When you look at a star in the sky, it appears as a small bright dot, and estimating its distance seems quite vague.

The question arises: How do astronomers determine their distances?

Measuring the distance from us to stars and galaxies in the universe has always been a significant challenge, a difficult problem even with today’s modern instruments.

Modern astronomers have powerful tools to observe stars and galaxies; however, we still lack an optimal method to determine the distance of a star with relative accuracy.

It often requires a combination of multiple methods or the results from many measurements. Below are some commonly used methods.

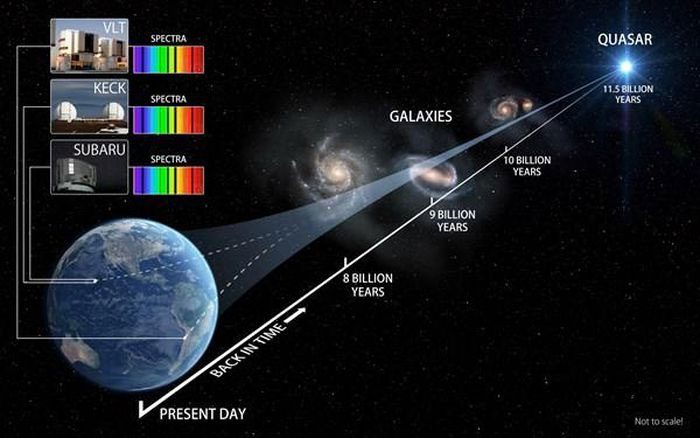

Simulation of distance measurements between Earth, the Sun, and the Milky Way.

Parallax

This method is commonly applied to nearby stars in our galaxy, which are located a few hundred to over 1,000 light-years away from the Solar System.

To understand what parallax is, try the following common method: Hold up a finger in front of your face, then close one eye and look at it with the other eye. You will notice that it appears to be in a certain position relative to the background scenery.

Next, close that eye and open the other one without changing the position of your finger. At this point, you will see that the position of your finger relative to the background has changed due to the change in your line of sight.

The phenomenon where the relative position of different objects changes due to the change in viewpoint is called parallax. This method is widely used in astronomy; the distance to celestial bodies is determined through the change in perspective with respect to them.

For the Moon and some nearby celestial bodies in the Solar System, calculating parallax is relatively simple and quick. We know that the Earth rotates around its axis in a period of 24 hours. This period is much shorter than the orbital period of the Moon around the Earth and the planets around the Sun.

Therefore, we can essentially assume that within about 12 hours (half a day), the position of these celestial bodies in orbit does not change much. The task becomes relatively easy as we only need to determine the change in perspective to the celestial body within the same day by comparing their positions against the starry background at two different times of the day.

The method of calculating the parallax determines the distance to the Moon by observing it at two different times during the day, where one of the two times has the Moon in a position directly ahead, meaning the line of sight is perpendicular to the tangent of the Earth at the observer’s position.

Since the observer’s position changes (because the Earth rotates), at the two different times, the observer sees the Moon in different positions relative to the starry background.

From this, the parallax angle is determined as the angle between the line of sight to the Moon in the initial position compared to the starry background and the line of sight at the later time. We also know the exact distance between the two observation points (the displacement due to the Earth’s rotation).

Thus, we form a right triangle where one leg and the opposite angle are known, allowing us to calculate the remaining leg using a simple trigonometric formula. The remaining leg is the relative distance from the Earth to the Moon.

This method is also applied to the planets in the Solar System, commonly referred to as the daily parallax method (since it depends on the Earth’s daily cycle).

Now, imagine pulling the Moon further away from the Earth; in that case, the parallax angle will decrease and can become so small that it cannot be measured with even the most precise instruments. For this reason, the above method cannot be applied to distant stars (the Moon is only 384,000 km away, equivalent to more than 1 light-second).

The nearest star to the Sun is over 4 light-years away. To address this situation, astronomers use a parallax method that encompasses a wider perspective, often referred to as annual parallax. Today, the distance from the Earth to the Moon and the planets at various times is well understood, so the daily parallax method is no longer necessary.

However, annual parallax, also known as stellar parallax, as described below, is still commonly used for stars that are several hundred or even over 1,000 light-years away.

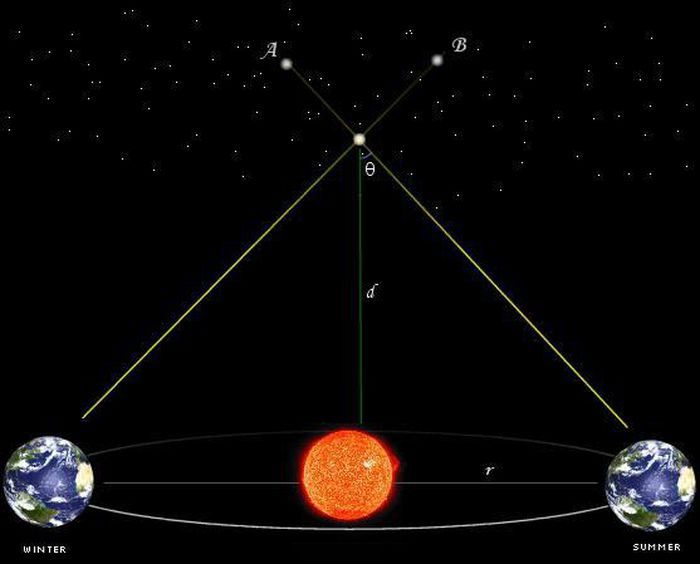

We know that, in addition to its rotation around its own axis, the Earth also has another motion: it orbits the Sun in a cycle of more than 365 days.

