courage, as carrying the photography equipment is like carrying a saddle.”

For personal reasons, Eastman could not travel to Santo Domingo, so he used his free time to learn about photography. Once he understood the techniques well enough, he went to Mackinac Island to photograph the natural bridge. Eastman chose a sunny day and took his camera out to use. The group of tourists saw the photographer and lined up on the bridge to get their pictures taken. They watched Eastman set up the camera, focus, adjust the lens, and hurried back and forth from the tent to the camera with wet plates. Despite the scorching sun, the eager photo subjects patiently stood still while Eastman performed all the intricate steps. After Eastman developed the photos, one person in the group asked to buy them, and Eastman replied: “These photos are not for sale because I am just an amateur photographer.” At that moment, the customer became furious: “Are you crazy? Why did you make us stand in line for half an hour in the sun while you ran around? You should have put up a sign saying you are an amateur photographer!”

2. Developing Photographic Plates.

After the holidays, when Eastman returned to the bank, he had mastered the photography techniques of that time. Due to his passion for photography, Eastman felt the need to simplify the old, complicated methods. He sought to read photography publications from England, and then he came across the groundbreaking discovery of dry plates. This method allowed photographers to take and develop films without needing to do it all on-site, reducing the exposure time from 3 to 4 seconds down to 1/25 of a second.

After the holidays, when Eastman returned to the bank, he had mastered the photography techniques of that time. Due to his passion for photography, Eastman felt the need to simplify the old, complicated methods. He sought to read photography publications from England, and then he came across the groundbreaking discovery of dry plates. This method allowed photographers to take and develop films without needing to do it all on-site, reducing the exposure time from 3 to 4 seconds down to 1/25 of a second.

Eastman followed the formulas from the British magazine to create his own photographic plates. Initially, he only intended to make dry plates for his own use, but soon he came up with the idea of mass-producing these plates for sale. He consulted numerous books to learn about experimental and production methods. During the day, he worked at the bank, and at night he was busy mixing and cooking photographic chemicals in the kitchen. He often worked until he was exhausted. Many nights, he would fall asleep on the couch in his clothes, only to wake up in the morning. The fear of poverty haunted him, especially since his family included an elderly mother and a sister who was paralyzed on one side. Eastman worked tirelessly for two reasons: his love for his elderly mother and his desire to earn money.

In April 1880, Eastman rented the third floor of a building on State Street in Rochester to produce photographic plates after applying for a patent to secure his manufacturing method. Eastman left the bank when Henry Strong, a boarder in his mother’s house and a whip manufacturer, agreed to invest $5,000 as capital, and the two established the Eastman Dry Plate Company. Initially, selling photographic products was not difficult, and despite having six employees, the Eastman Company still needed to hire additional help. However, shortly after, photographers complained that the dry plates produced by Eastman were not very sensitive, and some dealers returned defective plates due to manufacturing flaws. Faced with this situation, several investors withdrew their support. Eastman and Strong decided to travel to England, the most advanced country in photographic equipment manufacturing, hoping that the specialists there could identify the shortcomings. After returning to Rochester, Eastman improved the old methods, resulting in perfectly functioning photographic plates, ensuring no one would complain about the products anymore.

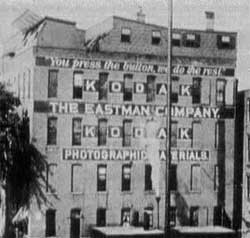

In 1884, with the thriving business of dry plate manufacturing, George Eastman was compelled to expand his workshop. He moved his headquarters to a four-story building, which today houses the iconic Kodak Tower. Aiming to simplify photography, Eastman constantly sought ways to create a material that could replace the heavy and fragile glass plates. He turned to paper, hoping to load entire rolls of film into cameras for mass photography. Alongside his research, Eastman also promoted his company. He dissolved previous contracts and established the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company with 12 associates. In 1885, Eastman advertised his product as follows: “Soon, there will be a new type of film for photography that can be used both outdoors and indoors, which is inexpensive and convenient to replace dry glass plates.”

