Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was a genius and an outstanding scientist in the history of human development. He made significant contributions to the field of physics, particularly with the general theory of relativity, which is considered one of the two pillars of modern physics.

>>> Genius Einstein – “The Lone Wolf”

Albert Einstein was born in 1879 in the Kingdom of Württemberg, part of the German Empire. After spending his childhood in Munich, his family moved to Italy in the mid-1890s. Throughout his school years, Einstein excelled in many subjects, including mathematics and physics. He even taught himself algebra and Euclidean geometry in just one summer at the age of 12. Besides mathematics and physics, Einstein had a keen interest in philosophy. At the age of 13, he chose Immanuel Kant as his favorite philosopher, despite Kant’s writings being somewhat challenging for the average reader.

In 1901, Einstein secured a job at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. He evaluated patent applications for a variety of electrical devices. This experience provided him with a better understanding of how electricity works. The evaluation process allowed him to examine the transmission of electricity and the synchronization between electrical and mechanical systems, which later influenced his theories about light, time, and space.

By 1908, Einstein was appointed as a lecturer at the University of Bern and later became a professor of theoretical physics there. This position helped him achieve greater success in Europe, including roles at the Prussian Academy of Sciences, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, the German Physical Society, and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1922, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the photoelectric effect. In the 1930s, he developed the general theory of relativity and demonstrated the effect of gravitational lensing.

Albert Einstein is the author of the world’s most famous equation, which describes the relationship between mass and energy: E=mc². He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his research that revealed the photoelectric effect, marking a milestone in the birth of quantum theory of light. Additionally, he made substantial contributions that laid a solid foundation for various other scientific fields, especially astrophysics. He also significantly influenced the development and operation of atomic energy in later years.

All his contributions stemmed from the thoughts and ideas that continuously flowed from an extraordinary brain: a genius mind that few can compare to. The stories surrounding his life and research remain a topic of interest for scientists who seek to understand and explore. Many researchers have sought to explain what caused such an exceptional brain. Of course, numerous scientists attempted to study his brain after his death. However, these remain mysteries that have yet to be satisfactorily answered.

Photo of Einstein 13 months before his death

Einstein passed away on April 18, 1955, after suffering an aortic rupture near his heart. He requested cremation and for his ashes to be scattered in a secret location. He did not want his remains to attract further attention or become an object of study. However, Einstein’s wishes were not fulfilled. Thomas Harvey, the pathologist who handled his body, went against Einstein’s wishes and removed his brain for research.

This marked the beginning of the adventure for pathologist Thomas Harvey and his colleagues, who carried Einstein’s brain across various regions to uncover the mysteries hidden within that extraordinary organ. The process would receive assistance from two female neuroscientists, Dr. Diamond and Dr. Witelson. Would the mystery ultimately be revealed? Stay tuned.

Everything began with pathologist Thomas Harvey at Princeton Hospital

In the final years of his life, Albert Einstein was aware of his medical condition and refused all medical interventions to try to save him. He had only one last wish: “I want to be cremated so that no one can come and worship me.” Einstein died on April 18, 1955, at the age of 76 due to an aneurysm that led to an aortic rupture. His final wish was fulfilled: his body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in a secret location that would never be disclosed. However, the matter of his brain was entirely different.

Einstein’s final moments in his hospital bed

During the autopsy performed at Princeton Hospital, a pathologist named Thomas Harvey removed and preserved Einstein’s brain—the brain that revolutionized physics with the equation E=mc², the theory of relativity, the understanding of the speed of light, and even the concept of atomic bombs. Dr. Harvey kept Einstein’s genius brain for himself.

A variety of opinions arose once people learned of Harvey’s actions. Some argued that this was merely an extraordinary scientific study, while others asserted that it was a violation of the deceased’s body and akin to grave robbing.

During his lifetime, Einstein participated in various studies to determine what, if anything, was different about his brain compared to ordinary individuals. Some even claimed that Einstein had intended to donate his brain for research purposes after his death. Others argued that Einstein never wanted to donate any part of his body and that Harvey’s act of taking his brain was indeed a serious offense.

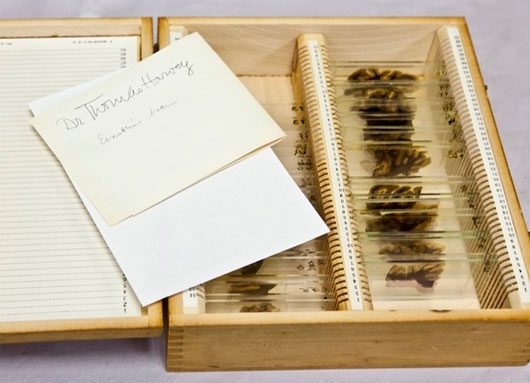

The box containing 42 pieces of Einstein’s brain in Philadelphia in 2011

In some respects, Einstein’s wishes were partially fulfilled: his body was cremated, and no one could worship his brain, as only Harvey knew where it was kept. After calming the public’s reaction to his actions, and with the permission of Einstein’s son, he began conducting research on Einstein’s brain, with the condition that the research results would be published in reputable scientific journals.

