In the history of human knowledge, few minds have achieved accomplishments like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. He was not only a great philosopher but also a mathematician who laid the groundwork for calculus.

The Controversy Over the “Father” of Calculus

Leibniz was born in Leipzig in 1646 into one of the most prestigious families in Europe. His father, Friedrich Leibniz, was a professor of Law and Philosophy at the University of Leipzig. His father passed away when he was only six years old, and throughout his education, he was fortunate to inherit his father’s extensive library.

Receiving a modern education influenced by the thoughts of Descartes and Galileo, alongside the traditional ideas of ancient philosophy, he sought to integrate scholastic philosophy with modern scientific methods throughout his career.

After obtaining his bachelor’s degree from Leipzig, he continued his education at Altdorf, where he received a doctorate in Law in 1667.

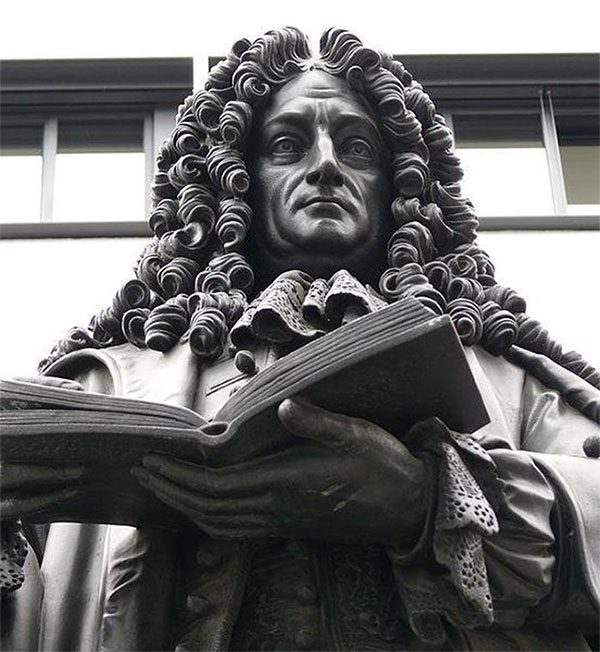

Statue of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in Leipzig.

His career took a significant turn in 1672 when Leibniz was given an important diplomatic mission to Paris, the center of science and education in Europe. After spending four years in Paris and London, he met many prominent intellectuals of the time, including Antoine Arnauld and Nicholas Malebranche.

Among them, the most important to him was the mathematician Christiaan Huygens, who guided him and shared the latest scientific discoveries. As a result, Leibniz not only engaged in discussions with some of the brightest minds of the 17th century but also accessed unpublished manuscripts of Descartes and Pascal—the two scholars who had the most significant impact on his development.

This intellectual life came to an abrupt end when Leibniz’s patron died. He was forced to move to Hanover to work as a librarian. On his way to Hanover, he stopped in Amsterdam to meet Spinoza in 1676. They discussed Ethics, Physics, and Mathematics. Although Leibniz would visit Italy again in the 1680s to study history, he spent most of the rest of his life in Germany.

Leibniz held various positions in the court, first serving Johann Friedrich until his death in 1680, then Ernst August (from 1680 to 1698), and finally for his son, Georg Ludwig, who would become King of Great Britain in 1714.

Despite feeling isolated from the European intellectual scene at the time, Leibniz worked to maintain connections through an extensive correspondence network. He exchanged letters with over 1,100 individuals throughout his life. He began as a librarian, later becoming a historian and a member of the secret council at the court. Despite the tremendous challenges faced by Leibniz, he managed to complete an astonishing volume of work given the depth and breadth of his knowledge.

Leibniz’s later years were marked by gloom. He became embroiled in a fierce debate with Newton over the invention of calculus. He was even accused of stealing ideas.

Most historians today affirm that Newton and Leibniz developed their ideas on calculus independently. Newton conceived the initial ideas, while Leibniz was the first to publish his research. Leibniz passed away on November 14, 1716.

Leibniz’s Philosophy

Leibniz received a traditional education in scholasticism and Renaissance humanism; his foundations were rooted in Aristotle, Plato, and Catholicism. However, as he became more familiar with the modern scientific thoughts of the 17th century, he recognized many advantages of this scientific approach.

Yet, he remained cautious about certain aspects of modern science. These concerns led him back to Plato, Aristotle, and Catholicism. Therefore, it may be most useful to view Leibniz’s thoughts as a response to two sets of modern opponents: one being Descartes, the other Hobbes and Spinoza.

Leibniz’s critique of Descartes primarily focused on Descartes’ interpretation of physical objects. According to Descartes, the essence of objects is that they occupy space; an object is simply something that has size and shape and is moving in space. Indeed, this view formed the foundation of the science that initially attracted him. However, Leibniz identified two problems with this perspective.

First, by asserting that the essence of an object is to occupy space, Descartes endorses the view that matter can be divided infinitely. But if matter can be infinitely divided, a physical body cannot exist as a separate entity and therefore cannot interact with the mind.

Second, if the essence of matter is merely to occupy space, then objects lack a source of activity. Objects would only interact and collide based on physical laws and would not be able to act on their own.

Hobbes and Spinoza, despite their individual differences in thought, presented several problematic arguments that Leibniz (and his contemporaries) considered a significant threat: materialism, atheism, and determinism.

Perhaps Leibniz’s greatest concern was the deterministic philosophy of Hobbes and Spinoza. Thus, he sought to develop a theory that allowed for self-activity and randomness to preserve human freedom. Therefore, for Leibniz, God freely chose the best of all possible worlds for us.

Leibniz made significant contributions across various fields, from Philosophy to Mathematics and beyond. His unwavering pursuit of harmony, freedom, and goodness continues to shape our thoughts today.

|

Famous Quotes by Leibniz

|