A supermassive black hole is trying to escape its galaxy due to an extremely strong gravitational force. On its path, it has left behind a trail of ionized gas and newly formed stars.

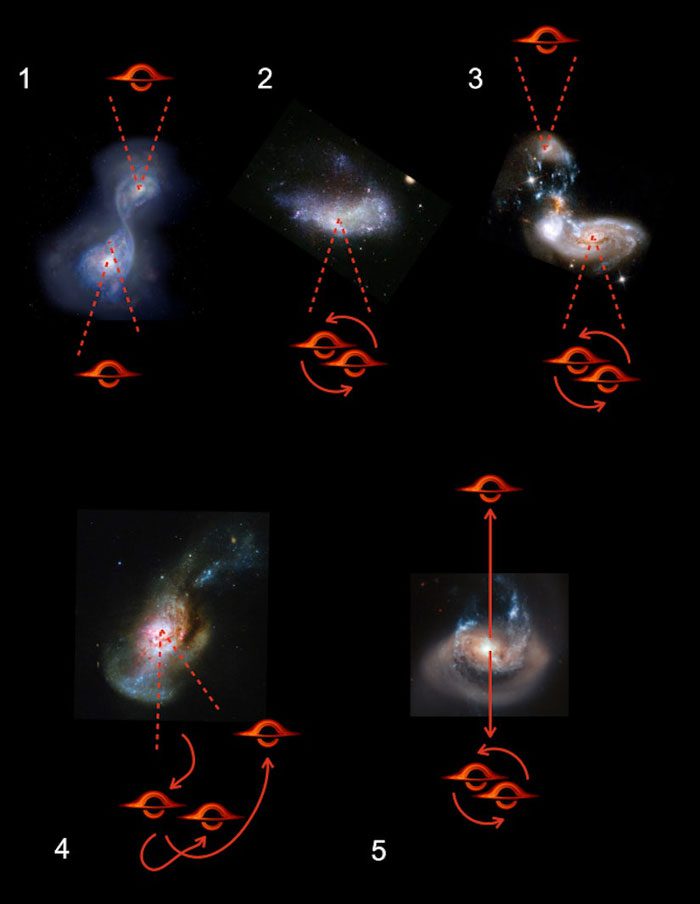

Galactic collisions and mergers are common events in the universe. Most of the larger galaxies we see today were formed through a series of galaxy mergers, and it is predicted that our own spiral galaxy will one day collide with the Andromeda Galaxy.

When galaxies merge, their supermassive black holes often merge as well; drawn together by each other’s gravity, the two supermassive black holes will eventually spiral around each other in a death spiral until they collide and become one. Simultaneously, this process sends powerful gravitational waves rippling through the universe.

However, recent computer simulations suggest that there will be some anomalous occurrences during this process, such as a supermassive black hole being ejected from its galaxy. Yale University astronomer Pieter van Dokkum and his colleagues may have found evidence of this happening in a small, oddly shaped galaxy located about 10 billion light-years away.

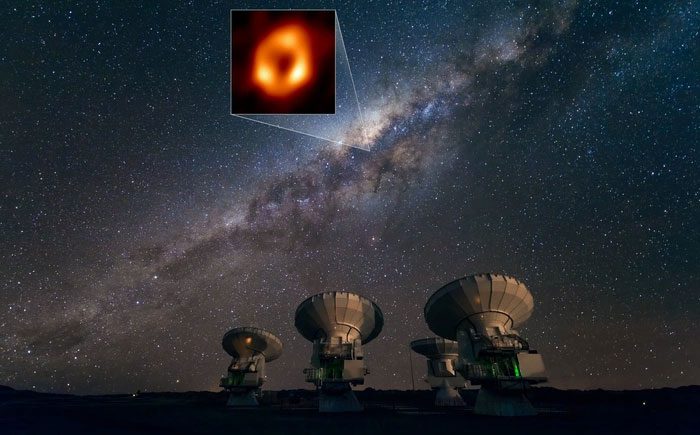

According to current research, a black hole is a region of spacetime with an extremely strong gravitational field. Therefore, unless they actively “feed” (by pulling in matter and light from the universe), humans cannot actually detect black holes, as no electromagnetic radiation can escape the overwhelming gravitational pull of this “cosmic monster.”