Initially, Harvey thought that it would not take long to thoroughly investigate Einstein’s brain and the differences compared to normal brains. He believed that a genius brain would be vastly different from that of an average person. However, after four years of research following Einstein’s death, Harvey had no results to show for his efforts. Eventually, he disappeared along with the brain. Some speculated that Harvey lacked the expertise to conduct the research, as he was merely a pathologist and not a neuroscientist.

Dr. Marian Diamond’s efforts regarding Albert Einstein’s brain. Could glial cells be the key?

According to reports, when Albert Einstein was born, his mother was surprised to see that her son had a head of large size and distinct contours. However, upon his death, Einstein’s brain size was not larger compared to others of the same age. During the autopsy, Dr. Harvey determined that Einstein’s brain weighed 1.22 kilograms. He took photographs of the brain and then cut it into 240 pieces, preserving them in Celloidin, a common chemical used in brain preservation and research.

Dr. Marian Diamond, who explains the differences in Einstein’s brain based on glial cells

Harvey wanted to send small samples of Einstein’s brain to scientists around the world to conduct research alongside him. The participating experts would send their research results back to Harvey and would be widely published so that the world could learn about the mysteries within a genius brain.

After that came a long period of waiting for both Harvey and the world. Einstein’s brain was of normal size, with an average number of brain cells similar to many others. Nevertheless, Harvey remained steadfast in his belief that someone would eventually discover something significant. Whenever asked about the research results, Harvey would respond that in one year or more, something would definitely be uncovered. At that time, it was reported that Harvey was living in Kansas and Einstein’s brain was stored in a jar inside a beer cooler.

In 1985, Harvey finally had something to report to the scientific community. Dr. Marian Diamond from the University of California, Berkeley, was conducting research on the plasticity of mouse brains. Dr. Diamond’s research demonstrated that mice living in enriched environments had more robust brains. Specifically, these mice had more glial cells associated with the neurons. Diamond realized that the results could be applied to study Einstein’s brain.

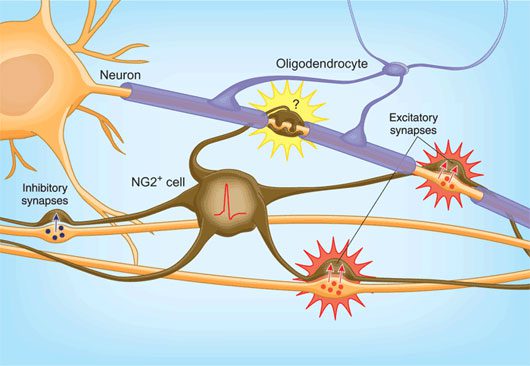

Image depicting glial cells

Glial cells serve as support and provide nutrients for neurons to function, facilitating communication between brain cells. In some cases, glial cells also perform a housekeeping function for neurons. When neurons communicate, they produce waste in the form of potassium ions. These potassium ions accumulate outside the neurons.

If the waste becomes excessive, it can affect the communication capability of the neurons, necessitating a mechanism for its removal. Glial cells perform the cleaning function for neurons to ensure they remain clean and operate at optimal levels. Additionally, glial cells help keep the pathways between neurons clear, ensuring that communication lines between neurons do not become congested.

When Dr. Diamond received a sample of Einstein’s brain for research, she compared it to a group of 11 other brain samples. Diamond reported that Einstein’s brain had a higher ratio of glial cells compared to other brains. She hypothesized that the number of glial cells in Einstein’s brain increased to accommodate the high metabolic needs of his neurons. In other words, Einstein required more glial cells to clear the waste generated during his continuous thinking processes.

Unfortunately, other scientists argued that Dr. Diamond’s conclusions were unfounded and not widely accepted. Furthermore, glial cells continuously divide throughout a person’s life. Although Einstein passed away at the age of 76, Diamond compared his brain sample to those of individuals with an average age of 64. Thus, it was natural for Einstein to have a greater number of glial cells than younger individuals. Additionally, the brain samples collected by Diamond originated from patients at the VA hospital.

While Diamond reported that the patients died from causes unrelated to neurological issues, the personal histories of these patients were not thoroughly examined, particularly their IQ scores. Another scientist pointed out that Dr. Diamond’s measuring method was just one of 28 ways to quantify cell counts. Diamond also admitted that she had not accounted for the universality in her research.

Scientists assert that the larger the number of individuals studied and the more methods applied (large sample sizes), the greater the accuracy in agreeing or disagreeing with a particular trait (statistical significance in scientific research).