|

|

Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company |

With the assistance of William Walker, Eastman discovered a type of photographic paper. Although this product succeeded in the market, Eastman’s invention still had drawbacks. The paper was not the perfect substrate, as images printed on it revealed the fibers of the paper. Eastman set out to find a new material to replace the paper. He experimented with collodion, but this substance did not adhere well to photographic chemicals. Consequently, he coated the paper with a soluble gelatin, followed by a layer of light-sensitive emulsion that was not water-soluble. After exposure, the emulsion layer was peeled off the paper and adhered to another clear sheet, then coated with a layer of collodion. By 1886, due to the busy organization of the company, Eastman hired additional chemists to assist with his research.

At any moment, Eastman’s mind was occupied with ideas for creating new machinery to reduce labor costs and lower product prices. After replacing glass plates with film, he noticed that the number of film users was still limited. He wanted to embark on a grand business venture and knew he had to find ways to attract the masses. He decided to provide complete photographic materials at very low prices so that everyone could take pictures. He heavily promoted his products and sought to exploit the commercial market.

To popularize photography, Eastman launched the first Kodak camera in June 1888. This was a box-style camera, small and lightweight, with a carrying strap, containing a long roll of paper film capable of taking 100 pictures. Photographers only needed to spend $25 to purchase a preloaded camera with “American Film,” and after taking their pictures, they would send the camera back to Rochester, where Eastman’s company would develop and print the images for just an additional $10.

In his advertising, Eastman stated: “You just need to press the button, and we will take care of all the rest.” This was a revolutionary approach that completely transformed commercial practices, and Eastman applied innovative methods for large-scale production to reduce costs. Thanks to this unique advertising strategy, Eastman’s Kodak camera gained worldwide fame, giving birth to popular photography.

Not only did he succeed commercially, but George Eastman also achieved remarkable technical results, notably the invention of flexible and transparent film. This film resulted from a mixture of various substances with nitrocellulose until the solution became thick enough to create a thin, transparent, and grain-free film that was durable enough to serve as a substrate for applying photographic emulsions. In August 1889, the first clear Kodak film was released to the market and received a warm welcome from photographers. This film also enabled scientist Thomas Edison to create the first motion picture film, giving rise to the film industry.

With the goal of simplifying photography, Eastman continuously researched and innovated. In 1891, Kodak produced roll film, allowing photographers to load film into their cameras outdoors, eliminating the need to send cameras back to Rochester for film loading.

With the advent of roll film, a significant change occurred. Previously, photographers had to be skilled technicians; they needed to know how to develop film and print photos, which required learning darkroom techniques. Today, with the new film, photographers only need to capture beautiful images under the right lighting conditions, as film developing and printing are handled by thousands of photo labs, both large and small.

In 1895, a collapsible pocket camera was introduced, and five years later, the Brownie camera for children was sold for just one dollar. The manufacturing of film, paper, and cameras became an industry, and Eastman Kodak emerged as the largest photographic product manufacturer in the world.

3. Contributions to the Community.

From the beginning, George Eastman aimed to discover methods to simplify photography so that the masses could benefit, and today, this has become a reality. Eastman’s contributions to the field of photography are monumental. Charles Greeley Abbot remarked, “This is a revolution in photography, achieved through the dedication of a bank clerk who pursued photography as a hobby.”

Through his creative genius, the bank clerk became a millionaire. However, despite his tremendous success, George Eastman remained humble, rarely appearing in public or having his image published in the press. Always reflecting on his humble beginnings and the struggles of survival, he devised plans to establish pension funds, insurance, and assistance for his company’s workers. Eastman was ahead of his contemporaries in demonstrating democratic and humanitarian values in building industry by sharing profits with workers proportionate to their wages, as he believed that rewarding workers fairly would lead to better products. He understood that the prosperity of an organization depended not only on inventions and patents but also on the goodwill and loyalty of its workforce. As he grew older, Eastman had to hire specialists to take over many of his research tasks, allowing him more leisure time for hunting, fishing, traveling, or enjoying music.

