Frances Glessner Lee elevated forensic science in crime investigation to new heights by recreating crime scenes of violent cases. Not only that, she also became the first female police captain in the United States.

Frances Glessner Lee elevated forensic science in crime investigation to new heights by recreating crime scenes of violent cases. Not only that, she also became the first female police captain in the United States.

When Passion is Limited by the Era

Frances Glessner Lee (1878-1962), known as the “Godmother of Forensic Science”, was born into a wealthy family in Chicago and thus inherited a vast fortune from her parents.

From a young age, Lee and her brother were taught at home by tutors. As they grew up, Lee aspired to study medicine. However, her father did not allow his daughter to pursue higher education, as at that time, “a lady did not attend school” was the prevailing belief.

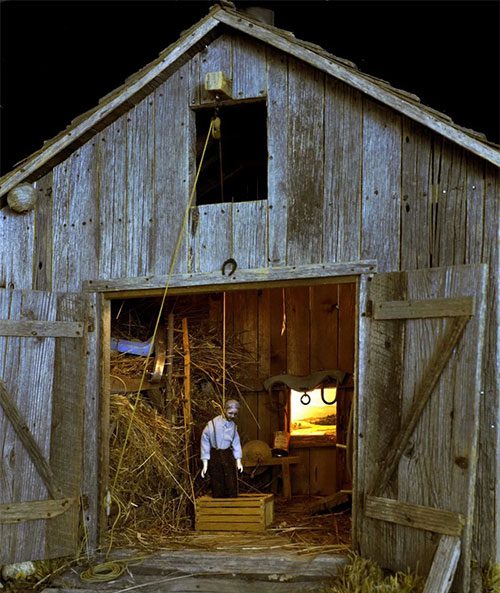

Frances Glessner Lee studying crime scene models in the early 1940s.

At the age of 19, Lee married a lawyer, and they had three children together, but the marriage ultimately ended in divorce after many years. In the 1930s, after her divorce and at the age of 50, Lee inherited her family’s wealth.

The Journey to Pursue a Dream

As a young girl, Lee was captivated by stories of Sherlock Holmes. However, it was her brother’s classmate at Harvard, George Burgess Magrath, who truly ignited her passion for crime scene investigation and forensics.

Magrath, who was studying medicine at the time, often shared stories with Lee about real-life crimes he had helped solve. This sparked her passion for science, specifically forensic medicine. Magrath later became a professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and the chief medical examiner in Boston.

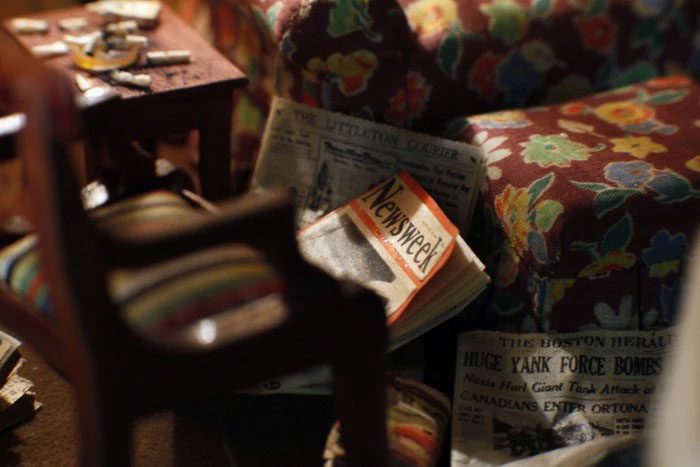

The meticulous details in Frances Glessner Lee’s works.

In the biography Death in Diorama about Frances Glessner Lee, it is noted: “Through her friendship with Magrath, she learned about the challenges of investigating the causes of violent death.” In reality, investigators often do not need a medical degree, while police officers lack training in how to collect and preserve medical evidence. Consequently, many murderers were set free due to this oversight.

Inspired, Lee decided to pursue her passion for forensic investigation. In 1931, she donated $250,000 to establish the country’s first Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University, nominating George Magrath as its chair.

As the field of forensics at that time was male-dominated, Lee had to find ways to stand out and carve a niche for herself.

An innovative yet somewhat macabre idea came to her mind: Create miniature replicas of actual crime scenes to help detectives examine clues in horrific cases of unexplained deaths.

However, these crime scene reconstructions were not conducted on real people; instead, Lee executed them using dollhouses. Making miniature models was a popular hobby among wealthy women. Thus, Lee took what she knew and set to work.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Lee used actual police cases to recreate chilling crime scenes in miniature form. The details in Lee’s works were strikingly accurate—everything from the position of decaying corpses to the dark red blood stains on patterned wallpaper.

This series of simulation models was called The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, and Lee created a total of 19 such models. These models were later used to train investigators, helping them to “convict the guilty, exonerate the innocent, and get to the truth succinctly.”

Lee understood that to be respected, her “crime scenes” needed to be crafted meticulously and also scientifically accurate. She purchased doll heads and body parts made of porcelain, always ensuring that their shapes accurately reflected human anatomy.

Ariel O’Connor, a curator at the Smithsonian, noted: “You can’t buy a doll with rigor mortis.” In her simulations, Lee recreated cases with astonishing detail: A woman hanging in an unusual rigor mortis position—indicating she may have died before being hanged; dolls with pale colors while some body parts were a deep red—evidence suggesting whether the body had been moved.

In her work, Lee was so meticulous that she became obsessed. One of her diorama pieces, titled “Saloon and Jail,” depicted a man lying face down on the street. Debris scattered on the sidewalk included miniature cigarettes, banana peels, and crumpled papers depicting a face. The storefront behind displayed newspapers and magazines with actual covers from the date the man died. A tiny, colorful lollipop jar lay beneath the magazines, with each candy individually wrapped in cellophane. All details were crafted to an extraordinary level of precision.

Lee began working with the New Hampshire State Police. In 1943, she was appointed as the captain, becoming the first woman in the United States to hold this position.

The Legacy of the “Godmother of Forensic Science”

Through the models created by Lee, donated to Harvard in 1945, students there could learn how to effectively gather crime scenes to uncover and analyze evidence. Through their findings, they could determine whether a scene was the result of murder, suicide, natural causes, or accident.

Lee passed away in 1962 at the age of 84. A few years after her death, the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard was disbanded, and Lee’s Nutshell artworks were later transferred to the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

There, the artworks remained and continued to be used as training tools in forensic workshops, attracting over 100,000 visitors.

Additionally, her brief studies of unexplained deaths have inspired television programs such as “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.”

Lee’s legacy continues to endure to this day.