The average distance from the Earth to the Sun is 1 astronomical unit (au), equivalent to 149.6 million km, which means that the distance between two points on Earth opposite each other through the Sun, or the distance between two locations on Earth six months apart, is approximately 300 million km.

This distance is many times greater than the distance between two points on the Earth’s surface used in the daily parallax method. Therefore, astronomers use the change in perspective at these two positions to determine the distances of stars in the galaxy.

At the two positions of the Earth six months apart, an observer on Earth will see a nearby star in the galaxy at slightly different positions relative to the very distant starry background.

Determining the parallax angle is similar to the daily parallax method. The difference is that astronomers need to wait six months between the two measurements, and often the measurement must be continuous because even at the distance of the Earth’s orbit, the angle to the stars remains very small, even for nearby stars.

In astronomy, the parsec is used. One parsec is equal to 3.26 light-years. This is the distance corresponding to an annual parallax of one arcsecond.

This means that if a star is 3.26 light-years away, then at the two positions six months apart on Earth’s orbit around the Sun (with the condition that the line connecting the two positions is perpendicular to the line connecting the star to the Sun), the observer sees the angle of that star change compared to the very distant starry background by only one arcsecond – 1/3,600 of a degree.

This is a very small number and is often undetectable with basic angular measuring instruments.

The closest star to the Sun is about 4 light-years away, which is more than 1 parsec. This means that its parallax angle is smaller than one arcsecond. For stars farther away (tens or hundreds of light-years), this angle shrinks further, making accurate measurements very meticulous for each measurement.

This parallax method has been known for a long time, and ancient Greek astronomers also employed it. Ironically and somewhat humorously, with the primitive instruments of their time, they could not measure such small angles and believed there was no change in perspective.

This immediately became evidence for the geocentric model of that era: the Earth was the center and the distant stars were fixed on a single celestial sphere (hence the notion that there could not be a relative position change among stars).

The annual parallax method is widely applied to stars located within a few hundred light-years, sometimes even to some stars over 1,000 light-years away. However, it cannot be applied to stars at distances of thousands of light-years or to other galaxies where distances are measured in millions of light-years.

In such cases, the parallax angle becomes too small to be accurately determined by any instruments. Even if it can be measured, it cannot eliminate errors since the stars themselves have their motions, making the measurements not absolutely precise.

To measure the distance to distant stars, astronomers need to use other methods or combine multiple methods.

The distance to the Milky Way is calculated in various ways.

Spectroscopic Parallax

For distant stars or other galaxies, the parallax method based on changing perspectives cannot be used. Astronomers employ another method called spectroscopic parallax, which relies on differences obtained from the star’s spectrum to determine distance.

The Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) diagram is used to classify stars in the universe based on the color spectrum obtained from them. From the obtained color spectrum and comparing it on this diagram, one can determine which group the star belongs to and verify its absolute brightness relatively accurately.

Absolute brightness is the brightness of any star observed at a conventionally defined distance of 10 parsecs, and thus this brightness does not depend on the star’s distance from Earth.

To determine the spectroscopic parallax of a star, one compares this absolute brightness with its apparent brightness. Apparent brightness is the brightness of the star that we see each night in the sky. This brightness depends on the distance.

Stars in the galaxy have different distances from us; if two stars have the same absolute brightness, the farther star will have a lower apparent brightness. By comparing these two brightness values, astronomers can determine the distance to the star.

For galaxies other than the stars in our Milky Way, the Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) diagram cannot be used because this diagram is not intended for large groups like galaxies or galaxy clusters. In this case, the method of parallax is implemented in a different way, which is based on Cepheid variable stars.

Cepheid Variable Stars are stars located on the main sequence of the spectral diagram; they are older stars that have reached the late stages of their life cycle and exhibit significant brightness variations. Astronomers observe their brightness fluctuations within the galaxy, from maximum brightness to minimum brightness.

Their variation period provides information about the absolute brightness of the star. The comparison here is somewhat more complex than measuring the distance to a single star because astronomers need to estimate relatively accurately the total number of Cepheid stars in the galaxy and their combined brightness. Typically, this method is applied to relatively nearby galaxies, specifically to the galaxies in the Local Group.

For galaxies in more distant clusters, accurately estimating the brightness of Cepheid variable stars becomes challenging. Astronomers use another observational object, Type Ia supernovae—the explosions of stars that have reached the end of their life cycle, shattering their outer layers.

Supernovae are much brighter than Cepheid variable stars, making it significantly easier to determine their brightness when observing relatively distant galaxies.

Hubble’s Law

The final method I mention is the most common approach for measuring distances to far-off galaxies today.

In 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered the recession of galaxies through their redshift in the spectrum. This discovery led to the conclusion that we live in an expanding universe, accompanied by Hubble’s Law regarding the velocity of galaxies moving away from us.

The formula of this law is as follows: v = H × r, where v is the velocity of the galaxy moving away, H is the Hubble constant, and r is the current distance to the galaxy.

The Hubble constant has been relatively accurately determined so far because it yields a calculated age of the universe that closely matches the results obtained from observing the cosmic microwave background radiation. The velocity v can be calculated by monitoring the redshift of the galaxy. From there, one can immediately calculate the distance r of the observed galaxy.

The method using Hubble’s Law is widely applied in measuring distances to distant galaxies. However, it is not applied in cases utilizing the parallax and spectral methods mentioned above because stars in our own galaxy do not exhibit recession motion according to Hubble’s Law, while galaxies that are too close have small redshifts, making accurate determination difficult.