Before humans first set foot on the Moon, Johannes Hevelius published a detailed map of the Moon down to every crater.

Before humans first set foot on the Moon, Johannes Hevelius (1611 – 1687) published a detailed map of the Moon that included every crater. With only a homemade telescope, he explored and left a treasure trove of knowledge that future generations would forever admire.

A Passion for Astronomy

Astronomer Johannes Hevelius in Gdańsk, Poland. (Photo: Smithsonianmag.com).

Hevelius was born in Danzig, the Kingdom of Poland (now the port city of Gdańsk). His family was in the brewing business, so his father hoped that his son would grow up to be a businessman, gain economic strength, enter politics, and ultimately become mayor.

In accordance with his father’s wishes, Hevelius worked hard, preparing to be a skilled manager of the family business. In 1635, at the age of 24, he married a wealthy neighbor, Katharine Rebeschke. By 1636, Hevelius had joined the brewing association, and by 1643 he had become its leader. From 1651 until his passing, Hevelius served continuously as a member of the town council.

However, Hevelius’s true passion was never business or politics. Since his school days, when a teacher named Peter Krüger introduced him to astronomy, Hevelius yearned to dedicate his life to studying the stars.

To satisfy his desire for astronomical exploration, in 1641, Hevelius invested almost all his income from the family brewing company into building an observatory atop three adjacent houses he owned in Danzig.

He personally designed complex observational instruments, named his observatory “The Castle of Stars”, and turned it into one of the greatest astronomical observatories in Europe at the time. “The Castle of Stars” gained fame, attracting astronomers who predicted the return of Halley’s Comet – Edmond Halley (1656 – 1742) – who traveled hundreds of miles just to visit.

During Hevelius’s time, tides were a major concern. Not only in Poland but also in many other coastal countries, people believed the Moon was responsible for the tides and understood that knowing the Moon was the shortest path to finding a method for measuring longitude at sea.

From the outset, Hevelius’s astronomical goal was to map the Moon. After many nights observing the Moon through his homemade telescope, Hevelius produced several sketches and preliminary engravings. In Paris, the hub of astronomical research in France, Hevelius had a friend and fellow countryman interested in mapping the Moon named Peter Gassendi (1592 – 1655). Hevelius sent his initial sketches to Gassendi, who enthusiastically encouraged him to continue.

“Heaven has gifted you with eyes so exceptional they must be praised as the eyes of a lynx,” Gassendi wrote in his letter back to Hevelius. This compliment inspired Hevelius to continue his late-night observations of the Moon, whereupon he would engrave what he had seen. Finally, after five years, Hevelius completed his lunar mapping project, releasing Selenography, or A Description of The Moon, which astonished the world.

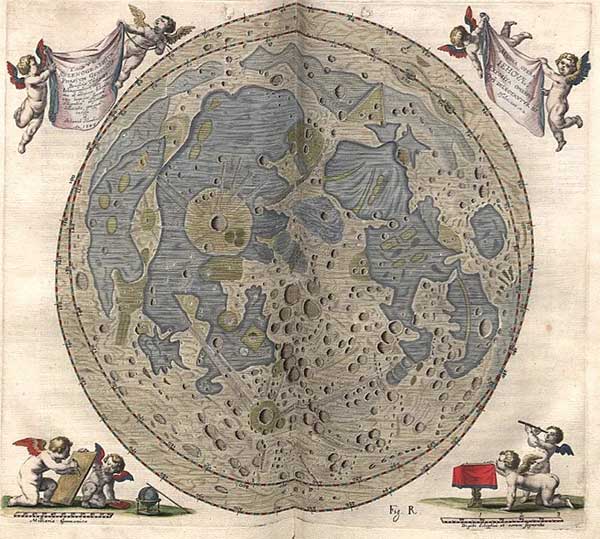

A page from Hevelius’s lunar map. (Photo: Smithsonianmag.com)

The Lunar Map

Before Hevelius, two astronomers had mapped the Moon: Thomas Harriot (1560 – 1621, England) and Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642, Italy). However, their maps were quite rudimentary. In contrast, Selenography, or A Description of The Moon by Hevelius is extremely detailed and aesthetically pleasing. It includes about 40 illustrations, each page depicting the Moon at a different phase of its cycle.

Hevelius nearly accurately rendered the Moon’s surface, complete with all its craters, slopes, valleys, and varying degrees of darkness over the days… Those knowledgeable about the Moon could recognize which day his illustrations represented. Additionally, Hevelius also observed Saturn, Mars, and Jupiter – three stars he believed to be “fixed stars” and included them in his drawings.

Each page in Selenography, or A Description of The Moon is a double-page spread, with the Moon occupying both pages. All the terrains were named by Hevelius, but due to their overwhelming number, they became quite chaotic and were not accepted by the astronomical community.

“Hevelius’s system for naming lunar terrains was too complex, as he classified them based on comparisons with Earth. Thus, they ranged from continents to islands, bays, rocks, and swamps…”, later astronomers explained.

Nonetheless, the accuracy and aesthetics of Selenography, or A Description of The Moon cannot be criticized. For the next century, it remained the most reliable lunar map.

After Selenography, or A Description of The Moon, Hevelius also compiled a catalog of over 1,500 stars with clear positions and distances. This time, he did not work alone but was aided by Elisabeth Koopman, his second wife, who was 35 years younger than him.

His passion for astronomy was what brought Elisabeth to Hevelius. Unfortunately, on September 26, 1679, while the couple was away from home, The Castle of Stars was engulfed in a fire. From the observatory to notes, all manuscripts were reduced to ashes.

Fortunately for Hevelius, his daughter had previously taken the catalog of over 1,500 stars to store elsewhere. Surviving the Siege of Danzig in 1734 and even the bombings of World War II, this catalog reemerged in 1971, akin to “a phoenix rising from the ashes,” unexpectedly appearing at Brigham Young University.

| Today, with the most advanced measurement technology, humanity has created 3D maps of the Moon, the universe… and of course, we have confirmed distances between stars with near accuracy. Interestingly, even with just the naked eye and homemade astronomical tools, Hevelius estimated distances that do not differ much from current measurements. |