At this point, things that seemed clear fell back into mystery. Would scientists give up? Did researcher Thomas Harvey find anything new? Let’s explore below.

Mystery Solved? What Did Dr. Sandra Witelson Discover?

Dr. Diamond was unable to defend her research due to shortcomings in the execution. In 1996, a researcher at the University of Alabama, Britt Anderson, published another study on Einstein’s brain with a more thorough methodology. Anderson discovered that Einstein’s frontal cortex was thinner than average but had a denser arrangement of neurons.

Anderson reported her findings to Thomas Harvey, who was then a researcher at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. During her research, Harvey discovered differences in neuron density in the cortex between males and females. He found that male brains are generally larger, while female brains have neurons that are more closely packed. This explains why females may communicate faster than males.

Harvey faxed Dr. Sandra Witelson, who was also conducting research at McMaster University. The message contained just one line: “Are you willing to collaborate with me to study Albert Einstein’s brain?” Dr. Witelson is a renowned researcher known for her work related to the brain, including IQ scores and factors affecting cognitive and psychological health. Witelson agreed to collaborate on the study of Einstein’s brain.

Neuroscientist Dr. Sandra Witelson, who hypothesized the uniqueness of Einstein’s brain based on differences in the Sylvian fissure

Witelson’s study was conducted under better conditions than Dr. Diamond’s, as by that time, scientists’ understanding of the brain had advanced significantly, with a rich database of IQ scores. Witelson used 35 male brains with an average IQ of 116 and 56 female brains as a comparison group for Einstein’s brain. This sample size was ample to draw scientific conclusions. Dr. Witelson, along with doctors and nurses, collected these samples over many years to have enough data for her research. This was the largest study in this field.

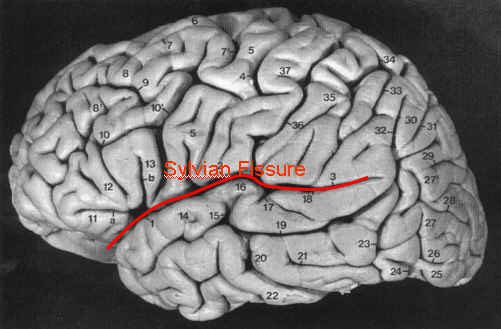

Harvey had moved to Canada, and Dr. Witelson was allowed to use one-fifth of Einstein’s brain for her research, more than any scientist before her. She chose the areas of the temporal lobe and parietal lobe, using photographs taken by Harvey right after Einstein’s death to assist her study. Witelson found that the Sylvian fissure in Einstein’s brain was almost non-existent. The Sylvian fissure separates the parietal lobe of the brain into two distinct sections, and its absence made Einstein’s parietal lobe 15 percent wider than average.

According to scientific research, the parietal lobe is responsible for processing mathematical skills, spatial reasoning, and three-dimensional shapes. This aligns perfectly with Einstein’s fields of expertise and his accomplishments. It also explains Einstein’s unique thoughts and imaginations that later became his discoveries. During the development of the general theory of relativity, Einstein imagined himself riding on a beam of light traveling through the universe. From these imaginative images, he sought words to express his thoughts, leading to the emergence of the theory of relativity.

Image of the Sylvian fissure in the human brain

Dr. Witelson hypothesized that the absence of the Sylvian fissure allowed neurons to grow closer together, thus enabling faster communication than normal. This brain structure also explained Einstein’s stuttering as well as that of others. If Einstein had known his brain was different from others, would he have continued his education?

At that time, scientists did not yet understand how the brain worked, which made it impossible to verify the accuracy of Dr. Witelson’s research. Although it was theoretically correct, the external appearance of Einstein’s brain might have seemed normal. However, with a slight variation, it could have been the manifestation of a truly genius mind. Nonetheless, scientists have not been able to absolutely verify this hypothesis, as they have yet to find a brain similar to Einstein’s, from a person with an IQ comparable to his. All research and hypotheses have only been based on average brains.

Conclusion: Back to Where It All Began. The Mystery Awaits Further Scientific Exploration

Harvey never gave up his belief that one day, the brain would reveal the hidden truths within. In the later years of his life, after traveling through many different countries, he returned to where it all began: Princeton Hospital. He entrusted Einstein’s brain to an old colleague, writer Michael Paterniti, who had accompanied Harvey and the brain through various nations. Paterniti wrote a book titled “Driving With Mr. Albert.” This book serves as a memoir of Harvey, recounting the story of the journeys of the pathologist in search of answers to his questions.

Thomas Harvey and Einstein’s Brain

Ultimately, Harvey never had the opportunity to witness the secrets behind Einstein’s brain being unlocked. He passed away in 2007 at the age of 94. And in the end, both Einstein and the mysteries surrounding his brain remain. We continue to await future scientists’ research to unravel this enigma. Hopefully, with the advancements in science and technology today, we will find answers in the not-so-distant future.