Treatment methods for both physical and mental ailments with a spiritual twist during the Medieval period seem to yield surprising results, according to Binghamton News.

Initially, to cure an illness, the patient required a dead vulture. However, this vulture had to be killed with a reed, and while doing so, the killer must recite a prayer. Next, the vulture’s parts needed to be properly preserved for use in healing and therapy.

The Incomplete History of Medicine

This is considered one of the therapeutic methods in the Carolingian Empire of the ninth century, an early Medieval period. This empire controlled a vast territory, which today includes France, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and northern Italy.

The healing practices of that time were nothing like the way doctors operate today in a modern clinic. Instead, healing and therapy, both physical and mental, were regarded as a sacred art.

Leja, the author of *Embodying the Soul: Medicine and Religion in Carolingian Europe*, notes that if you look at most courses on the history of medicine in universities, their content largely begins from the 16th-17th centuries, with very few books exploring the medical treatment practices of earlier periods. Medieval medicine was considered superstitious, influenced by the spiritual healing traditions of Greco-Roman culture.

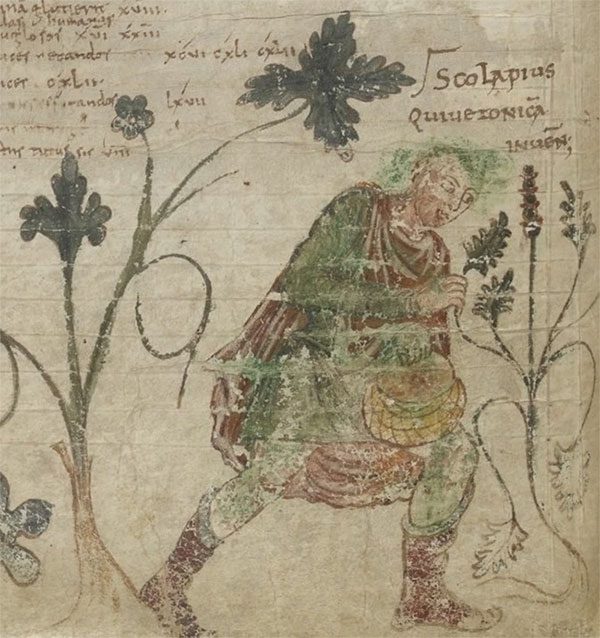

A person gathering herbs in the Medieval period. (Photo: Binghamton News).

“In the early Middle Ages, everything, including medicine, was imbued with a religious breath. However, regardless of how the practices were conducted, medicine was still recognized as a legitimate form of healing because practitioners demonstrated their understanding of how the world worked at that time,” Leja stated.

The treatments of that era often addressed some common and minor ailments such as headaches, baldness, the removal of unwanted hair, dry eyes, along with other issues. Healers in Carolus relied on theories from the Greco-Roman world concerning the four humors in the body, different fevers, and the distinctions between male and female bodies. However, actual treatment could vary slightly due to differing health conditions. There is also limited documentation on this due to many archival texts no longer existing.

Leja explains: “This was a time after the fall of the Roman Empire, and most medical works were written in Greek rather than Latin, so the entire system of knowledge became rather fragmented once it spread to other places. Carolingian scholars could only piece together small fragments of knowledge and then attempted to analyze and expand upon them. Thus, Medieval medicine was, on one hand, very classical, yet on the other hand, not entirely similar to the treatises of the medical forefathers like Hippocrates or Galen.”

Overall, treatment methods remained relatively consistent from ancient times until the 1800s: commonly practiced were venous bloodletting, along with herbal treatments, preventing infections in open wounds, and various regimes like fasting, resting, and dietary changes to prevent and treat illnesses.

Leja noted: “Sometimes, treatment recipes could involve multiple steps and include rare ingredients that might be difficult to obtain.”

Amazing Efficacy

Although the medical treatment methods of the ninth century may seem foreign to us today, they possess their own logic. In this context, words—especially those related to faith—are believed to hold a special power. Moreover, different times of day or lunar phases were thought to influence bodily fluids similarly to how the moon affects tides.

Often, people regarded these treatment factors as magical and spiritual, placing significant importance on them. As a result, in Carolus, substantial resources were dedicated to transcribing these contents onto parchment during a time when books were exceedingly expensive.

For practitioners in the ninth century, these techniques represented the pinnacle of medical science.

However, who these practitioners were remains a mystery to this day. History records only a few names of doctors from that era, such as those who worked for royal courts.

Some monks were also trained in medicine, as some monasteries allocated resources for healing. They typically established clinics, which included rooms designated for bloodletting, dispensing medications, and storing necessary pharmaceuticals.

Clerics could also be practitioners as some texts provided guidance on conducting Christian baptisms along with techniques for healing wounds. During this time, individuals known as Medicus “Doctors” emerged as spiritual figures capable of peering into the divine realm, predicting the future, and healing both the soul and body.

In a striking example of the effectiveness of this spiritual healing method, a researcher from the University of Nottingham uncovered an ancient formula for treating eye infections written in Old English. When a group of microbiologists followed the formula to the letter, including seemingly bizarre instructions for modern eyes, they produced an ointment effective against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Leja remarked: “The results of their research indicate that some treatments from that time were indeed effective, and modern individuals should not dismiss them lightly. If we only consider these formulas as superstitions or ignorance, we may be overlooking important knowledge.”