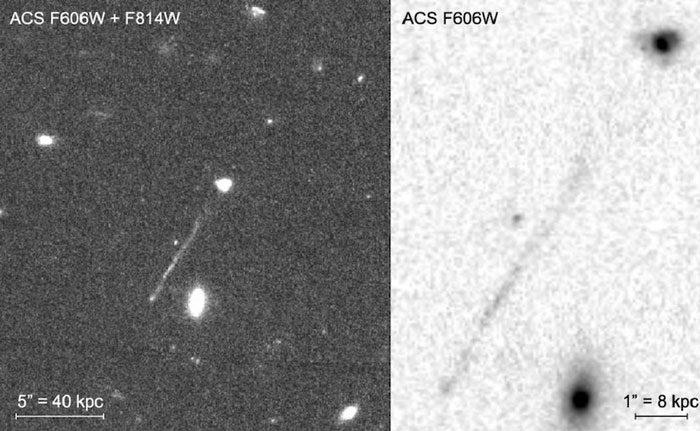

In a recent series of images from the Hubble Space Telescope, van Dokkum and his colleagues discovered a narrow trail in the small galaxy.

The galaxy has yet to be named, it is relatively small but filled with dense gas clouds brimming with new star formation. From its center, an almost straight trail—visible because it is much fainter than the rest of the galaxy—extends over 200 light-years, ending with a bright ultraviolet streak.

Along the 200-light-year trail, a series of newly formed star clusters appear, glowing with ionizing radiation. By measuring the wavelengths of light from these stars, van Dokkum and his colleagues were able to estimate their ages, with the youngest stars being the farthest from the galaxy’s center.

If a black hole is in a binary pair and actively “consuming” the other black hole, then the matter swirling around it will emit powerful X-rays and radio waves. Once this material is observed, we can understand how the black hole operates.

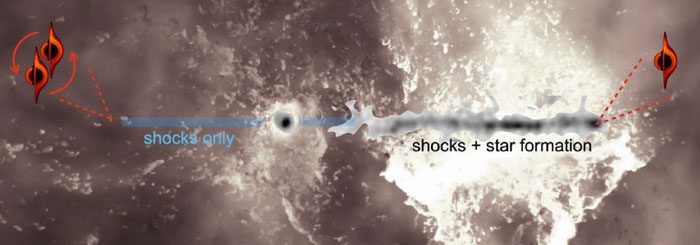

Van Dokkum and his colleagues suggest that it appears a strong shock wave has emanated from the galaxy’s core, creating a path for itself and leaving behind a trail of compressed, hot gas that triggers subsequent star formation explosions.

The most fitting explanation for the data from Hubble is that there is a supermassive black hole trying to escape. As van Dokkum and his team propose, about 39 million years ago, a galaxy merger expelled a supermassive black hole from the core of its galaxy and hurled it into space at a speed of about 360,000 miles per hour.

Scientists have long believed that supermassive black holes can move through space, but capturing this spectacle is quite challenging. Among the 10 million black holes in the Milky Way, up to 7.5 million may be ejected at extremely high speeds.

Typically, when two supermassive black holes merge, they form a larger black hole at the center of the newly formed galaxy. But occasionally, gravitational waves from the merger create a rebound force, giving a powerful kick to the new supermassive black hole, causing it to dart away from the galaxy’s core.

When this occurs, one would see an extremely heavy, incredibly dense object moving at a terrifying speed through the interstellar gas clouds, pushing a bow shockwave ahead of it and trailing a long streak of ionized hydrogen, compressed gas ripples, and star formation explosions behind it.

Van Dokkum and his colleagues think that this may be what is happening in their unnamed small galaxy.

Scientists predict that there are two possibilities for the supermassive black hole moving away from its galaxy. First, this could result from a collision and merger of two black holes, causing the new black hole to be flung backward. Additionally, this black hole may belong to a rare binary black hole system. Its “companion” has yet to be detected, possibly because it does not emit maser signals.

This idea is supported by the surprising lack of activity at the center of the small galaxy—no supermassive black hole seems to have formed there.

Van Dokkum and his colleagues write: “The morphology of the features in the Hubble Space Telescope images is so striking that it is not too difficult to find more examples if they exist.”

When the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope launches in 2027, it may help astronomers discover even more fleeing supermassive black holes in other galaxies.