Through his creative genius, the bank clerk became a millionaire. However, despite his tremendous success, George Eastman remained humble, rarely appearing in public or having his image published in the press. Always reflecting on his humble beginnings and the struggles of survival, he devised plans to establish pension funds, insurance, and assistance for his company’s workers. Eastman was ahead of his contemporaries in demonstrating democratic and humanitarian values in building industry by sharing profits with workers proportionate to their wages, as he believed that rewarding workers fairly would lead to better products. He understood that the prosperity of an organization depended not only on inventions and patents but also on the goodwill and loyalty of its workforce. As he grew older, Eastman had to hire specialists to take over many of his research tasks, allowing him more leisure time for hunting, fishing, traveling, or enjoying music.

In his youth, Eastman did not receive formal music education despite his appreciation for beauty and melodious sounds. He often recounted that in his early days, he bought a flute and practiced playing the song “Annie Laurie” for two years. Although he lacked musical talent, his passion for sound art led him, in the 1920s, to draft numerous plans to establish a music school, a theater, and an orchestra in Rochester, which the citizens supported. George Eastman also contributed to hospitals and medical schools in Rochester, with a particular focus on dentistry. He financially supported the establishment of a dental hospital in his city valued at $2.5 million. When asked why he favored dental institutions, Eastman replied: “Money spent in this field yields more results than any other. In medicine, we find that children will be healthier, more vigorous, and have stronger mental capacities if their teeth, nose, throat, and mouth are well cared for when they are young.” For this solid reason, Eastman donated large sums to dental hospitals in cities such as London, Paris, Rome, Brussels, and Stockholm, and hundreds of thousands of European children have remembered George Eastman both in the past and present, as well as in the future.

In addition to supporting health initiatives, Eastman also focused on education. When the Mechanics Institute of Rochester was founded in 1887 and was struggling, Eastman donated money to the Institute and offered to be one of its ten patrons. Today, this Institute is known as the Rochester Institute of Technology.

By hiring several engineers who graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Eastman recognized their potential and grew to admire that institution. Out of respect, he anonymously donated a substantial amount of $20 million to that Institute, under the name “Mr. Smith.” There was much speculation about Mr. Smith, and in the popular song of the Institute, the current preparatory students celebrate their anonymous benefactor with the lyrics: “Hooray, hooray, in the name of the students of the Technical School and Boston, hooray, hooray for Mr. Smith, our anonymous benefactor.”

In 1924, George Eastman donated over $75 million to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.), the University of Rochester, which includes the Eastman School of Music, the School of Medicine, the School of Dentistry, the Hampton Institute, and the Tuskegee Institute, all of which support the education of African Americans. He explained his extensive charitable giving with the following reasoning: “First, the progress of the world depends on education; therefore, I chose educational institutions. I only wanted to sponsor a few fields, and I believe that with these institutions, I can find quicker and more direct results than if the money were dispersed too widely.”

George Eastman was a man who disliked self-promotion. It is quite ironic that a giant in the field of photography took fewer photographs than any other celebrity of his time. Because few people recognized him, Eastman could stroll down the main avenue of the city without being noticed. He had a great love for and knowledge of art, often visiting galleries in Europe, and he had a significant collection of paintings.

In business, Eastman was a fierce and practical competitor, and in his travels, he was also an active participant. He frequently organized large hunting expeditions in Africa, personally designing each piece of camping gear and constantly improving the equipment to be lighter, more compact, and multifunctional. He was also a skilled cook, always preparing special dishes as well as desserts.

Eastman was a brave and trusting individual. During a hunting expedition in Africa, he calmly filmed a charging rhinoceros that attacked him, while the hunter shot the beast just five steps away from him. Some were concerned that a moment’s inattention could have cost him his life, to which Eastman calmly replied: “Of course, I must trust my organization!”

George Eastman passed away in Rochester on March 14, 1932, without a wife or children. He was a pioneer in tapping into foreign markets. He also invested heavily in industrial research, flamboyant advertising methods, and marketing studies. George Eastman truly deserves to be recognized as a brilliant inventor, an extraordinary industrialist, a visionary organizer, a patriotic citizen, and a person rich in compassion and altruism.